Since her birth, Zhu Yi has lived in her family’s ancestral house, and has taken its comforts for granted. Now, as she grows up, Yi begins to notice how atypical the Zhu family blessings are compared to the nearby small settlement where she attends school. Where her classmates struggle with lacks of basic needs, her family lives with resources aplenty. The Zhu house provides. It has always provided.

Ashley Deng gracefully reveals the climate-dystopia setting in her novella Dehiscent as seen through Yi’s eyes. Despite relative well-being compared to her peers, Yi laments the daily irritations of temperature fluctuations from too cold to too hot. Comfort is relative, and the revelation of this opens up a chasm of guilt in the young girl. Yi decides that she needs to share some of the abundance that the Zhu house provides. Despite warnings and aloof explanations from her parents, Yi starts to wonder how and why the ancestral home has provided for the Zhu family for so long, even with the ecological devastation that has disrupted previous civilization. Yi’s burgeoning conscience and curiosity lead her to the attic, the only part of the Zhu home she is forbidden to go, and the dark cost behind her family’s advantages.

I’ve only had the opportunity to read one other book from Tenebrous Press’ line of New Weird Horror novellas, Tim McGregor’s Lure, but the quality of that and now Ashley Deng’s Dehiscent makes for a strong argument to read more. They each masterfully employ the novella format to provide entertaining and disturbing horrors that blend sub-genre, make significant societal observations, and provoke reader reflection.

Dehiscent has a form of New Weird that combines eco-horror with what might be considered cozy horror, despite unsettling themes of the prison that can form from the recognition of privilege while feeling powerless to change it. With rich, quiet atmosphere and an exceptionally compelling and realistic, empathetic protagonist, Deng lifts a mirror to our current lives to reflect a fantastic image of how divisions of humanity would continue. The themes might not be new, but the premise of the powers of the Zhu house is. And Deng raises both truths and questions from those themes in perfectly compact fashion around this fictional horror.

The Zhu house plays in the novel almost like a character in itself, a living entity. Deng describes its structure as an architectural mixture of Chinese and Western styles, separate additions to the home through the history of China rather than a cohesive or even hodgepodge blending. While the themes of privilege, its associated guilt, and its dangers remain dominant in Dehiscent, cultural themes of the influence of Chinese and Western traditions on Yi, the Zhu family in general, and the surrounding settlement also become secondarily explored.

Though quiet and largely psychological, there are moments of physical horror and gore in the novella. There are bodies. While never scary, Dehiscent certainly plays with creepiness and the irony of uncomfortable truths underlying maintenance of personal comforts.

Meaning ‘open’ or ‘accessible’ in the broad sense, the adjective dehiscent also holds specific biological definition. Deng provides these at the very start of the novella: 1) the spontaneous opening of plant structures to release spores, seeds, etc.; 2) a reopening of a wound or tear of tissue in animals. The word serves as a fascinating title for the novella, matching paradoxical dualities in the central themes of the story and Yi’s desire/condition. Undeniably weird, Dehiscent also has a remarkable intelligence and keen observation of human complexities and imperfections.

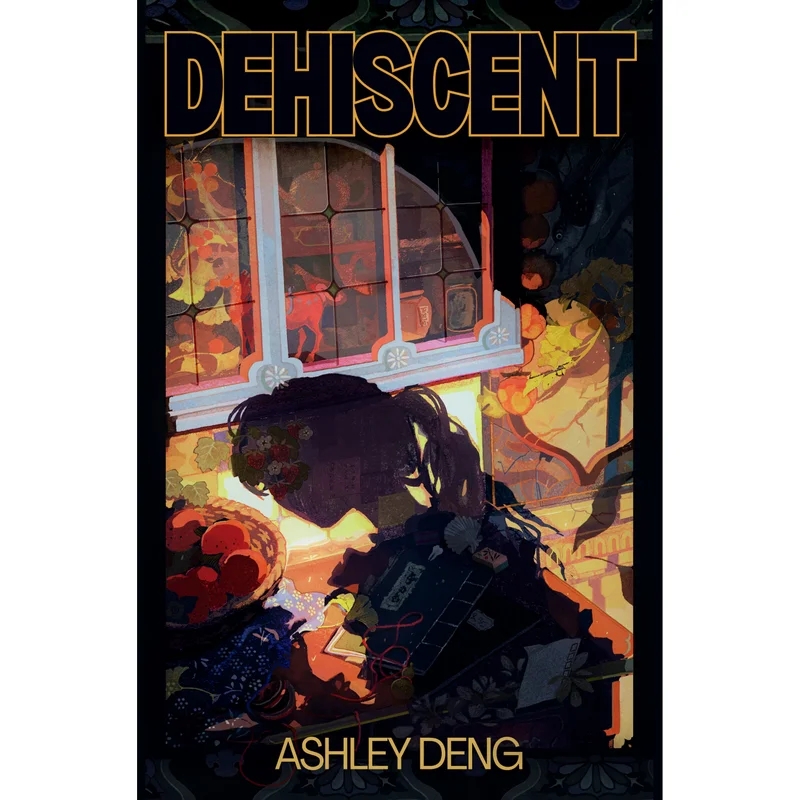

A final point of note: Those who appreciate the cover illustration for Dehiscent by Ivy Teas will be pleased to discover that the novella also includes additional artwork within the text that enhances the atmosphere Deng creates.