If you missed Rosalind’s Siblings when it was published in September 2023, please consider adding it to your reading list for the new year. It’s a very interesting anthology of speculative fiction and poems, containing some fascinating ideas and characters and some really beautiful language. Edited by Bogi Takács, it features both new and established authors from around the world.

Calling it Rosalind’s Siblings is a salute to scientist Rosalind Franklin, a chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose work was fundamental to understanding DNA, along with important contributions to knowledge of viruses and coal, but as the back cover says, “her contributions were often erased.” The anthology pays tribute to her by collecting more than 20 fictional works focusing on scientists marginalized and/or exploited due to their gender.

That might sound a little depressing, and some of the pieces in the anthology are, but many of them are profoundly hopeful about overcoming obstacles and navigating toward a better future. In some of them, on the other hand, the minority populations hardly have any struggles with marginalizations, but are shown simply doing their jobs, and that, too, is hopeful.

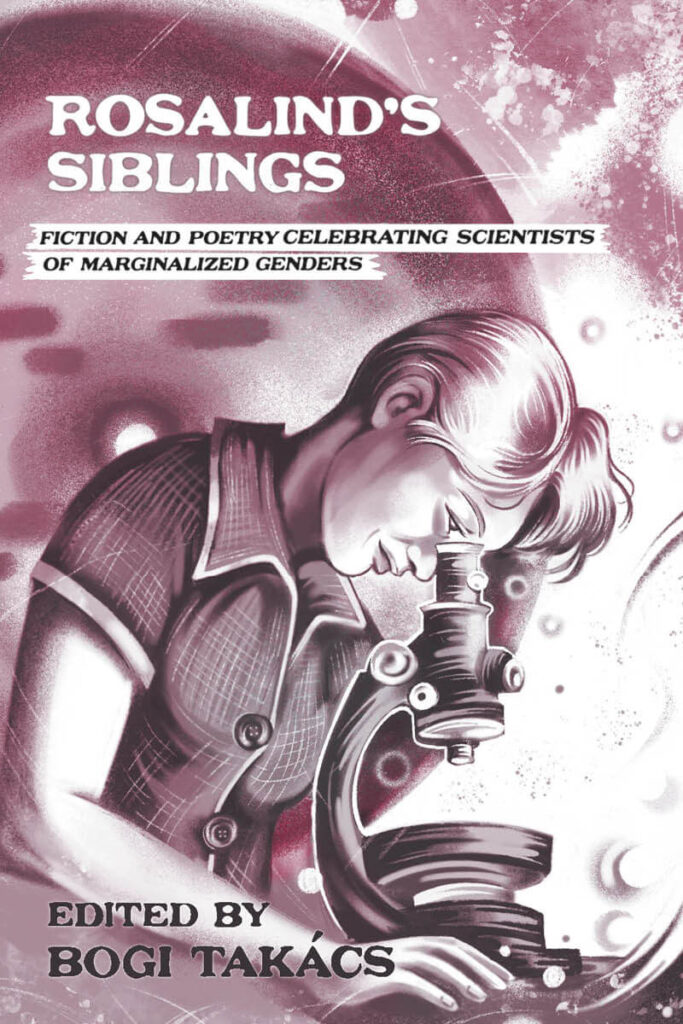

The first impression of the book is from its purple-toned cover illustration by Mia Carnevale, in which a short-haired, female-presenting person is staring through a microscope, with clouds and planetoids in the background. A slight smile quirks the lips, as though intriguing speculations are arising. It’s quite engaging.

The first piece in the collection, “Collecting Ynés” by Lisa M. Bradley, subtitled “A slightly mythologized account of the life of Ynés Mexia” (who was a Mexican-American botanist), combines poetry with prose. As Ynés ages, she eats and assimilates various plants, and eventually plants grow out of her. In the end, “Ynés lives on as the plants do: tenacious, timeless. Transubstantiation in reverse.” It’s weird, and also weirdly affecting.

I’ll admit that I had trouble connecting with a number of the poems and other very short pieces. However, one piece that really spoke to me was “The Astronomer Aspiring” by Hal Y. Zhang, a poem that compares stars extinguishing themselves to the brief lives of flowers.

One story that isn’t a poem, but employs lovely, lyrical language, is “The Starship Ariel” by Lydia Moon, about an AI originally cloned from a human mind, which encounters a lost spaceship and crew sending out distress signals.

“You’ve worn a hundred forms, each different and beautiful and elegant. A cloud of a million silver motes above Mercury, a diamond of pure mind blown by the inexhaustible winds of Jupiter, a dagger darting beneath Europa’s seas, a kite swooping from the peaks of the Martian mountains.”

The decision that this self-evolved mind makes about how to answer the distress signals may be a bit chilling, but it’s completely believable, and wondrous experiences clearly lie ahead.

Another story in which the language is important, because it seems to encourage some expectations that are then subverted, is “To Keep the Way” by Phoebe Barton. The cute names for the wildlife on this alien planet, like trilochomps and minnowlikes, led me somehow to expect a peaceful or even a funny resolution with would-be colonists. But the guardian of the planet is sternly resolute, and the resolution feels right – the adorable quirkiness of its denizens makes protection of this unique ecosphere all the more important and necessary.

One of the things I really like about this collection is how wide-ranging it is, both in styles and in subjects. Several of the stories focus on understanding the universe and making connections with it. Several focus on relationships among explorer/scientists and how those affect missions in their small, closed communities. Other obstacles besides those previously mentioned include credit-stealing bosses, self-doubts, systemic exploitations by governments and corporations, and more.

To keep this review from being too long, I’ll end by mentioning one of the more unusual stories, “Cavern of Dreams” by Julie Nováková, in which Agnieszka finally makes peace with the loss of her fellow scientist, Paul, in a cavern they’d been exploring, after an Opening had occurred that granted powers to people, and science had become less reliable. The uncertainties of dealing with that situation are shown with insight and empathy. And I love how it ends:

“Perhaps, the world still remains this vast beautiful space awaiting our curiosity.

“I smile at the stars above, content with that.”

Content Warnings: Deaths, some icky biology, mentions of offscreen sexual violence, etc.

Disclaimers: I received a free copy of this book from the publisher, Atthis Arts, whose executives are friends of mine. I’ve also done some proofreading for Atthis Arts, although I did no work on this project.