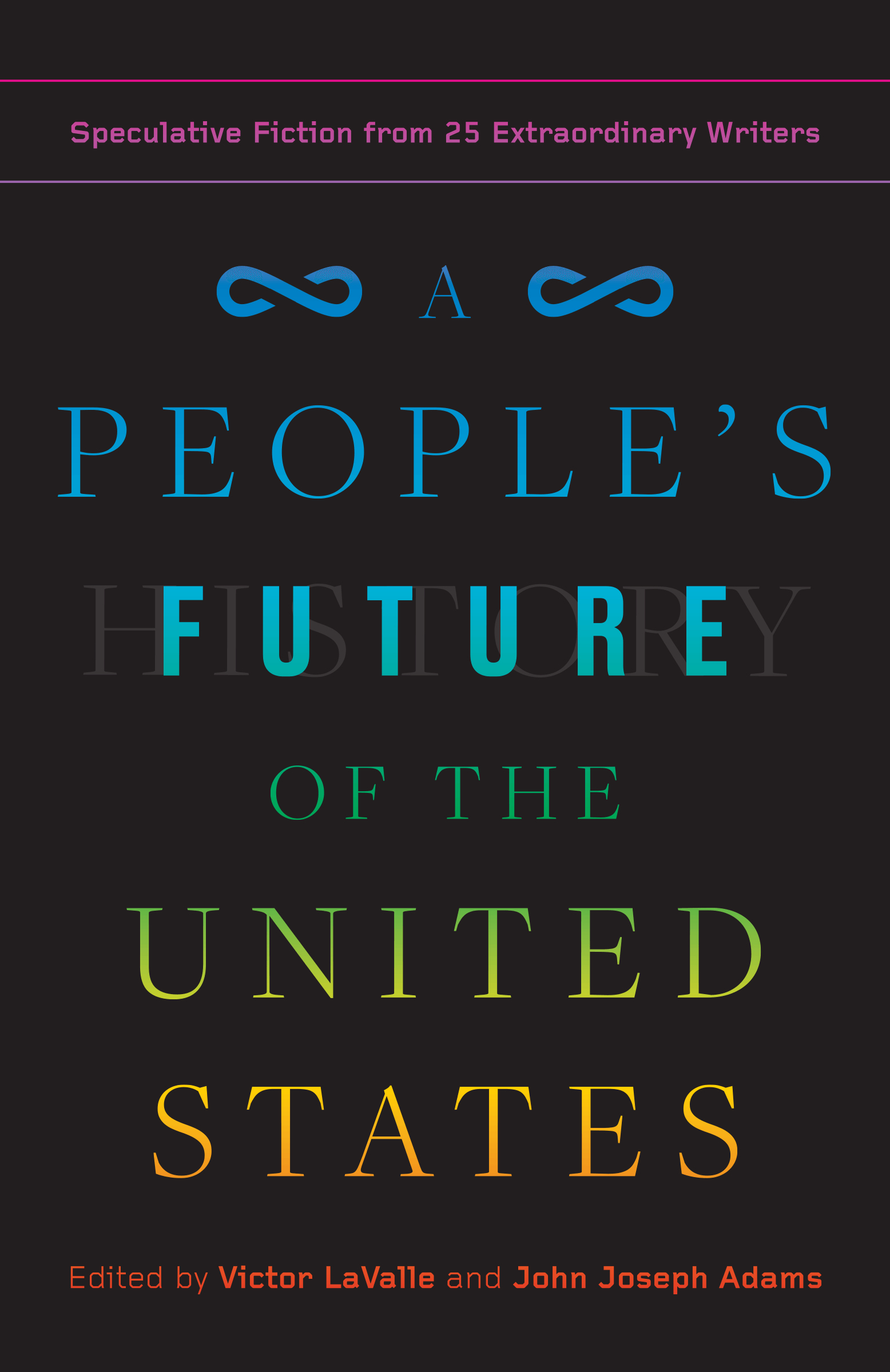

February saw the release of A People’s Future of the United States, an anthology of resistance and hope that’s edited by Victor LaValle and John Joseph Adams and features big names such as Charlie Jane Anders, Hugh Howey, N. K. Jemisin, Sam J. Miller, and Catherynne M. Valente. The anthology is filled with great work, and in particular I want to spotlight “Riverbed” by Omar El Akkad and “Harmony” by Seanan McGuire. I could easily rave about A People’s Future of the United States for the rest of this review, but I also want to spotlight some other great new stories by less well-known authors.

In February, Nightmare Magazine published “58 Rules to Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever” by Rafeeat Aliyu, a creative and disturbing take on zombies that powerfully comments on toxic social norms around marriage. This piece is dark and disturbing, so it won’t be for everyone, but if you like horror, I highly recommend it. I also enjoyed “This Wine-Dark Feeling That Isn’t The Blues” by José Pablo Iriarte, which appears in Escape Pod. It’s a short and surprising story about love, grief, and simulated realities. Lastly, I loved “Ti-Jean’s Last Adventure, as Told to Raccoon” by KT Bryski, which appears in Lightspeed Magazine. It’s a very Canadian story that’s equal parts fun folklore and serious cultural critique.

“Riverbed” by Omar El Akkad

This story has a split narrative. In the main storyline, Khadija Singh returns to Billings to visit the internment-camp-made-museum where she and her family were interned during her youth. The museum is about to formally open to the public, and the director is happy to welcome Khadija. Khadija doesn’t give a damn about the museum; she’s just there to collect her brother’s things. She insists on her status and respect, which makes her come across as rude, even though a white man acting that way wouldn’t be looked at twice. The main storyline is interrupted by flashbacks to Khadija’s youth, a time when the US government was interning Muslims and Arabs and constructing a wall along its southern border.

This story is bitter, incisive, and full of smart, sharp punches. The internment camps are hauntingly real, as is the US’s half-assed attempt to move on and learn from its mistakes. The museum feels like a gaudy, prideful thing, and Khadija’s and the museum director’s interactions highlight how deeply ingrained racism is in America. The story is somewhat hopeful, since it imagines the US recovering after a convulsion of racism, but El Akkad doesn’t let his audience off easy, as the story also critiques how thin the patina of progress truly is.

“Harmony” by Seanan McGuire

Many of the stories in A People’s Future of the United States feature a totalitarian, conservative government or a country that’s already fallen apart. That isn’t the case here. In McGuire’s story, equality is demanded by law (at least nominally) and prejudice operates more insidiously.

Miriam and Nan live in Beaverton, Oregon. On paper, it’s a charming, accepting place, but as lesbian and bisexual women, that’s not been their experience.

It was a nice place to raise a family. That was what all the advertising said. Move to Beaverton and start that happy little nuclear unit you’d been dreaming of since you broke off from the one that bore you. Find a husband, find a wife, find one of each, find someone who was neither but who nonetheless wanted to raise children by your side, file the forms and settle down, content in the knowledge that you’d be giving those little tykes exactly the kind of warm, nurturing family environment they needed to thrive.

What none of the advertisements mentioned was how difficult it was to get the licenses to start that family or how straight couples seemed to find their applications approved in half the time it took anyone else.

After Miriam and Nan’s latest application for parenthood is rejected by their homeowner’s association, they need to get away, so they go on a road-trip along the Pacific Coast Highway. On their way home, they stumble upon a curious sign: “Harmony, CA – For Sale.” They’ve found a small, isolated town for sale, which gives Miriam a wild idea: what if they bought it? What if they and some friends pooled their resources, bought the town, left Beaverton, and moved here?

This story is quieter and more peaceful than most of the others in the anthology, but in no way is it less powerful. “Harmony” playfully and intelligently interrogates the American Dream of a nice life in the suburbs and dares to imagine a more loving and just alternative. The story is a joy for how it imagines and celebrates queer family structures and kin networks, and the characters are written realistically and affectionately. In fact, I’d happily read a longer work by McGuire about Miriam, Nan, and the town of Harmony.

“58 Rules to Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever” by Rafeeat Aliyu

After Iman’s husband cheats on her, Iman decides that she’s willing to use magic to ensure her husband Kevin remains faithful and loves her—and only her—forever. The magic works, but not without side effects: Kevin develops an uncontrollable taste for human flesh, and that’s just the beginning.

This is not an easy read. Aliyu does not shy away from depicting violence, gore, and the disgusting side effects of the magic. The nauseating and disturbing elements are used to great effect though, accentuating the terrible bind Iman finds herself in. She’s torn between the shameful stigmas surrounding divorce and the toxic social pressures telling her to have a conventional, respectable marriage. As the title suggests, the story incorporates rules that good wives should follow, like excerpts from a listicle in a trashy magazine. But as Iman follows those rules—as she does everything a “good wife” should—everything goes wrong, and her life only becomes darker. Her relationship with her husband rots into something dirty and putrid, dehumanizing and terrifying.

In some ways this story pairs well with “Harmony” by Seanan McGuire. (This story being much darker.) Both stories examine marriages, social norms, and what it takes to be happy. In “Harmony,” Miriam and Nan are able to find some happiness by eschewing the normative, supposed-desireable life in the suburbs, whereas in this story, Iman basically brings about her downfall by doing everything she’s “supposed to.”

“This Wine-Dark Feeling That Isn’t The Blues” by José Pablo Iriarte

At 1,600 words, this story is only slightly longer than a piece of flash fiction. It’s a heavy story about love and grief featuring two girls who meet in a recovery center and who each struggle with their own mental/emotional health. It’s also a creative and surprising take on the question: are we living in a simulation? If either of those aspects pique your interest, I highly recommend you check this one out.

Side-note: José Pablo Iriarte’s story “The Substance of My Lives, the Accidents of Our Births,” which appeared in Lightspeed Magazine in January 2018, was recently announced as a finalist for the Nebula Awards. I reviewed that story back in my first short fiction review for Skiffy and Fanty, and I highly recommend you check it out!

“Ti-Jean’s Last Adventure, as Told to Raccoon” by KT Bryski

Wow. I really love this story. It does a couple things that I really like, and it does those really well.

First, it’s a folktale/fable that comments powerfully on real world politics. As Bryski mentions in the accompanying author interview, she wrote this story for Canada’s sesquicentennial (150th anniversary), and the story wrestles with Canada’s history of settler colonialism and racism in ways that are simultaneously sophisticated and fun.

Second, it’s a framed story in which the narrator tells Raccoon the story of Ti-Jean’s Last Adventure, and Raccoon frequently interrupts the story with interjections that are equally humorous and profound. I love stories that get a little bit meta, that are willing to interrupt themselves. This story does that to tremendous effect.

“Hold on,” Raccoon says, digging into the takeout boxes. “Snack break.”

“What are you eating?” I ask.

“Pork bun. Goat roti. Falafel.”

“Nothing Canadian?”

Tahini coats his whiskers. “Tastes Canadian to me.”

As soon as I finished this story, I immediately reread it. On the first read, I was mostly invested in Ti-Jean’s story, although I enjoyed Raccoon’s interjections as well. On the second read, I paid more attention to the interactions between the narrator and the Raccoon, and it gave the story so much more depth and meaning. There’s a fun story on the surface here, and there’s a serious, challenging story one layer beneath. Go read them both.