Along with stories by Stephen King, cinematic horror is largely responsible for introducing the weird and terrifying to me and a generation or two of teens. For years my friends and I sought horror films both good and bad, and we heard that particular macabre whisper calling us to the most unhinged and obscure among them. The memorable ones have been those whose reputations have created anticipatory trepidation equal to the thrills of watching the movie itself. The cursed production history. The banned content of unfathomable realism. The haunted film. Horror built around such themes of its visual representation proves popular, from Apollinaire’s “A Good Film” to Suzuki’s Ringu or American Horror Story: Roanoke.

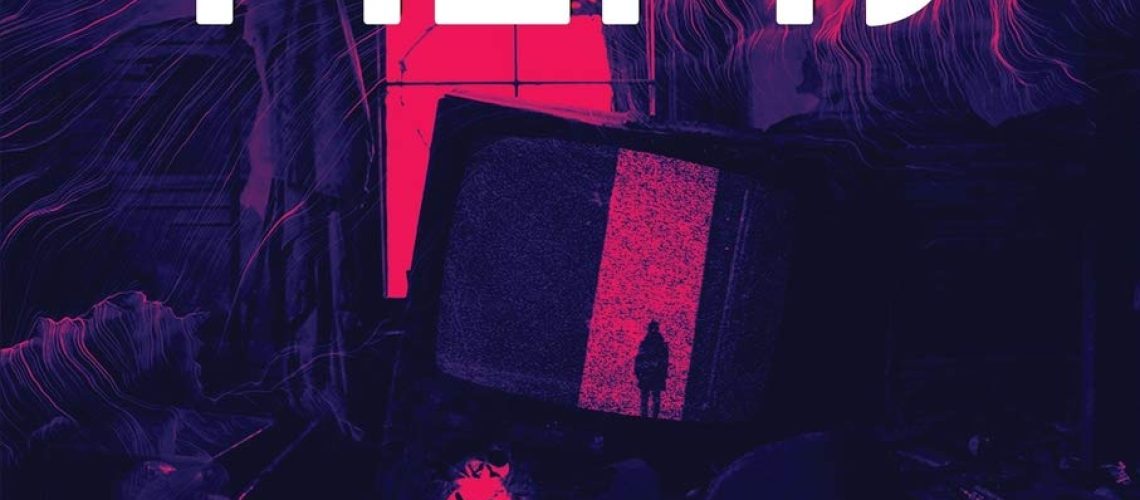

Ironically, written explorations of horror in visual media have a stronger impact on me than the those relayed through a screen medium. An excellent recent example would be Marisha Pessl’s Night Film. The announcement of the Lost Films anthology from Perpetual Motion Machine Publishing therefore really excited me. Comprised of nineteen stories with an introduction by Max Booth III (co-editor with Lori Michelle), it is one of the strongest collections I’ve read, with several potential standout favorites for readers from both established and new authors.

The collection begins strongly with the delightfully titled “Lather of Flies” by Brian Evenson, a creepy story that hit all the right notes with a horror film fan like myself. In it, a Ph.D. candidate in film studies obsessively pursues a print of a rumored film made by a cult director. Evenson has his protagonist stumble in that uncertain realm between truth and folklore in search of an esoteric experience, no matter the cost. With a plot that literally deals with a ‘lost film’ Evenson’s story perfectly sets up the theme of the anthology for readers, even without a direct reference in Booth’s introduction.

The bar of quality gets set even higher with Gemma Files’ novella “The Church in the Mountains”, with its balance of ominous style, layered characterization, vivid prose, and captivating plot. The young female protagonist of this story journeys home upon the death of her mother to face the grips that history and blood has upon her, all while trying to clarify vague images of a film she recalls from her childhood about a young woman journeying home for a funeral. The disturbed feeling created through this meta, self-referential element makes Files’ story haunting through multiple regards.

Another two personal favorites appear in the last third of the collection, “Stag” by Kristi DeMeester and “Things She Left in the Woods” by Jessica McHugh. McHugh’s story creates an air of disquiet around familial conflict, past trauma, and the present-day search for a missing child. While these are familiar horror themes, she takes them in interesting directions for a compelling conclusion. It really demonstrates the range that she has as an author. Similarly, DeMeester’s story is one of the best I’ve read by that author. Like the previous two stories discussed, it again features family discord, and like “The Church in the Mountains” it also deals with stifling control exerted by religion. But “Stag” ups the level of ‘disturbing’ with the pubescent protagonist’s feral attraction for a deer’s head in her living room. While each story forms non-essential connection to the visual-medium theme of Lost Films, McHugh and DeMeester enhance their plots with possessed TVs or haunting events imprinted onto videotape, respectively.

Roughly half of the stories in Lost Films are solid entries that I greatly enjoyed, even if they didn’t hit as many varied points for me as the previously mentioned titles. “The Fourth Wall” by Kev Harrison is a perfect example of such a story. A camgirl checks herself from getting too close to a client, but then is frightened to discover his dreams on the other side of the world manifesting in her physical reality. Although not complex, it serves as a perfectly entertaining and atmospheric bit of horror. Chief among all in this class of stories, however, is a back-to-back pair with plots involving film showings. “A Festival of Fiends” by Brian Asman imagines a film festival among killers, with entrants trying to outcompete one another in artistry and shock. “I Hate All That is Mine” by Leigh Harlen features a filmmaker who shows a short film at screenings and to friends, with each showing increasingly visually and emotionally disturbing. Each of these stories thus explore the theme of creativity in interesting ways. “The Thing in The Side Room” by Dustin Katz employs a similar element of filming horrific scenes, but in this case as part of a prank program to capture the real reactions of strangers.

“The Cosmic Atrocity” by Andrew Novak spins an existing example of ‘creepypasta’: a lost episode of The Simpsons. Rather than adapting the “Bart’s Death” story, Novak instead imagines something even more horrific: a lost series finale with lots of menacing Krusty the Clown, who a young child begins seeing everywhere. Two other stories similarly use such examples from reality as a jumping off point for something new. Bob Pastorella references R. Budd Dwyer’s on-air suicide in “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida on 8track”, bringing up the conflicting fears/desires that compel us to watch things that are disturbingly traumatic or macabre, like the faux reportage in the Faces of Death series. The collection ends with a novella by David James Keaton, “The Fantastic Flying Eraser Heads”, that references the ‘Mandela Effect’ (among other examples) to explore the eeriness between memory and reality. Keaton’s story is a decent close to the collection, but would have worked better for me as a shorter work. The penultimate story, “The Fabulous and Tormented Life of a Serial Extra” by Chad Stroup, would have made an even better closer. The plot of Stroup’s story features a man trying to discover the story behind a mysterious extra who appears in several horror movies. It could have served as a good bookend with the plot of “Lather of Flies”, even if Stroup’s ends up being far less sinister.

Two of the stories in Lost Films also stand out from the others in being less horrific, although still with touches of darkness, and both still good. The novella “Archibald Leech, the Many-Storied Man” by John C. Foster begins as something akin to a mystery or thriller, with an enigmatically fascinating protagonist. It then turns to in what I might call dark sci-fi meets portal fantasy. Though good, it seems like it is only a part of a larger work. The poignant “Ghost Mapping” by Eugenia Triantafyllou takes a look at haunting loss in a manner that is more melancholy than menacing, making it an appreciated break from the sinister undertones that dominate the rest of the collection.

The final taxonomical class of the collection encompasses stories that contain some measure of stylistic or narrative experimentation. Though more daring, they didn’t always work for me, particularly “Don’t Turn Around” by Thomas Joyce, a short piece written in the second person that tries to capture (or convey) the jump scare allowed in horror through the visual medium. Two stories are told in reverse, with “Daddy’s in a Snuff Film” by Kelby Losack using the ‘rewind’ of VHS tapes as a mechanism and “Famous Last Words” by Izzy Lee successfully using simple reverse narrative to illustrate bad decisions going exactly the way someone’s intuition warns them about. “Elephants That Aren’t” by Betty Rocksteady joins other stories here in exploring the familiar themes of memory and creativity, this time with weird little childhood drawings of smiling, tentacle-legged elephants. Ashlee Scheuerman structures “Teeth and Teeth and Teeth” around alternating campus security log entries and descriptions of their security camera recordings in a plot that involves the discovery of a lot of — you guessed it — teeth. A few of these stories will merit an additional read to glean more from them.

Illustrations by Luke Spooner perfectly complement every story on their title pages in stark black. Reminiscent of the flowing lined ink of Stephen Gammell’s iconic drawings in Schwartz’ Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark series, Spooner’s work looks creepily unique, rather than derivative. Lost Films is a ‘sequel in spirit’ to the 2016 Lost Signals, which was themed around audio horror. I’m eager to go back and read that now, and I hope any other horror fans out there will also enjoy either collection.