“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there” — L.P. Hartley

The conceptions and misconceptions of what medieval life was really like influence our perceptions of who we are as people, and the fiction and worlds that we create. There is a real struggle within certain sectors of the SFF genresphere about the fiction based on the world within what I call the “Great Wall of Europe”, fantasy with the viewpoint and a setting firmly grounded in conceptions of what Medieval Europe was like. Be it George R.R. Martin’s Westeros, or Kate Elliott’s Wendar and Varre, or a hundred others, Medieval Europe is, for a lot of writers and readers, THE setting to base their fantasy upon. However, many other writers get basic facts about Medieval Europe unintentionally wrong, further accentuating and perpetuating stereotypes and misconceptions about the Medieval world and mindset when they plug those misconceptions into their fiction, and those misconception are reinforced as misinformation about the real Medieval Europe.

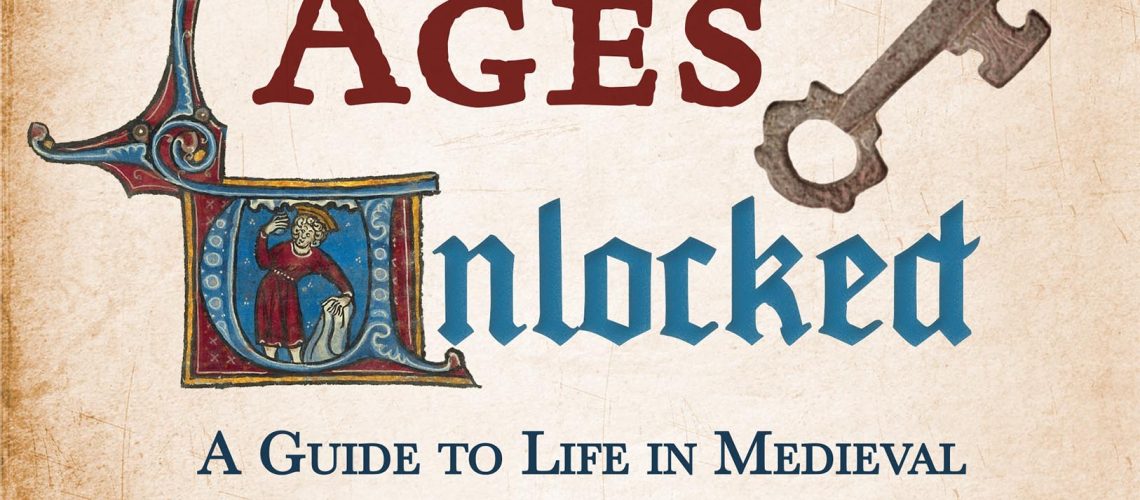

What was day to day life in Medieval Europe really like? Where can a reader looking for the real-life day to day life look for reliable information? Where can a writer wanting to avoid common misconceptions go? The Middle Ages Unlocked: A Guide to Life in Medieval England, 1050-1300, by Gillian Polack and Katrin Kania, aims to be a general survey history of the subject. Instead of Kings and Queens, nobles and high officials, the flow of history and the narrative of events through time, the authors look at different facets of Medieval life in Western Europe, particularly and specifically England.

The book covers a variety of topics. From religion to government, from the calendar to how people spoke, and how they measured things, the book provides an overview of every phase of medieval life you can possibly think of, and many that you would never have considered prior to picking up the book. For instance, a lot of Christian marriages took place on the Second Sunday after Epiphany in mid-January because of a long period in the calendar year leading up to Christmas where the Church did not permit marriages to take place. People in England and the rest of France mocked the Bretons for their belief and hope for the return of King Arthur (which is really the original heartland of the King Arthur legend, not England!). In the midst of the information, presented in an entertaining fashion, there is a large supply of these little bon mots and notes that turn the book from merely a textbook recitation of facts into an entertaining treatise on Medieval Life. Readers fearing a dry textbook tome should instead expect an often witty and funny volume that looks unflinchingly at the past.

The book does an excellent job in showing, in context, what the roles and status of women were really like. Women’s role and life in eras earlier than our own are a touchy, argumentative subject in SFF circles, when efforts to show the diversity and nuance of women’s life in earlier eras are seen by some as being revisionist or wrong. The authors stick to the evidence and the knowledge we have to show just what women did, how they behaved, and how they got along.

A delight and surprise, and something I didn’t consider when picking up and reading the book, is how the authors interweave and interlace the role and life of the Jewish population in England in the medieval era. If anything, the false stereotypes of the role of Jews in society in Western Medieval Europe are even more ingrained in our culture than the false stereotypes of the role of women. How did the small, thriving Jewish populations and communities of England in the Medieval Era prior to the Edict of Expulsion (1290) get along? The book does an excellent job in comparing and contrasting Jewish life with the life of the Gentiles in whose midst they live, and although the book itself does not discuss such historical events, it sparked in me a curiosity about the aforementioned Expulsion, of which I was not previously aware.

The Middle Ages Unlocked is excellent for any adult reader looking for a window into this era of history, not the historical events but what the day to day existence was like. It is especially useful for readers and writers who want a starting point to what medieval England was *really* like, top to bottom. Writers who want a basic idea of what this world was like, either to write in it directly, or to write in a fantasy world based on Medieval England, will find it immensely helpful in getting the basics down, and more besides. I learned a lot about facets of medieval society I had never considered before and I enthusiastically recommend it on that basis. Readers curious about what the world of Medieval Europe was like at the end of this period, in France, should then go on to the more narrative-based A Distant Mirror by Barbara Tuchman, which looks at the life of a 14th century French noble, Enguerrand de Coucy. Now having read Polack and Kania’s work, I have a much firmer grounding in medieval life to understand the work in which Coucy dwelled.

0 Responses

I purchased this book recently and it has been a very good read so far. I have not finished it yet.

Is this the sort of work that qualifies for Hugo Best Related Work ?

Gillian Polack is a science fiction author, as well as being a historian.

So many fantasy novels are based around a pseudo-medieval world, which was what sparked my interest in this book.

Its written by a Fantasy/SF author, and its certainly very useful for F/SF. And “best related work” tends to be whatever people nominate–so by those stars, it IS eligible.