My Superpower is a regular guest column on the Skiffy and Fanty blog where authors and creators tell us about one weird skill, neat trick, highly specialized cybernetic upgrade, or other superpower they have, and how it helped (or hindered!) their creative process as they built their project. Today we welcome Aidan Doyle.

My superpower is reading the air.

I taught English in Japan for 4 years and I once heard my students referring to someone who was KY. I learned this meant kuuki yomenai — literally unable to read the air. Unable to read the unspoken messages others are trying to convey. Unable to grasp the context of the situation.

My Japanese co-workers would often ask me for advice about how to phrase something in English. They pointed out to me that my answer was often “it depends.” So much depends on context. Sam Sommers’ book, Situation Matters: Understanding How Context Transforms Your World, examines this topic in more detail, especially the idea of how much of our behavior is dependent on circumstances. “We’re easily seduced by the notion of stable character. So much of who we are, how we think, and what we do is driven by the situations we’re in, yet we remain blissfully unaware of it.”

I’ve been fortunate enough to see a lot of the world (100+ countries) and one of the benefits of traveling is that it can help you understand different situations and broaden your perspective on how people behave. Learning a second language is another way to help see beyond the default context. Teaching English as a foreign language also helps you notice the quirks of the language that can be effectively invisible to native speakers. Why can you say “on the train” and “in the train”, but “in the car” and “on the car” have different meanings?

Japanese poet Sei Shōnagon was someone who excelled at reading the air. Shōnagon had to negotiate the intrigues of Heian-era Japan, where understanding context, especially as it related to poems, was all important. In the introduction to The Pillow Book, Meredith McKinney writes: “Anyone who hoped to be admired and accepted had to be deeply knowledgeable about the poetic canon, particularly the poems contained in the classic poetry collections such as Kokinshuu, and able to weave apposite allusions to them into her or his own occasional poetry. Wittily nuanced messages, generally containing a poem, flew constantly between members of the court and sometimes beyond; these in turn required a suitable extempore poem in response, written in an elegant hand on paper carefully chosen for appropriateness of color and quality, in every aspect of which one’s sensibility and character would be displayed for intense scrutiny. Although such exchanges of poetry were common throughout the court, by long tradition it was the romantic relationship that quintessentially embodied the essence of poetic exchange. A man could fall in love with a woman on the evidence of little more than her poems; a woman could decide to sever relations with a man if he demonstrated poetic obtuseness, as Sei Shōnagon several times describes herself doing in The Pillow Book.”

Murasaki Shikibu, the author of the Tale of Genji, is the other giant of Japanese literature from that time. In his book The World of the Shining Prince, Ivan Morris writes about the impact of Genji on Japanese culture. “…more than ten thousand books have been written about The Tale of Genji, not to mention innumerable essays, monographs, dissertations, and the like; in addition there are several Genji dictionaries and concordances, and hundreds of weighty works in which Murasaki’s novel has been used as material for the study of subjects like Heian court ceremony and music… No other novel in the world can have been subjected to such close scrutiny; no writer of any kind, except perhaps Shakespeare, can have had his work more voluminously discussed than Murasaki Shikibu… The role of quoted poems was recognized as particularly important in Murasaki’s imagery. While civil war raged throughout Japan, many a medieval scholar spent his years patiently ferreting out poems in obscure anthologies or private collections from which Murasaki may have derived her quotations.

As the world of The Tale of Genji receded into the distant past, the language of the novel began to present ever greater difficulties. The first Genji dictionary dates from the fourteenth century, and much of the work during the Muromachi period was devoted to linguistic interpretation. The study of manuscripts and the comparison of different versions also became important, as scholars tried to establish a definitive text of the work. By now Genji scholarship had largely become the preserve of certain aristocratic families, and we are confronted with the strange tradition of secret commentaries and secret texts, which would be handed down in particular schools like precious heirlooms. Various “Genji problems” were listed, and each school would have its own arcane interpretations, jealously guarded from other schools and imparted only to trusted disciples. A good deal of the effort of the medieval scholars was devoted to the exhilarating task of demolishing the work of rival groups.”

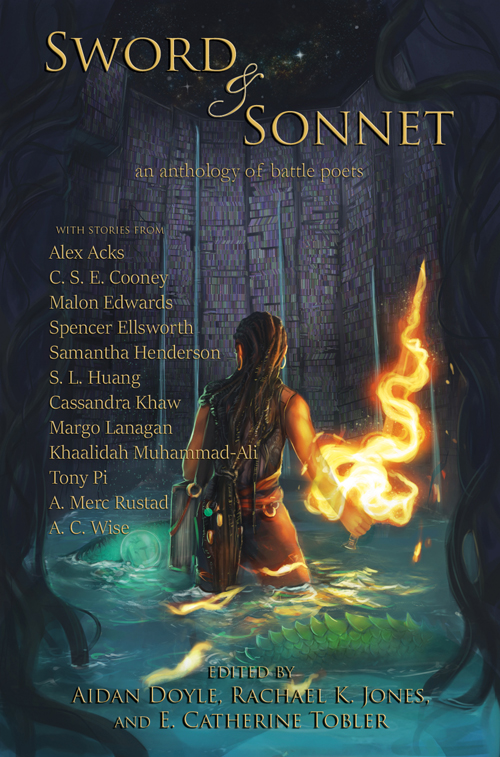

E. Catherine Tobler, Rachael K. Jones, and I are editing an anthology of genre stories about women and non-binary battle poets. Lyrical, shimmery sonnet-slingers. Grizzled, gritty poetpunks. Word nerds battling eldritch evil. Haiku-wielding heroines. Rachael was recently nominated for a World Fantasy Award for her story, The Fall Shall Further the Flight in Me, but it’s her story, “Makeisha in Time”, that I love the most.

“Makeisha has always been able to bend the fourth dimension, though no one believes her. She has been a soldier, a sheriff, a pilot, a prophet, a poet, a ninja, a nun, a conductor (of trains and symphonies), a cordwainer, a comedian, a carpetbagger, a troubadour, a queen, and a receptionist. She has shot arrows, guns, and cannons. She speaks an extinct Ethiopian dialect with a perfect accent. She knows a recipe for mead that is measured in aurochs horns, and with a katana, she is deadly.”

The story deals with the erasure of women from history, as does E. Catherine Tobler’s story, “In the Otherwise Dark.” For so much of recorded history, the context has been framed from the man’s point of view. We want to bring you an anthology full of awesome women and non-binary battle poets. The project is live on Kickstarter in November and we’d love your support.