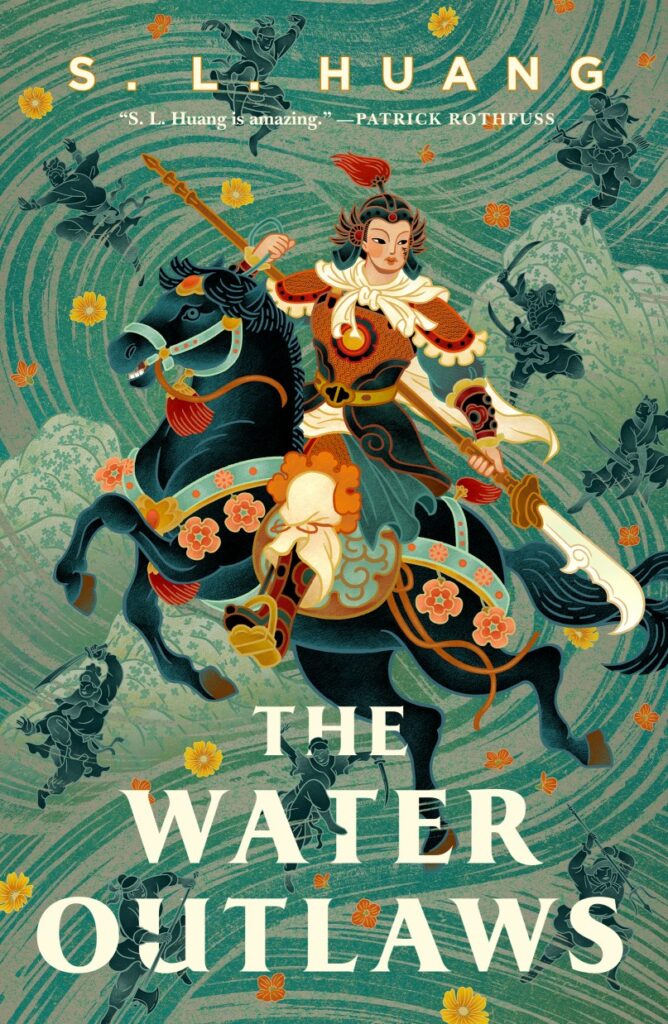

We are pleased to have this interview on the Skiffy & Fanty blog with S.L. Huang about their newly released novel The Water Outlaws, out now from TorDotCom in the US and Solaris in the UK.

“Inspired by a classic of martial arts literature… the Water Outlaws are bandits of devastating ruthlessness, unseemly femininity, dangerous philosophies, and ungovernable gender who are ready to make history—or tear it apart.”

In addition to this interview, you can read the first two chapters of the novel online at Tor.com, and can also check out Paul’s review at Nerds of a Feather or Daniel’s review at Reading 1000 Lives.

For more details on the novel and its author, please read the official book blurb and author information that follow the interview or check out the links provided by SL. Thank you again to SL Huang for doing this interview with us and giving us a great read!

Q1. Based on Daniel’s understanding, the original story depicts women poorly in all regards, from physical appearance to behavior. Did that influence how you approached depicting the male characters in The Water Outlaws?

Interesting question!

Yes, women are depicted poorly in the original…but with caveats. Though 105 of the 108 bandits are men, the novel does have three EXCELLENT female characters, one of whom is clearly shown outfighting most of her martial brothers. But then after that, yes, they do treat her poorly too, marrying her off to the one bandit who is basically portrayed as a sexual predator—which behavior, frustratingly, is equated with him wanting a wife (the rest are largely uninterested in sex, and there’s as much to unpack there as it sounds).

Credit: Chris Massa Photography

That character’s portrayal in Water Margin definitely influenced how I wrote her—I kept her a woman, and her reason for joining the bandits is running from an unsuitable marriage…ha.

And yes, those three female bandits aside, the misogyny in the original is extremely not great. Women are either absent, adulterers, or victims, aside from the odd pure and noble honor suicide.

But it didn’t really influence how I depicted the men, I don’t think? I wasn’t interested in doing this as a revenge tale where I turn the men into caricatures, or in making them only absent, adulterers, victims, or noble suicides. I’m just not interested in any sort of gender essentialism, even when I’m highlighting gender diversity, women, and queerness among my leads!

Thus, there [are] many men shown throughout society in the book—some of whom are main characters, and some of whom are not—and I strove to do the same thing I tried to do with the bandits: show many truthful-feeling strands of reality. Some are sexist, some are not; some respect the non-male characters, some do not; some strive to be good people but simply don’t think about the values their default society is upholding…

Q2. Aside from the characters and plot, were there aspects of Water Margin that you wanted to keep/adapt for The Water Outlaws, such as its style and themes?

Here are some things I definitely wanted to keep:

1) That it’s FUN.

2) That it’s full of action and adventure—it’s often considered the first wuxia novel.

3) That it didn’t whitewash the brutality of some of the bandits, maintaining their moral grayness (though I perhaps dig into that and question it a little more than the original!).

4) That some of the key sequences (the inciting action against Lin Chong, or the birthday present heist) would feel resonant with the original depictions, even if they had some small alterations (for example, I changed slightly which characters go on the heist).

5) That I retained a lot of “feel” of cultural values that lean toward Chinese defaults in the way the characters see the world, and that it didn’t feel like I was imposing Western ones (for example, I did a lot of research on how Chinese societies have historically treated queerness and gender).

6) That the characters could feel resonant with their originals as well. For example:

- I moved Lu Junyi’s storyline significantly but kept the character a wealthy and privileged martial artist (with marital problems…).

- I kept Lu Da jovial, unprivileged, a failed monk, and abusive to trees.

- Song Jiang is a charismatic and philanthropic poet rather than a charismatic and philanthropic clerk, but made that change as a reference to poetry-writing being what got Water Margin‘s Song Jiang in such very deep trouble…

- And I kept Li Kui very nicely vulgar and violent!

With some of the more minor characters the resonance is lighter—for example, Ling Zhen is indeed the gunpowder expert and Fan Rui has supernatural powers in the original, but other than that I pretty much recharacterized them thoroughly—but for most of the leads I really wanted them to “feel” like a refracted version of these characters I loved. I would say pretty much all of the main bandits as well as the two main villains I was gleefully running down a rabbit hole with at least a kernel of their O.G. characterizations!

Q3. One of the dominant themes in the novel appears to be the journeys of self-discovery by the characters: that they can be more, greater than they were in the past—or than how they currently view themselves—particularly when coming together in sisterhood. How did you arrive at this focus?

This is one of those questions where I feel like you interviewers are so much smarter about my book than I am! Although certainly I wanted to show things like character growth and the bonding of those relationships, I don’t know that I was consciously planning anything as impressive as you’re describing…though I love that you see it as one of the main themes!

Honestly, I was just trying to write characters who feel “real”—especially in the context of oppression and lack of choice, where people’s decisions can be all over the map, but are still decisions we can understand. That’s something that truly fascinates me, and that I feel gets one-dimensionalized out of our modern discourse a lot…that the way decent people react against tyranny can have all these different forms, some that are so extremely opposed to each other that even people in the same community with the same interests might have vehemently different stances.

Some of those choices we might agree with and some not, and of course I have my own opinions, but what I wanted to dig into was the understanding. To see all these different ways of viewing the world—and evolutions of viewing the world, and difficult ways of engaging with an oppressive society—as sympathetic. Even, maybe especially, if you think the character’s making exactly the wrong call.

If that ended up giving me the character growth you describe, I’m very pleased!

Q4. Was there any character you felt closest to or most eager to write about?

To be honest, I enjoyed them all, but if I had to pick a favorite it’s probably Wu Yong. I think my Wu Yong is delightfully manipulative and sociopathic, in a way I think is tremendously fun to write. (But always all for the good of the people, of course.)

Wu Yong’s POV chapters were an additional craft challenge because I wrote them all without ever giving a third person pronoun anywhere. No gender is ever stated, and the other characters use the title “Professor” instead of “Sister”/”Brother” (which is completely in keeping with Water Margin‘s characterization). In my mind—and as is alluded to in another part of the book for eagle-eyed readers—the characters are all speaking a version of fantasy Chinese, which doesn’t gender its third person pronouns (and didn’t gender them even in writing till the 20th century). That puts this book under “translation convention”, but it makes the “translation” of personal pronouns for nonbinary people challenging. Nobody’s ever misgendering anyone via pronoun, but neither does anybody ever need to ask about pronouns—pronouns are simply not a thing that relate to gender.

Some of the other trans or nonbinary bandits do have translated pronouns that work in English—Chao Gai, for example, is what we might call bigender, and we mainly see her among the bandits, where she lives as a woman. The bandits who are binary trans or GNC are of course “translated” with their correct binary pronouns in place, and I do use they/them for a tertiary character as well, but what felt truest to Wu Yong was that no translated pronoun felt quite right, especially given the entire lack of thought the characters would be giving to pronoun-ing in an otherwise sexist society.

And thus, I decided that the best “translation” for Wu Yong’s pronouns was none at all.

To be clear, I’m not attempting here to leave ambiguous that Wu Yong might be male or female. The book isn’t trying to create mystery or bait people into figuring out that Wu Yong is “really” one of the two binary genders; instead I’m trying to portray a nonbinary character as I think is correct for that characterization. Wu Yong doesn’t even go by a gendered kindred term as some of the other trans and nonbinary bandits do (incidentally, in real life, kindred terms are something the Asian nonbinary people I spoke to felt quite non-monolithic about—which I’ve attempted to port into the book by subtly writing many of my trans, nonbinary, and GNC bandits as having made different choices about it).

I know de-pronouning has been done in first and second person before—heck, I’ve done it in first/second person before!—but I’m very curious if anyone else has ever done it in third person with one of the POV characters of a novel.

I’m also fascinated to hear if people notice, if it’s not something they knew beforehand. To my knowledge none of the early reviews have mentioned it as either well done or not, which I assume means that either people think the rendering is perfectly decent but unworthy of particular note…or it’s smooth enough that readers simply aren’t noticing. I admit, that would tickle me greatly.

Q5. Paul has been following your work since Zero Sum Game. How does your writing of action scenes first seen in the Cas novels help prepare you for writing the cinematic Wuxia-styled sequences in The Water Outlaws?

I don’t think of it as one having prepared me for the other, really—it’s pretty much felt like the same process! Although of course I’m a more experienced writer now.

The greater preparation I did for this was to pretty much immerse myself in wuxia media for approximately a year, both before and during the drafting. Which, of course, was extremely fun, (twist my arm why don’t you!). Obviously it was part of my media consumption already, but I really wanted to feel like I was getting that “vibe” right, so I wanted to surround myself with all different examples of it as much as possible while writing.

Q6. The major “fantasy” element to The Water Outlaws involves God’s Teeth, ancient, stone-like relics that form a connection with users to impart supernatural powers. These objects, and the sub-plot around their creation is a great strength of the story that doesn’t (to our knowledge) come from the traditional tale. How did you come to conceive of them for this narrative, and do they have any relation to scholar’s rock (gongshi)?

Yes! The inspiration for the scholar’s stone in the book is exactly 供石. Nice catch!

There’s some of my own indulgence here, really, because I was the type of fanciful child who would climb trees and make up fairy stories about the secrets in nature (as many of us SFF folk did, I’m sure). I think 供石 is fascinating and gorgeous and I’ve gone to parks where there are huge ones and I would curl up as small as possible in a little nook of it. There are quite a few things in nature that have always felt magical to me, and I always love writing them into stories.

I’m not the only one to feel its enchantment, either: from what I understand it does have significance in Daoism and other aspects of Chinese culture, religion, scholarship, or mythology.

But! It’s not quite true that 供石 isn’t in the original—in Water Margin, it is almost certainly the cargo Yang Zhi is supposed to have lost on the river, resulting in demotion and mistreatment by Gao Qiu (and then, eventually, becoming custodian to the birthday presents that the bandits aim to steal). Water Margin gives the stone no described magical properties; it’s presumably desirable as an ornamental stone, as it is in real life. I had such an enchantment with it already myself though that once I figured out what Yang Zhi’s cargo was supposed to be, I enthusiastically took that and ran with it! The god’s teeth that come from it are indeed my own invention, however.

The rest of that plotline is my love letter to Song Dynasty history, and the scholar’s stone provided this lovely connection to both Water Margin and my own emotional delight with 供石.

Q7. Like its basis, The Water Outlaws is set during the Song Dynasty of Chinese political history. The novel does a good job in grounding a Western reader who may be unfamiliar with this history, and it shows its appreciation for aspects of that era. What other reading or knowledge of the period did you draw upon to create the world of the novel?

Hahaha I did so much research I felt like I could have written a master’s thesis on the Song Dynasty by the end.

That said, it’s not quite the Song Dynasty—by making it technically a secondary world I gave myself an “out” to break some of the historical truths if I needed or wanted to (switching around the timelines of various inventions, etc). I very much tried to do that consciously, though. Which led me to spending hours and hours researching the history of hinges or whether they had oil lamps or making sure I didn’t mention glass anywhere…I also ended up with a hundred-page wiki on my world by the time I was done.

Q8. Did any anime, movies or other media inspire your characters and your take on the events of the book?

Nope, not really! I’ve consumed a lot of Chinese media (including a number of Water Margin adaptations), but as far as I can say, the direction I took the characters was my own. I’m sure there are plenty of minor influences knocking around in there, but nothing conscious enough for me to name.

Q9. Is it correct that the characters and events of The Water Outlaws could continue with sequels, drawing further on the plot of the Water Margins inspiration text?

Yep! I actually have rough outlines for books 2 and 3 and they were part of my proposal to Tor. I’m only contracted for one, though, so if you want sequels, tell all your friends to buy The Water Outlaws!

It was important to me to write this one in a way that stood alone but also left the door open. Funnily enough, it also fits a bit with Water Margin history, as there are 70-chapter, 100-chapter, and 120-chapter versions of the original, and this one ends roughly where the 70-chapter version ends.

If it does well enough for Tor to ask me for sequels, I’m willing to write them!

Q10. Is there anything else you’d like to tell Skiffy & Fanty followers about The Water Outlaws or other works of yours?

The Water Outlaws is definitely the number one thing eating my life right now, but lately I’ve also been doing a lot of game writing—for something completely different that has no violence at all, I have a contemporary cozy baking show game up on Storyloom. It’s interactive fiction where you’re a geeky engineer who enters a baking competition!

Tina Connolly and I are also almost done serializing a shared-world comedic fantasy game that’s an absurdist fairy tale remix, in which Red Riding Hood is best friends with the Wolf, Rapunzel turned her hair into snakes (she was sick of people TOUCHING IT), and Jack is a con artist and thief with socialist leanings and a hobby in magic bean hydroponics. It’s fun and funny and queer and full of feels (and Tina is HILARIOUS and amazing!). Tina’s half is here, with the wonderfully dysfunctional and somewhat violent royal princesses. And I’ve got the scrappy woodlanders! (Likewise dysfunctional and somewhat violent. But good hearts.) We designed them so that they can be read separately but they’re definitely better together; I recommend starting with Tina’s and then switching back and forth every quest.

The Storyloom site/app are still in beta, which means everything’s still free at the moment, if you want to check out some of my interactive fiction!

But The Water Outlaws is the behemoth of my year, and you can order it in the US from TorDotCom or in the UK from Solaris. There’s also an audiobook read by the fantastic Emily Woo Zeller! If you’d like to be updated on more book news whenever I can announce it, my website is at slhuang.com and you can join my mailing list at https://www.slhuang.com/mailing-list/.

Official Book Blurb:

In the jianghu, you break the law to make it your own.

Lin Chong is an expert arms instructor, training the Emperor’s soldiers in sword and truncheon, battle axe and spear, lance and crossbow. Unlike bolder friends who flirt with challenging the unequal hierarchies and values of Imperial society, she believes in keeping her head down and doing her job.

Until a powerful man with a vendetta rips that carefully-built life away.

Disgraced, tattooed as a criminal, and on the run from an Imperial Marshall who will stop at nothing to see her dead, Lin Chong is recruited by the Bandits of Liangshan. Mountain outlaws on the margins of society, the Liangshan Bandits proclaim a belief in justice—for women, for the downtrodden, for progressive thinkers a corrupt Empire would imprison or destroy. They’re also murderers, thieves, smugglers, and cutthroats.

Apart, they love like demons and fight like tigers. Together, they could bring down an empire.

Official Author Information:

S.L. Huang is a Hollywood stunt performer, firearms expert, Nebula Award finalist, and Hugo Award winner with a math degree from MIT and credits in productions like “Battlestar Galactica” and “Top Shot.” The author of the fantasy novella Burning Roses as well as the Cas Russell novels including Zero Sum Game, Null Set, and Critical Point, Huang’s short fiction has also appeared in Analog, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Strange Horizons, Nature, Tor.com, and more, including numerous best-of anthologies.