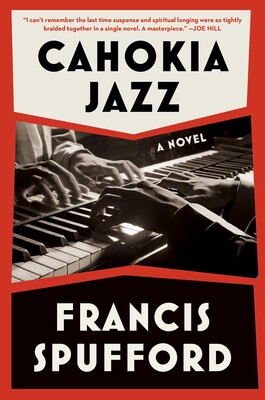

Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford recently won the Sidewise Award for Alternate History, presented at the Glasgow Worldcon. Spufford won acclaim in 2010 for Red Plenty, a fusion of history and fiction, and won numerous awards in 2016 for his historical fiction novel Golden Hill. This is the first book of his that I’ve ever read, but it certainly won’t be my last. I loved Cahokia Jazz’s blending of noir mystery, mysticism and religion, worldbuilding, action, and as signaled by the title, music.

The protagonist is Joe Barrow, a takouma (Native American, in our world) named after the town where he grew up in an orphanage, never learning a word of Anopa, the lingua franca of indigenous people along the Mississippi in this world, until he arrives in Cahokia, the capital city of the state of Cahokia, carved out in this universe from the states of Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Illinois. In our world, European diseases killed off about 90 percent of the Native American population; here, a weaker version of smallpox, variola minor, didn’t kill nearly as many people, so there are a couple of other indigenous-majority states in the Union, as well as an independent Republic of Deseret. In our world, Cahokia is an archaeological site near St. Louis; in Spufford’s alternate universe, Cahokia is a vigorous metropolis where takoumas, taklousas (African-descent people) and takata (European descendants) rub shoulders – often with friction.

Barrow, a drifter through life, recently came to Cahokia because his takata war buddy, Phin Drummond, found a job there a few years after the Great War and got one for his pal, too – so now they’re policemen, and not just patrollers, but detectives on the Murder Squad. (It appears this was via some kind of deal, since the squad’s captain is not overburdened with scruples.) Barrow usually just acts as the muscle and lets Drummond do the thinking, but after a man is found dead on a skyscraper rooftop, in an apparent re-enactment of a bloody Aztec sacrifice, Barrow finds himself unable to accept easy answers, and starts doggedly looking beneath the surface of things.

Barrow’s momentary independence of thought is bolstered and sustained when the unofficial royalty of the city, a descendant of Aztec princes although no longer claiming the title, says that he, too, wants the murder solved, not just scapegoated. So Barrow finds himself moving far above his usual station, interviewing industrialists and top-level mobsters along with religious extremists (a few people still believe in the old Aztec ways, although many takoumas follow a syncretic fusion of native faiths with Catholicism), going from hovels to exclusive clubs to speakeasies; some violent objections arise to the waves he’s making.

Various power-players exploit the rising tensions or try to defuse them as the city comes to a boil; meanwhile, Barrow is pursued by reporters, a few women start paying attention to him, and a band leader tries to persuade him to drop this cop life and pursue his true self as a jazz pianist. Barrow doesn’t know what he is at heart, and what he wants keeps shifting as he keeps finding out things about how his adopted city works and what his place in it may be.

I loved how Spufford showed readers his alternate world through Barrow’s eyes. Some info-dumps for the newcomer come from Drummond, the prince, and others, but often the reader gleans clues via subtle details, just a few sentences here and there, plus differing viewpoints portrayed in rival newspapers’ headlines. It turns out that land is not privately owned in Cahokia; everything is leased from the town, which is one of the sources of friction with Eastern capitalists; also, women play a much larger part in political decision-making than might be assumed at first.

The worldbuilding, the plot, and Barrow’s character development in Cahokia Jazz are wonderful, but I must also praise the prose that occasionally rises near poetry. Word choices always feel vivid and evocative, never unclear although often elliptical as Barrow struggles to divine hidden meanings, but sometimes the language is just beautiful, and I have to pause to appreciate it.

Thanks to the elevated construction site, with the whole thing perched on the brick embankment running slantwise across Grant Square, it had to be less heavy than Penn, with more glass and steel in the walls and comparatively slender stone piers supporting the vast glass dome overhead. But what it lacked in mass, it made up in light and color. The dome was a stained-glass sun, and the real sun outside threw dramatic lines of brightness and shade angling down onto the floor through the soaring windows, and across the floor, thanks to the colors in the glass, floating blobs of red and blue shifted constantly on pale stone, dark mahogany benches, the suitcases and hats of travelers, so that to get to the booking windows you waded through an imaginary meadow.

Everything about Cahokia Jazz is satisfying. Many things turn out differently than Barrow or I expected, but after the dust settles, they feel almost inevitably right, too. For the reader who’s at all interested in reading mysteries, alternate histories, diverse viewpoints, or following the development of an unsettled, initially almost indeterminate character who ends up making hard choices and taking terrible risks, please check this one out.

Content warnings: Murder and other violence, Klansmen and other bigots, and sexual harassment.

Comps: The Yiddish Policemen’s Union by Michael Chabon.

Disclaimers: None – thanks to my local library!