A couple of weeks ago, I took part in a brief Twitter conversation with Teresa Frohock and Fred Kiesche that touched on the virtues of the suggested versus the explicit in the creation of terror. If memory serves (and my apologies if it does not), Robert Wise’s The Haunting (the 1963 adaptation of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House) was invoked. That film is, without a doubt, a powerful argument for the virtues of subtlety. So is the CGI-laden 1999 version, which proves just how good Wise’s approach (faithful to Jackson) was by doing the precise opposite and failing in spectacular (if entertaining) fashion. That being said, I would like to mount a bit of a defence of explicitness here. More particularly, I would like to say a few words about the value of gore.

Back around the end of the 80s, and the start of the 90s, there was a sometimes-heated debate on this subject. We had “quiet” versus “loud” horror, and this was when the term “splatterpunk” had its greatest currency. While the debates were interesting, the dichotomy was also a limiting one, as was any attempt to construct a totalizing statement concerning a field, declaring this or that approach to be inherently wrong. I find myself agreeing with the position that Stephen King outlined almost a decade before in Danse Macabre. There he distinguishes between terror (the suggested), horror (where we actually see something physically wrong) and revulsion. He writes:

“My own philosophy […] is to recognize these distinctions because they are sometimes useful, but avoid any preference for one over the other on the grounds that one effect is somehow better than another. The problem with definitions is that they have a way of turning into critical tools — and this sort of criticism, which I would call criticism-by-rote, seems to me needlessly restricting and even dangerous. I recognize terror as the finest emotion […] and so I will try to terrorize the reader. But if I find I cannot terrify him/her, I will try to horrify; and if I find I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out. I’m not proud.”

I’ve always liked this credo, but if I’m honest with myself, I’ve only really taken its lessons to heart with whatever facsimile of advancing maturity I might have. I am something of a reformed splatterpunk. In my early novel manuscripts in particular, I kept trying to top myself in terms of extremity.* I think I know better now, but that does not mean I reject the extreme out of hand. It has its place. It can be extraordinarily powerful. But its deployment must be judicious. I’ll leave it to others to decide whether or not I know what the hell I’m doing in this department, but I would like to point to some works where gore is not only used well, but where it is also crucial to their artistic and thematic achievements. My examples are films, because of the visceral impact of the visual, but I could point to print examples too. I have previously discussed the work of Lucy Taylor, for example, and it is worth remembering that even M.R. James got nasty when the spirit moved him.**

A few movies, then, that would be lessened by the removal of gore:

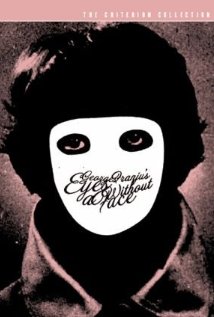

Eyes Without a Face (1960). One of the most beautiful, poetic horror films ever made, with a scene that still makes people look away, but must be confronted.

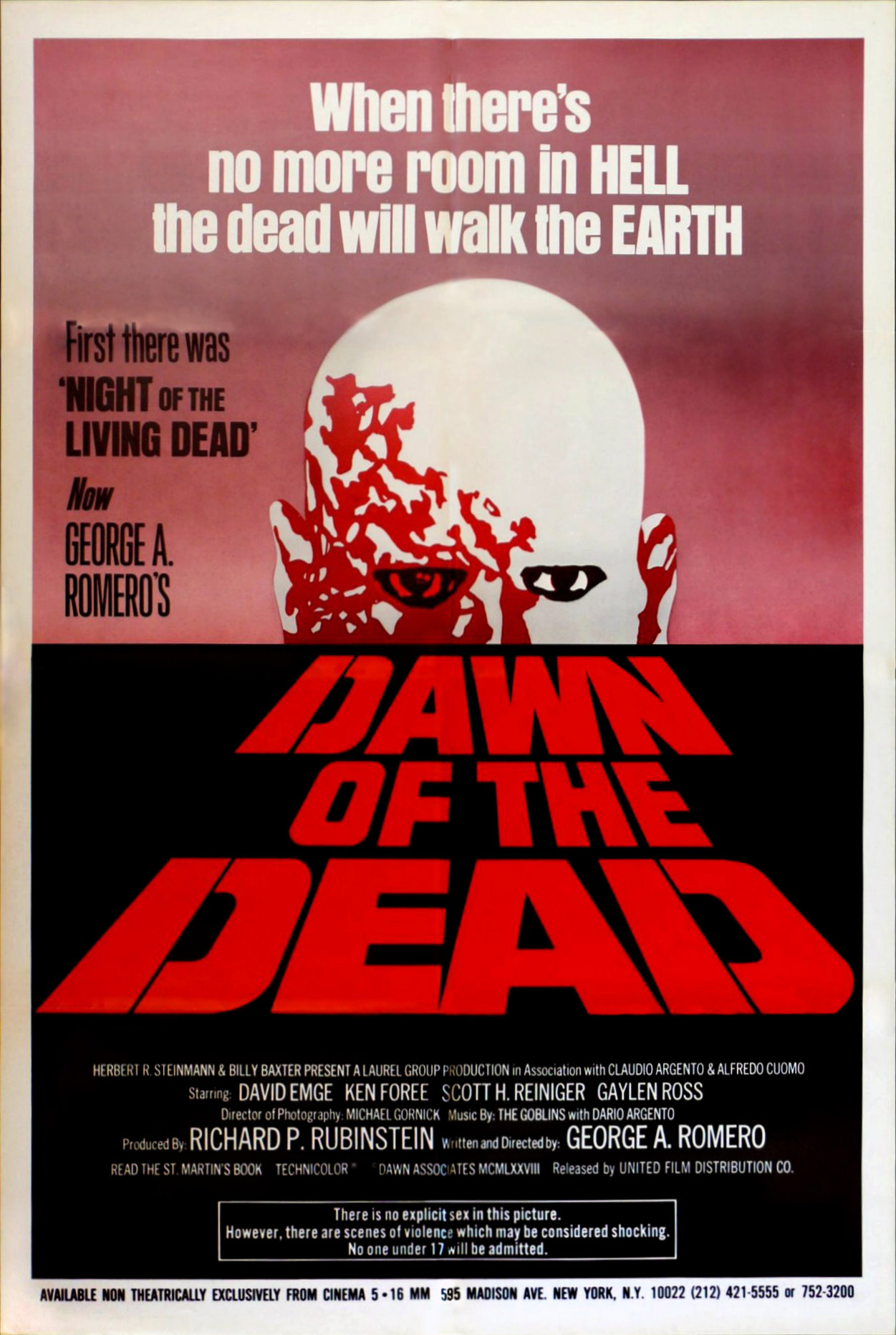

Dawn of the Dead (1978). And of course Night of the Living Dead (1968). Dawn‘s assault on the viewer’s sensibilities, however, is more concerted, and this is both the ground zero of zombie apocalypse films, and still their definitive moment. Compare the ferocious power of Romero’s film with the toothless, empty-headed World War Z. The latter film has many other problems, but its PG-13 approach to zombies is a big one.

The Brood (1979), Videodrome (1983) and The Fly (1986). I could add more of David Cronenberg’s work to the list, but these feature his most elaborate body horrors. Strip the films of these horrors, and you strip them of their heart, of their language, and of their tragedy.

Audition (1999). The first half flirts with romantic comedy. The second breaks out the razor wire and extreme acupuncture. The two halves need each other. Their synthesis is devastating.

Martyrs (2008). The film reaches an image that simultaneously references The Passion of Joan of Arc and Hellraiser. It does not do so gratuitously. It earns this moment, and its power. But the audience must earn it too, and this is an incredibly hard film to watch. As it should be.

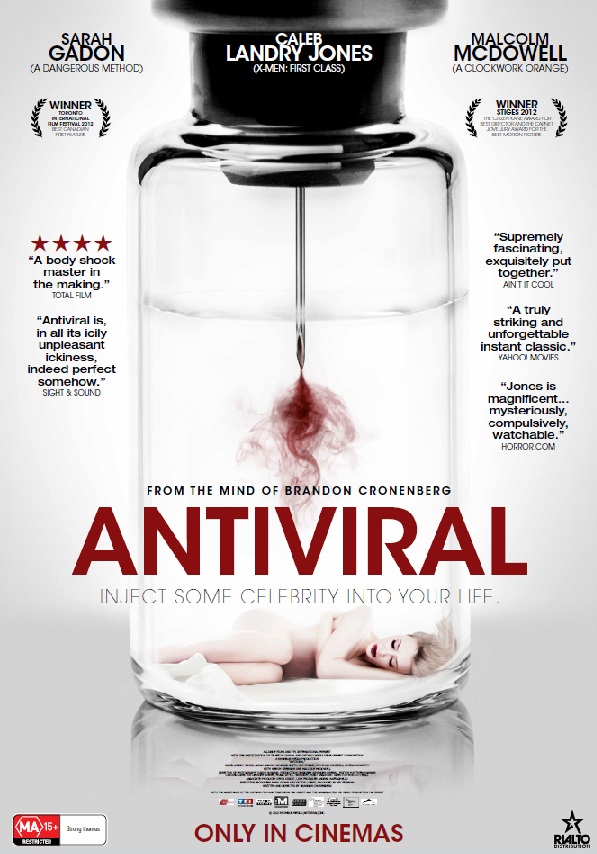

Antiviral (2012). Brandon Cronenberg’s debut is in the tradition of his father’s early work, but has its own voice. Its incisive evisceration (if I may) of celebrity culture and the brutality of patriarchal capitalism is embodied in its horrific imagery.

So there you go. Er… enjoy?

——————————————–

*I would like to take this opportunity to thank all the editors who rejected my early work. When I think about some of the content of those trunk novels, the thought of their ever seeing the light of print makes me blanch with horror.

**From “Count Magnus”: “he was once a beautiful man, but now his face was not there, because the flesh of it was sucked away off the bones.”

Audition is probably one of the most shocking uses of gore. The particular scene that you have referenced makes such an impact on the viewer almost to the point that you cannot believe what you are seeing. Brilliant post!

Pingback: Top 10 Blog Posts and Episodes for January 2014 | The Skiffy and Fanty Show