“There are no correct alternate histories, there are only plausible alternate histories.” – Will Shetterly

Will Shetterly’s statement above hinges on the word plausible. Shetterly’s statement is facile, but it hinges on the unspoken assumption that everyone can agree on what a ‘plausible’ alternate history is and is not. For example, to a first approximation and for a lot of casual readers, George Washington taking the monarchial crown that was offered to him might seem like a rich and interesting alternate history. King George of America! Those more versed in the biography of Washington, however, would reject such an alternate history as being flatly impossible, given his attitudes and basic nature. The reverse is true for small, seemingly innocuous changes that casual readers might consider not large enough of a hook to change the world, but experts in the subfield might consider crucial to the flow of history.

Three novels I’ve recently read have gotten me to thinking about alternate histories, but instead of the word plausible, I’d like to focus on a somewhat different formulation: ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ alternate history. Neither of these are a value judgement on the type of alternate history, but rather describe the world of the novel’s historical relationship to our own. And, of course, it’s a spectrum of description. Novels can be more hard or more soft than others.

In a hard alternate history, epitomized by the work of authors such as Harry Turtledove, the differences from our world, where, when and why are worked out with a strict adherence to historical events in our world and in the new world. The story or novel may or may not spell out the change explicitly, but it’s always there at least implicitly for the reader to tease out, sometimes as a game or challenge for the reader: can you figure out when and where history changed from our own? The joy and value of reading the hardest of AH comes from looking at how the author has worked out the divergent world in a rigorous manner.

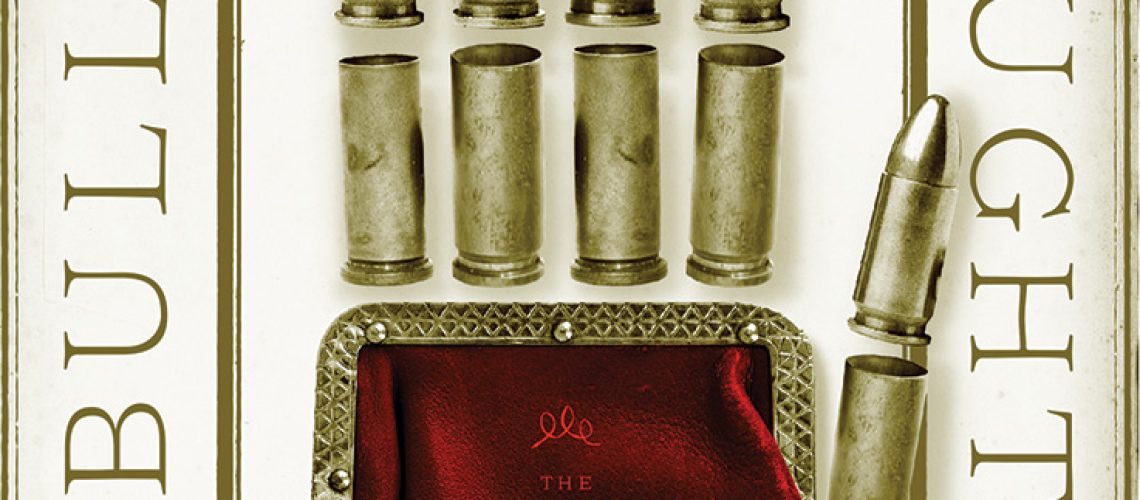

The Bullet Catcher’s Daughter, by Rod Duncan, fits firmly in the higher hard portion of the alternate history spectrum. There is a definite, definitive point of divergence between our world and the split-England of the novel. Not being as familiar with British history as I’d like, the exact point of divergence was somewhat nebulous for me, although a glossary at the end set me to rights in revealing just where England broke into two very different nations.

The Bullet Catcher’s Daughter is the story of Elizabeth Barnabas. Having fled her home (and nation) years ago onto a houseboat whose rent she is always on the edge of not being able to pay, she works as a private investigator under the alias of her imaginary brother. An offer of employment materializes for a case that would give Elizabeth the money she needs not only to pay off the boat and escape her precarious circumstances. The characterization is excellent, and we slowly tease out Elizabeth’s history as the novel progresses, which is one of the real joys of the novel. The other joy of the novel, however, is how meticulously Duncan has worked out the reason and the consequences of England’s crazy-quilt split into two countries. Both descendant nations are distinctly different, and their nature and subsequent evolution rational and logical. Watching the worldbuilding of both nations unfold is wonderful process of immersion.

By contrast, The Time Roads by Beth Bernobich is a quartet of novellas set in an alternate world where Eireann (Ireland) is a major world power at the end of the 19th and into the early 20th century. The four novellas follow the ascension of a Queen, the trials and tribulations of her trusted advisor, and a brilliant mathematician and the struggles of all to maintain themselves and, further, Eireann’s place in the world. This struggle within and without reaches a crescendo as the potential of travel through time threatens to undo or unravel the work of generations. Each with a different tone and focus, the novellas are windows into what turns out to be a seminal time for Eireann and the two major protagonists in the bargain. The character development and choices Aine, Síomón and Aidrean each agonize over makes for a rich meal of an overarching story. The author handles it expertly and well.

The alternate historical aspects of the novel are there, but not strictly explicated in meticulous detail. By the time I read all four novellas, I had a vague sense of how Eireann came to be the dominant power in the region (and beyond). I think, if I squint, I can see the point of divergence in a side comment in one line of one of the stories. But the point of divergence is not the point of the book at all. The Time Roads, playing to the strength of the author’s writing, is far more interested in the handful of characters and the consequences and challenges of exploring time travel than in the timeline’s original foundation.

Soft alternate history, then, is alternate history that is not interested in defining a specific point of divergence at all. There is no one point or event, implied or otherwise, that the reader can identity as the place where this world’s history diverged from our own. There seems to be one, but it’s not pointed out or alluded to in the narrative, and in general, it is not what the author is interested in at all. Further, soft alternate histories may eschew a divergence point altogether, instead portraying an alternate world that has no definitive branch point from ours.

The soft alternate historical world that the author portrays in this latest category is similar, but distinctly different to our own, but there is no traceable path on how that world diverged from our own, or why a world with different ground rules to ours has had a history very similar to our own for much or all of time. These novels often like to use characters from our own world, in the new and different alternate worlds that the author has created. Part of the joy of reading these novels is to see familiar historical characters cast in new and interesting situations.

The Shadow Master by Craig Cormick falls into this soft portion of alternate history. The Shadow Master takes place in the unnamed ‘Walled City’, which may be Florence in an alternate Renaissance Italy, given the presence of the Medici family in the narrative. This world, with a scientific system of magic being rediscovered from a fall from the heights of the ancients, is a metaphor for the rediscovery of the knowledge and heritage of the ancient world in our own history. The novel pits the Medici family, a powerful banking family in our own history, against the more imaginary Lorraine family, for control of a city which to all appearances is the last bastion of civilization in a wasteland of plague. Leonardo da Vinci works for the Medicis as their scientific (sorcerous) advisor, and the Lorraines employ Galileo Galilei in a similar role.

Part of the fun of the novel, besides the wordplay, is seeing the differing strands of the scientific magic each of the two advisers, and thus the families, employ in a struggle against each other. All of this is a frame, really, for a love story out of Romeo and Juliet, and a more mysterious struggle, still. The novel embraces its soft alternate historical nature and lets the ‘rule of cool’ outweigh any strict concerns about the plausibility of the world’s history. The novel is simply interested in cool scientific magical creations, the aforementioned love story, wordplay, and the idea of having a pressure cooker of a city on the edge.

Will Shetterly said there are no correct alternate histories. I would say that there is no correct form for an alternate history. Be it playing with a historical change and its consequences or using an alternate history to speak to our own world and history by means of clever allusion and parallel rather than historical branch point, alternate histories ultimately depend on the strength of the author’s writing to evoke the characters and their world. It is that which an alternate history can and should be judged on.

4 Responses

That’s an interesting way of differentiating different alternate histories without being judgemental about it, and an approach I really like. I think your reference to the ‘rule of cool’ really helps pin down the distinction for me. Soft alternate history is about what feels awesome and exciting, it’s more emotionally derived for the writer and the reader’s response to changes is more about the ‘wow!’ factor. Hard alternate history is about the intellectual endeavour of working out in detail what would happen. That can definitely be emotionally satisfying, but it doesn’t cut so directly to a gut reaction. It’s getting to the reader through their head, rather than reaching straight for the heart.