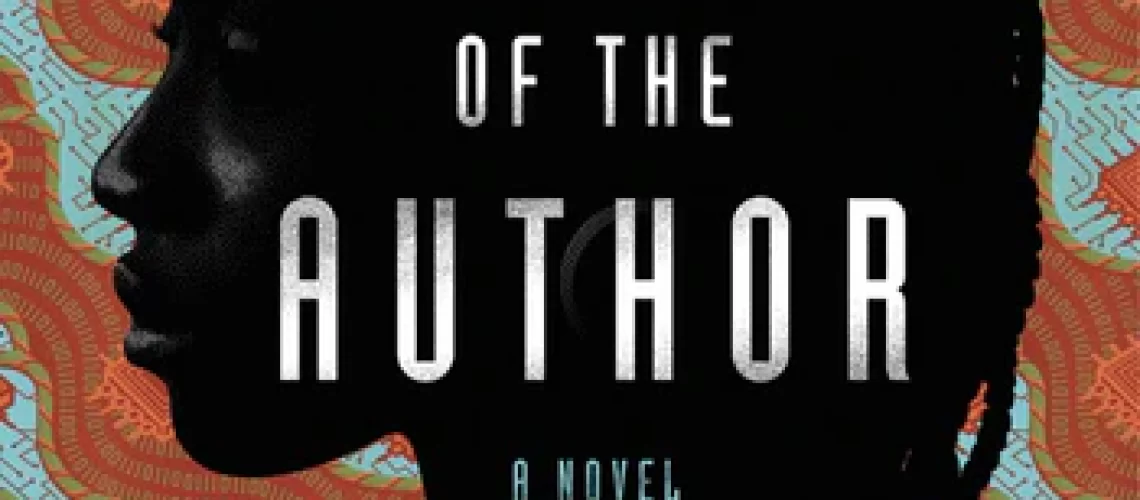

Nnedi Okorafor’s new book, Death of the Author: A Novel (out Jan. 14), is a great book that deserves all the attention it can garner. I love the vivid characters in it, the way they face their challenges, the fiercely exuberant explorations of personhood and choice and negotiating relationships, and the sheer joy of life apparent in how Okorafor plays with ideas.

Per the publisher, HarperCollins, “In this exhilarating tale … a disabled Nigerian American woman pens a wildly successful Sci-Fi novel, but as her fame rises, she loses control of the narrative—a surprisingly cutting, yet heartfelt drama about art and love, identity and connection, and, ultimately, what makes us human.”

I usually feel that naming a book [Title]: A Novel is a bit pretentious, but in this case the “A Novel” appendage is helpful, distinguishing Okorafor’s work from the 1967 Roland Barthes essay, “The Death of the Author.” Traditional literary theory often looks to authors’ biographies and culture (and stated intentions, if any) for clues to interpreting their work; in contrast, the “death of the author” theory can be summarized as saying that no text can have an ultimately correct interpretation, but rather they are all recast anew by each new reader’s reaction to them. The initial relationship with the creator is severed upon the work’s release and new, unique relationships are formed with each reader/viewer/listener/experiencer.

It’s plain to me that Okorafor is referring deliberately to this idea in her title, and playing with it throughout the book. From protagonist Zelu struggling to control the story of her own life, as her overprotective/dismissive family seeks to box her in with their expectations, even after she becomes successful; to Zelu’s shock as her bestselling book takes on a life of its own in American, Nigerian, and world culture; to each book chapter’s narration switching from interviews of those close to Zelu, to Zelu herself, to robot Scholar Ankara, and back around the cycle; to the conflicts among robot societies after their creator-humans have died off — all of these shifts in perspective (all third person past tense) illustrate how stories always change, often drastically, depending on who is telling them and who the audience is. There’s also another major shift in perspective later in the book, but I won’t spoil that for readers.

About those robots: Zelu writes her “rusted robots” book when she’s in a bad place in her life; having stayed away from science fiction until now, when she no longer cares if her characters are relatable or not, and she wants to write something new and fresh. So the third chapter of Death of the Author: A Novel switches from Zelu and her problems to Ankara, a Hume (human-shaped) robot who revels in finding and retelling stories enough to become a Scholar. Ankara has strong desires to learn, to be heard, and to form connections, and sees that many robots who claim to be guided by logic alone are merely rationalizing their own preferences. Ankara has some noble goals, even if occasionally distracted from them, and I enjoyed following their pursuit in the occasional chapter-intervals between the human chapters. Ankara is a very relatable character, despite being a robot, because the challenges faced are essentially ones that humans face too: survival, tribalism, and the search for connection.

Zelu is a pleasure to relate to; she’s a very strong-willed woman, which her relatives criticize, but she’s had to be that to maintain any independence at all; her lover is sometimes frustrated by her but admires her strength. She takes sensual pleasure in food, bright colors, movement, and sex. She uses a wheelchair, and later makes a bold decision to try out cutting-edge technological mobility aids; I haven’t had to make any decisions like that, but of course any human being is just one major accident or disease away from dealing with disabilities (beyond garden-variety disabilities like having to use glasses or take maintenance medications). And Zelu’s struggles to reconcile her family’s Yoruba and Igbo traditions with her own aren’t anything I’ve had to deal with, but anyone from a big family, or even a smaller family with strong-willed members, can relate to family arguments.

I don’t know much about Nnedi Okorafor beyond her other books I’ve read, but a cursory search shows that she is a Nigerian-American who became paralyzed at age 19 and relearned walking with a cane. I’ve seen Death of the Author: A Novel called her most autobiographical book, and obviously she brings her wealth of experience to it. But it’s a mistake to think of this book as only that. She also has great wealth of imagination, and empathy; I adored this book’s breadth of ideas, and multiple perspectives, and experiments with structure. I loved every minute I spent in Zelu’s world, and the Rusted Robots universe, and I highly recommend this book to everyone.

Content warnings: Ableism, sexism, and whitewashing/erasure by characters and cultures, although negatively portrayed by the narrator and author; family squabbling; violence; attempted genocide by fictional (or are they?) characters.

Disclaimer: I received a free eARC of this book from the publisher for review, via NetGalley.