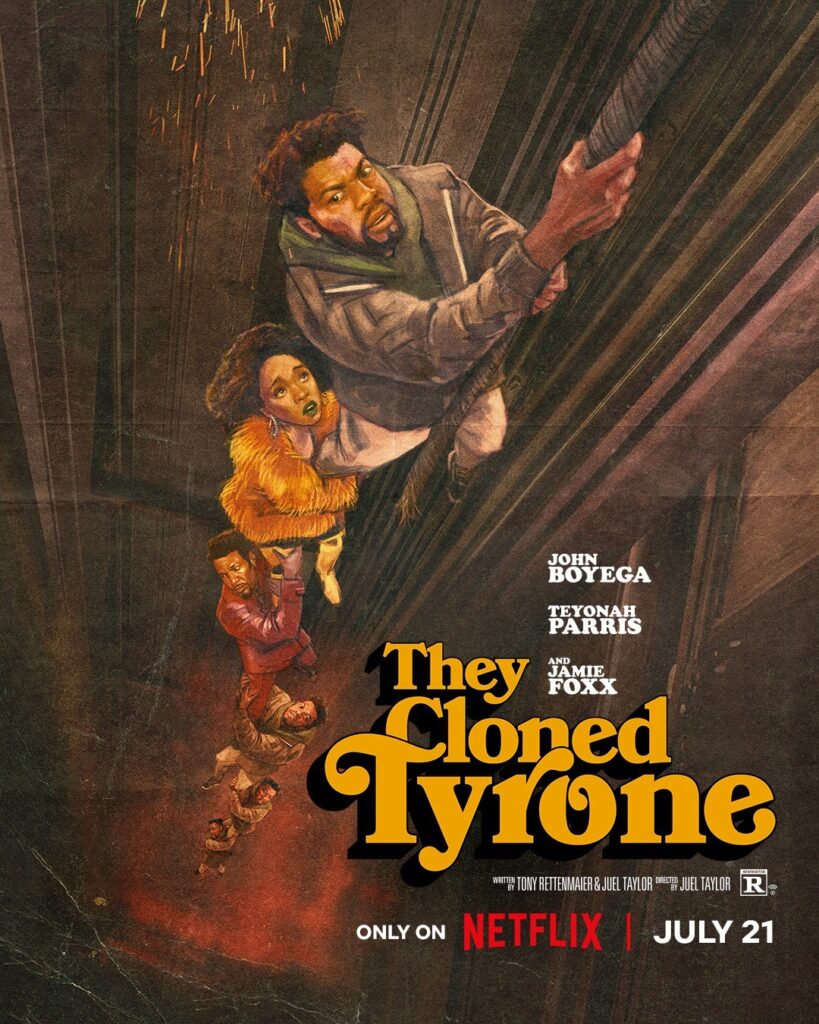

After a premiere in June at the American Black Film Festival in Miami and a brief, weeklong limited theatrical release a month later, Juel Taylor’s They Cloned Tyrone debuted on Netflix streaming. The movie has earned critical and general audience acclaim in a little over a month since, and Skiffy & Fanty followers with access to Netflix should check it out if they haven’t already.

Fontaine (John Boyega) lives a daily rhythm of detachment and survival, trapped in a listless existence of dealing drugs in the Glen: chasing down payments and dealing with rivals. Haunted by memories of his little brother who was gunned down in innocence by the police, Fontaine yearns for physical and emotional contact with his distant mother, and tries to quell the pain of his familial loss through brotherly guidance of a young neighborhood boy called Junebug (Trayce Malachi).

When one of Fontaine’s street dealers checks in with a light envelope, unable to locate a Glen pimp for scheduled payments, Fontaine goes to find the man, Slick Charles (Jamie Foxx), himself. But Fontaine’s drug king rival Isaac (J. Alphonse Nicholson) trails him, intent on exacting revenge against Fontaine for an earlier attack on one of Isaac’s street dealers. Slick Charles, along with one of his sex workers, Yo-Yo (Teyonah Parris) are there to witness the altercation between Fontaine and Isaac, and subsequently get drawn into the consequences that follow.

So events set in motion bringing together the drug dealer, the pimp, and the sex worker for discovery of a vast governmental conspiracy that envelops the entire Glen neighborhood. As the title reveals, it involves cloning. As for the identity of Tyrone, audiences will have to wait for the end credits. (The title is a nod to Erykah Badu’s song “Tyrone”, which the artist has re-recorded as “Who Cloned Tyrone” for the movie.)

Taylor crafts his debut feature with clean pacing, confident style, and consistently balanced tones between action, humor, and gravity. First envisioned as an homage to 1970s Blaxploitation films, They Cloned Tyrone achieves the vibes of that inspiration while folding in genre elements of science fiction and mystery. The science is light, the speculation is more of a social reflection, and the mystery can feel contrived. But, Taylor uses conventions of these genres as a foundation for the allegorical heart of the movie: powerful meanings that coalesce around the concept of a trap house and the circumstances of Black America.

For those unfamiliar with the lingo, a trap house is a seedy, otherwise abandoned location used for illegal drug manufacture, dealings, or use. The term arises from the concept of people becoming caught in a destructive circle of addiction and criminality as part of the drug trade. Trap houses appear at all levels in They Cloned Tyrone: in a classic literal sense, on the grander scale of the Glen as a whole, at the level of governmental conspiracy, and within the psychology of each of the characters, both protagonist and antagonist. In this way the film exists as social satire of how the systems of America serve to keep African Americans trapped in an endless racist cycle of adversity, subservience, and suffering.

The characters all face their predicament of entrapment in different, representative ways. Yo-Yo actively seeks escape, with hope and confidence that she can successfully get out of the Glen with a bit of money and establish a new, better life for herself elsewhere. Slick Charles looks upon such a view with derision, as a delusion. He masks the pains and destructive circles of his life with irreverent humor and lavish style, covering wounds with an aggrandized ego and pride that even if he is a pimp, he’s a respected, award-winning pimp. Finally, Fontaine turns from his pain with anger, frustration, violence, and utter grief. Only buoyed at moments by the youthful innocence and optimism of Sponge Bob-adoring Junebug, Fontaine has resigned himself to the drug dealer’s life as much as Slick Charles has to that of pimping.

However, the discoveries of conspiracy and personal identity propel Fontaine, with the aid of Slick Charles and Yo-Yo, to grow past his resigned, hurtful existence. Together, they find the strength to fight. Slowly they come to the realization that their success can only come from the entire community putting aside differences (including drug gang rivalries), and each person’s individual traumas, to act together as one force of resistance. A resistance against control, entrapment, and (as it’s eventually revealed) racial assimilation.

One issue with this narrative is that the growth, activism, and breaking of the entrapment cycle of the characters only comes through the existence and discovery of a tangible and visible agent of oppression that can be directly fought: the governmental cloning conspiracy and its most immediate face of antagonistic evil (played by Kiefer Sutherland.) In reality, systems of oppression are even broader, harder to identify, and much more challenging to rise up against or change.

Beyond the value of its allegorical or satirical messages, They Cloned Tyrone is a successful movie on several other levels, not least of which is simple entertainment. Even with its darker themes, the film is fun, with a frenetic energy and humor aplenty. Secondly, the performances by the cast are universally strong. The three leads shine with emotional range, each fully embodying their character. But supporting cast all give nuanced performances as well, from well-known names like Keifer Sutherland and David Alan Grier to Trayce Malachi playing Junebug or Leon Lamar playing an old drunk/prophet named Frog. Finally, the style of the film from costumes to set design works wonderfully, recalling the look of Blaxploitation while also evoking Afrofuturism.

There is a lot to unpack throughout They Cloned Tyrone, with a script filled with clever references and loads of visual details that might be easy to miss on one viewing. One of the easier to notice is the multiple references to Paul Verhoeven’s Hollow Man with Kevin Bacon and Elisabeth Shue. That 2000 movie is a version of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man novel, a title that immediately evokes Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man and its themes of being African American and invisible in society. Other references abound, and all illustrate how effectively Juel Taylor’s movie works on multiple levels and upon additional viewings. At the very least, it should not be missed.