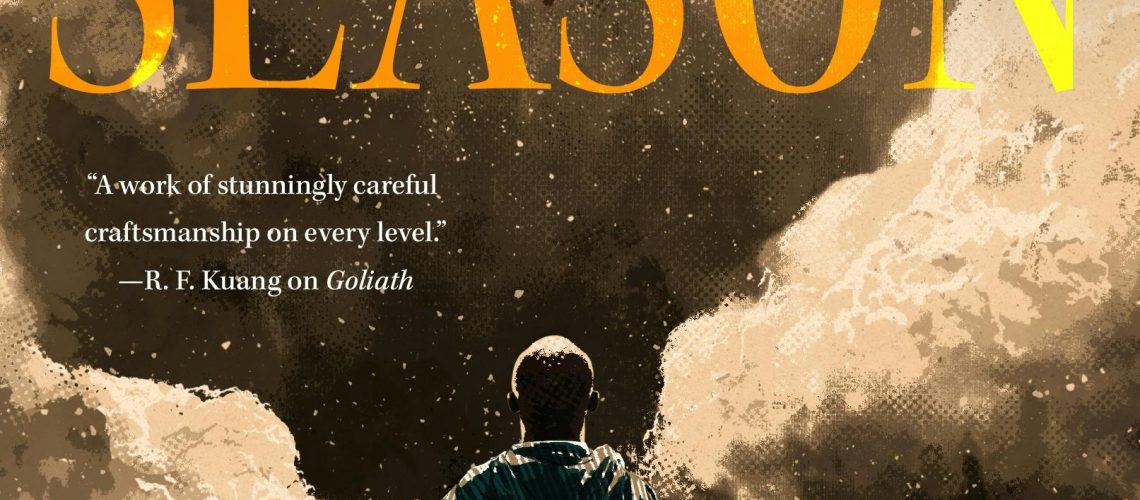

The publisher’s tagline for Tochi Onyebuchi’s Harmattan Season calls his novel “hard-boiled fantasy noir: Raymond Chandler meets P. Djèlí Clark in a postcolonial West Africa.” That’s fair, but it’s also very much its own thing. Some noir tropes in the novel are familiar: The protagonist is a struggling, world-weary private detective; he’s in an uneasy relationship with the police; the city has layers of money, power, class, and corruption; and an initial mystery turns out to be much more complex and wide-reaching than it initially appeared. Some elements have a lot of resonance for anyone who’s experienced or read about postcolonial African history. Even the most surreal fantastic elements of the book end up being employed in ways that eventually make some sense. But despite some familiar elements, their combination and development is unique and engaging. I wouldn’t quite call Harmattan Season an easy read, but it absolutely kept me interested throughout, and I was entirely satisfied with the ending.

In a recent Skiffy and Fanty interview with Shaun Duke and me, Onyebuchi said he was introduced to detective fiction during a college class. After gaining attention and awards with speculative YA fiction including Beasts Made of Night, Riot Baby, comics and video games, the nonfiction (S)kinfolk, and his first adult SF novel, Goliath, he said he wanted to try something different, less impenetrable and more “sneakily complicated” where the reader could follow along, so he returned to his old love of crime/noir. I haven’t read his prior work, but Onyebuchi certainly succeeded in making Harmattan Season approachable for me. It starts out pretty mysterious, of course, with the limited third-person present tense perspective as the narrator tries to figure out what crime is even happening, let alone what’s behind it all, but that’s just detective fiction for you.

Although things start expanding and shifting pretty rapidly, the opening of the novel is fairly typical for a noir detective novel: A woman steps into the protagonist’s place and asks for help. Less typical is that she’s already wounded; after he hides her, and the policier search his place, she’s gone from his closet.

Right, that’s policier, not police. I picked up some vocabulary while reading this book, some from context and some from Internet searches. Policier is easy to figure out, along with some other French words from this unspecified country’s colonial influences (although the past is still present here in many ways, such as the introduction of loans, which formerly had been illegal under local leadership and now dominate many people’s lives, including the protagonist’s, and the fact that French people are still moving here and taking the best jobs). Some of the words from the indigenous dugulen people’s language are harder to find, but that didn’t slow down my reading once I accepted that those would just have to come through via context, just like unfamiliar made-up words in any fantasy or science fiction.

The Harmattan of the title is a word with West African origins, “from or akin to Twi haramata” (according to Merriam-Webster), meaning a dry, dusty, seasonal wind. It can be hard to endure, and it can bury and erase places and people, but at least in this novel, it can also be seen as an opportunity for renewal and even rebirth. If you don’t have markers of the past anymore, you’re not as bound by its restrictions, and you have more choices for your future. And at least it’s not the wet season.

The book’s protagonist/narrator, Boubacar, can certainly use a reset, as can his troubled homeland. He has a very uncomfortable past, as a veteran traumatized by his past (what’s happened to him, and what he has done), a present where he’s barely scraping by (and merely tolerated or even mistrusted as a deux-fois man of both French and local heritage), and a future with dim prospects. He’s more or less frenemies with an old army buddy who’s now a policeman, and there’s a woman who lets him run an unpaid tab at her shisha house, but he doesn’t have any real friends.

Later on, he does acquire an ally of sorts, an urchin who offers to help him acquire information. The kid claims to be assisted by a gang of cronies, and it’s never clear whether this is true; meanwhile, Bouba doesn’t inform him that he has no money to pay for this help, so they’re both sort of scamming each other. Somehow, as they work together and keep getting thrown together, they come to rely on each other. Watching their interactions was the most fun part of the book for me.

The female characters aren’t deeply characterized and sometimes seem inexplicably drawn toward the protagonist, whom many might view externally and simplistically as a loser; however, that’s a trope commonly seen in noir detective fiction. There’s so much else going on in this novel that I was giving this aspect a pass, and then Bouba started asking more about people, not just events, and then the final chapter elevated everything. What Onyebuchi did with that was really lovely.

The fantastic elements start in the fourth chapter, when the missing girl re-enters the plot in an inexplicably surreal way. Bouba soon finds out that she’s not the first to have undergone this mysterious phenomenon, and later, it happens to a lot of people (and objects) at once, not just one at a time. The provincial government attributes this to terrorism, and now everyone in the city (who’s not rich) is in trouble, under a crackdown. Could the events be related to an upcoming election? Is it possible that things will change for the better or get much worse?

Since Bouba can talk to people that the police can’t (and the army investigative unit won’t), and he even gets answers sometimes (although sometimes he gets beatings instead), he keeps asking questions, in hopes of resolving the situation, or at least understanding it. He finds himself under uncomfortably greater scrutiny than ever before, and eventually moves from asking questions to taking direct steps.

Getting to know Boubacar and his city is really interesting; his past and its past slowly unfold as the mystery progresses, and the social commentary not only enhances the mystery, but eventually helps it to progress to a resolution. The fantastic elements are not explained, but in the end, they don’t seem much more surreal than life itself in modern times, with all its complications and unexpected turns. What’s most important is that Bouba persists and eventually moves from endurance to action. I ended up being really happy with Harmattan Season, and I highly recommend it.

MacMillan is releasing Tochi Onyebuchi’s Harmattan Season on May 27. Preorder here: https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250782984/harmattanseason/

Content warnings: Killings, mass attacks, body horror, colonialism, systemic police violence, racial discrimination/oppression, trauma flashbacks.

Comps: Midaq Alley by Naguib Mahfouz (although post-British colonial, not post-French), Red Harvest or The Glass Key by Dashiell Hammett, and “L’Hôte” (“The Guest”/”The Host”) by Albert Camus.

Disclaimer: I received a free eARC of this book for review from the publisher via NetGalley.