When Thomas Hobbes called the life of a man “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”, he could easily have been referring to the life of an Orc. Since their humble beginnings as song-croaking goblins in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, these dim-witted, often Cockney-speaking brutes have grown well beyond the Professor’s intent; they have seized a place of their own in the annals of Fantasy. While some fans will never see them as anything other than sword fodder and servants of this Dark Lord or that, others have embraced them as noble savages, maligned and misunderstood – and worthy of their own books.

Long have I pondered the question of how mere spear-carriers in the epic drama of Tolkien’s legendarium captured the imaginations of so many readers. Tolkien himself was conflicted about the origins of the Orcs. In the published version of The Silmarillion, Orcs were created from captive Elves: “Yet this is held true by the wise of Eressëa, that all those of the Quendi who came into the hands of Melkor, ere Utumno was broken, were put there in prison, and by slow arts of cruelty were corrupted and enslaved; and thus did Melkor breed the hideous race of the Orcs in envy and mockery of the Elves, of whom they were afterwards the bitterest foes.” Later, the Professor recanted this and never really settled their origins in his mind (though his last notes on the matter seemed to intimate that Orcs were bred from captive Men).

But in the years after the publication of The Lord of the Rings, Orcs spread through the fantasy sub-culture via the medium of role-playing games. They became ubiquitous; every fantasy RPG – and even a couple of science fantasy games – had their own version of the Orc. It was only a matter of time, really, that they returned to their roots in fiction. While Mary Gentle’s Grunts (Bantam, 1992) was the first post-Tolkien novel to cast Orcs in a prominent “starring” role, it was the publication of Stan Nicholls’ Bodyguard of Lightning (Gollancz, 1999) that signaled a shift in how Orcs were perceived. Nicholls sought to redeem the Orc, to rescue them from their role as arrow magnets and present them as a fully-realized fantasy race. With Bodyguard of Lightning and its sequels, Nicholls’ succeeded in making his Orcs more human than the Men in his story.

Which, of course, brings us back around to the question of why. Why Orcs? What is it about them that causes certain readers to sympathize with their plight? More than mere minion, the Orc has morphed into a powerful symbol: the ur-Barbarian, the Other who lives and thrives on the edges of polite society. The Orc is cunning, savage, hard to kill. The Orc represents chaos and change; it threatens the status quo and offers nihilism, dystopia, and rapine as valid alternatives. To a writer, there is much to explore within the context of the Orc.

But there also needs must be a thread of humanity pervading their character. We may not like them, but we must be able to understand them in order to manifest sympathy for them. The Orc must think like Us, to some degree. He must feel and react like Us. Listen, for example, to the speech of the Uruk-hai near the end of The Two Towers (Ballantine Books, 1983):

“Can’t you stop your rabble making such a racket, Shagrat?” grunted the one. “We don’t want Shelob on us.”

“Go on, Gorbag! Yours are making more than half the noise,” said the other. “But let the lads play! No need to worry about Shelob for a bit, I reckon. She sat on a nail, it seems, and we shan’t cry about that. Didn’t you see: a nasty mess all the way back to that cursed crack of hers? If we’ve stopped it once, we’ve stopped it a hundred times. So let ‘em laugh. And we’ve struck on a bit of luck at last: got something that Lugbúrz wants.”

“Lugbúrz wants it, eh? What is it, d’you think? Elvish it looked to me, but undersized. What’s the danger in a thing like that?”

“Don’t know till we’ve had a look.”

“I iz more cunnin’ than a grot an’ more killy than a dread, da boyz dat follow me can’t be beat. On Pissenah we jumped da marine-boyz an’ our bosspoles was covered in da helmets we took from da dead ‘uns. We burned dere port an’ killed dere bosses an’ left nothin’ but ruins behind. I’m Warlord Ghazghkull Mag Uruk Thraka an’ I speak wiv da word of da gods. We iz gonna stomp da ‘ooniverse flat an’ kill anyfing that fights back. We iz gonna do this coz’ we’re Orks an’ we was made ta fight an’ win!” – Graffiti on Warlord Battle Titan wreckage, found by Dark Angels at Westerisle, Piscina IV.

And between those poles, the portrayal of Orcs in fiction run the gamut: Stan Nicholls’ are quarrelsome and violent, but functionally no different than their Human enemies. Author Morgan Howell, in his Queen of the Orcs trilogy (Del Rey, 2007), presents Orcs as Noble Savages patterned after the Iroquois of central New York. And on it goes. Though superficial elements such as appearance differ, every Orc who has thus appeared as a protagonist in fiction is imminently recognizable to readers. The answer to why, then, is echoed in the 146th aphorism from Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil: “He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.” We write the monster, but what we’re really writing is ourselves.

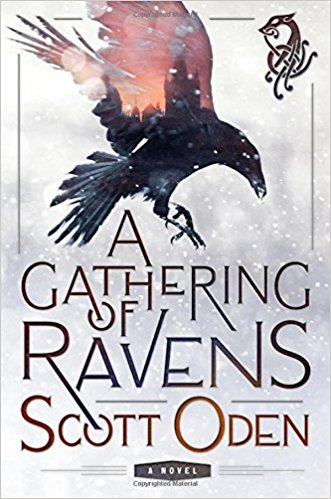

SCOTT ODEN was born in Indiana, but has spent most of his life shuffling between his home in rural North Alabama, a Hobbit hole in Middle-earth, and some sketchy tavern in the Hyborian Age. He is an avid reader of fantasy and ancient history, a collector of swords, and a player of tabletop role-playing games. His previous books include Men of Bronze, Memnon, and The Lion of Cairo. His fourth book, A Gathering of Ravens, has just been released. When not writing, he can be found walking his two dogs or doting over his lovely wife, Shannon.