Brutality. With only a bare-bones plot and scant references to contextualize the national conflict that gives the film its name, Alex Garland’s Civil War is a showcase of human brutality wrought equally by character action and inaction.

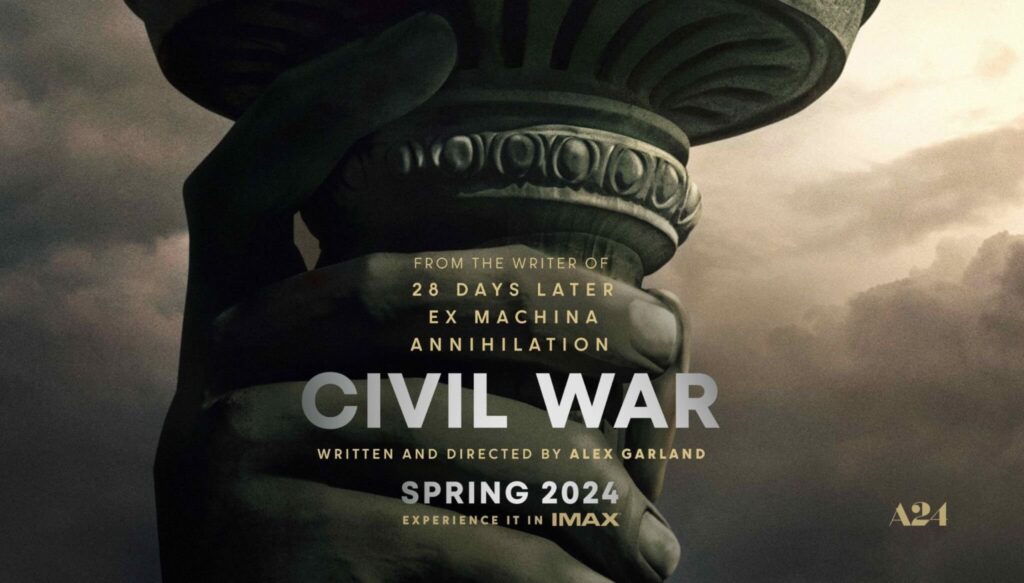

For anyone who has seen one of Garland’s films before, they should know that initial expectations or marketing might not reflect what the film actually is, or what themes it’s really digging into. Prior to viewing this new film, I’ve only seen Ex Machina and Annihilation, both of which I adore, and have used in one of my Honors courses. They are both movies that invite a spectrum of interpretation. When I’ve read the reactions of others to those films, I’ve usually concluded that either those viewers missed out on important facets of Garland’s work, or I’m giving Garland far more credit of depth and brilliance than deserved. That trend continues with Civil War.

On its surface, Civil War is an action war movie, set in a near-future fractured former United States of America that closely resembles something either side of the current political dichotomy might see in their crystal ball. The President, played by Nick Offerman, is portrayed as both an executive trying to hold the Union together against unlawful secessionists, and as an authoritarian who has oppressed the nation, stifled dissent, and seized a third term of office.

Within this national backdrop, a small group of photojournalists embark on a dangerous journey from New York to Washington, D.C., with the goal of reaching the reclusive President for a final interview before the fall. The respected, veteran war photographer Lee Smith (Kirsten Dunst) leads this group with her colleague/partner Joel (Wagner Moura). Joining them is Lee’s elderly mentor Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson) and Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), a brash, young, aspiring photojournalist who Lee saves while documenting a protest/suicide bombing in Brooklyn.

Nothing about that summary, or the construction of the film’s trailer around it, made me consider this a movie to see. Quite the reverse. However, I saw Garland’s name and realized: oh, this can’t be what this movie is really about. Thankfully, this is so. The plot of Civil War actually doesn’t matter at all. It’s just a backdrop of events to explore the worst of human selfishness. In that regard, bringing up plot holes or asking whether elements of the story here are ‘believable’ or not are really beside the artistic point. Such critiques could and do exist, but if they are what are making or breaking Civil War for you, this (and Garland’s works in general) probably just isn’t (aren’t) for you.

The details of the sociopolitical conflict that underlie Civil War do not matter here, nor do the identities or moral imperatives of any of the sides. This is not a modern repeat of the late 19th century U.S. Civil War, this is chaos. Garland has no interest in the politics, or on figuring out who the good, the bad, or neutral are. The interest here instead is on the simple outcome of this chaotic conflict for the characters and how they meet it and are changed by it.

That simple outcome is the brutality and the ways in which it creates monsters out of all in order to survive. Civil War depicts a situation where American society is brought to a primitive and selfish level of kill or be killed. Garland hammers that message again and again through the film, like the repetitive poundings of bullets and artillery. Toward the middle of the movie it’s given most literal representation and explanation in the dialogue when the team of traveling journalists are pinned down on the side of the road along with some soldiers, taking fire from an unknown sniper in a distant building. Joel keeps asking the soldiers for context of what is going on, and why. The soldiers look at him incredulous. There is no rationale here. It doesn’t matter who is doing the shooting, or what they stand for. You’re being shot at. Shoot them first so you don’t end up dead.

There’s the brutal truth and that’s what Garland is focusing on here. Trying to subscribe rhyme or reason to madness and chaos of war like this is foolish, even more irrational than the reality confronting us. The conflict of Civil War and the brutality it generates create obvious monsters to double down on the brutality in a positive feedback loop. Racists who use the chaos as an opportunity to kill with righteous impunity. Soldiers on each side killing for patriotism or to defend against despotism.

But Garland also shows the brutality and monsters that arise from inaction. There’s a town that buries its head in the sand from the surrounding conflict, going on with lives as if nothing is going on outside the town borders. Though they stay out of the conflict, snipers from the rooftops are needed to maintain that normalcy facade. Ignoring the large conflicts keeps them safe and happy, but only by selfishly ignoring and shutting off the human turmoil beyond.

The most intense brutality from inaction depicted in Civil War, however, is from the arcs of its main characters, the photojournalists. Staying out the conflict as non-combatants, they ride in a vehicle marked press, and bear the same markings on their helmets and Kevlar armor. Their job is to stay outside the conflict, yet they are embedded directly in it, getting in the way even. Lee explains to Jessie that the war photographer’s role is to simply observe and report for others to make judgements. They must maintain an emotional and political distance from what they document, even if their lives may be under threat.

However, the conflict makes these photojournalists into a fiercely competitive group out to get the reportage and the perfect shot at any cost, even one another. Again and again Garland shows the selfish brutality of his characters that comes from the emotional walls they put up to pursue their jobs and the photographs. And he shows that whenever those walls ever begin to break down to allow in the faintest trace of human compassion in place of pure selfishness, well, that’s when you die.

For all the moments of brutal physical violence of warfare, the character of Jessie may be the most monstrous and destructive. She presents as young and naive, yet uses that to exploit and get ahead. She’s not actually that naive, she’s just inexperienced, very fearless, and very selfish. Based on other reviews I’ve seen, she’s even managed to fool a lot of viewers. Several negative reviews of the movie expressed anger that Lee and Joel put a young girl at such risk by taking her along to D.C. Yet, the movie even makes that point that though she looks very young, Jessie is actually 28 years old. Similarly, the actress Cailee Spaeny is in her mid to late twenties, but could pass for far younger. Jessie uses this to get what she needs from her mentor and idol, Lee.

It’s easy for viewers of Civil War to get caught up and empathize with the main characters. We see how the brutality of the conflict affects them, and how it truly breaks them up when they lose beloved friends or puts them at death’s door. But then all that hits the viewer even harder when we see those same characters stand aside and abandon one another for their own selfish goals. It just adds to the brutality.

In Annihilation I saw a lot of influence from Andrei Tarkovsky in Garland’s film. With Civil War, the inspiration and comparison leans more towards Kubrick. A friend of mine who watched the movie with me pointed out how much the direction of the action sequences and use of sound in the movie reminded him of the second half of Full Metal Jacket. It’s an accurate observation, from the long, meticulously crafted shots and staging, to the juxtaposition of silence, blasts of warfare, and soundtrack sampling. I can see how the darkness of its theme, and its minimalistic plot, might draw viewers away from Civil War. But that doesn’t negate just how well made the film is, nor how well acted it is. The powerful nuanced performances by Dunst and Spaeny should get particular attention.

This is Skiffy and Fanty, so one might wonder after all of this how Civil War really qualifies in the broad genre or in what way it might be an interesting addition to the genre. It technically qualifies merely by taking place in the future – even if near – and as being an alternate history of the United States in that there are no references to actual politicians or parties. But what attracts me to it as speculation would be that similarity to Full Metal Jacket, a film that works only in reference – and almost parody – of a Vietnam War that occurred decades prior. Civil War is the same, but referencing a war that hasn’t occurred yet, as if Garland had made this in some alternate future.

And even though the plot and politics of Civil War aren’t at the heart of what it’s actually about, Garland still does seem to be asking both sides of today’s political schism in the United States to consider what could come from such a continued path toward chaos and irrationality. Irregardless of right or wrong, let’s not take this to the level of kill or be killed and the brutality that makes for all.