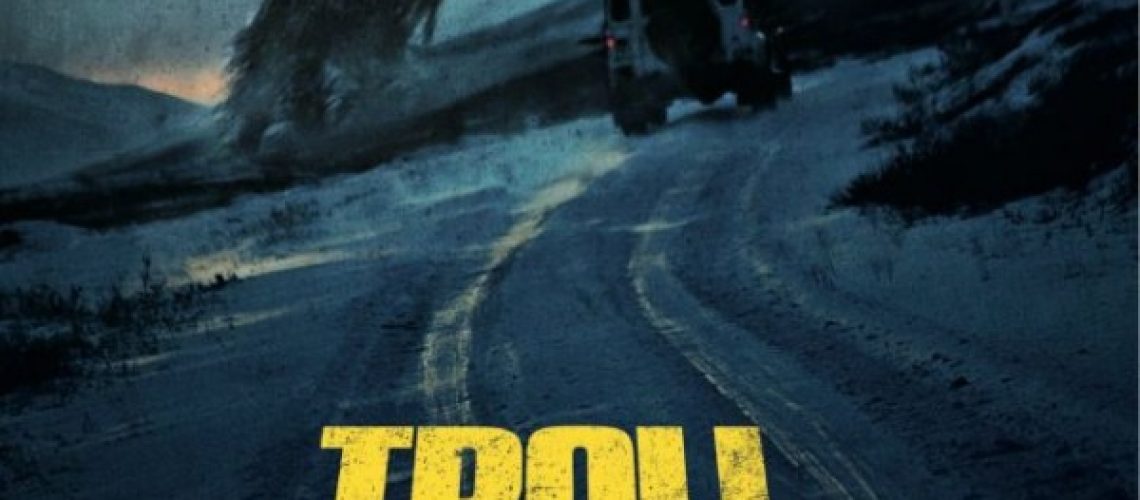

Trollhunter (2010)(Trolljegeren in Norway) is André Øvredal’s most popular film, though it is, I’d argue, sorely overlooked by American audiences. Originally released in October 2010, the film was eventually transplanted to U.S. audiences via the Sundance Film Festival in January 2011. The premise is fairly simple:

Under the guise of presenting secret footage, Trollhunter follows a trio of student journalists who arrive in the mountains in order to interview and document the actions of a mysterious man named Hans who locals suspect is illegally killing bears. In their attempts to catch the man in the act, they follow him and discover that Hans is actually a trollhunter, protecting the borders between human and troll territories with a UV light gun and other clever amenities. Invited to ride along, the trio document Hans’ journey to determine what has caused a recent series of violent troll events, only to realize that they’re in over their heads.

Borrowing heavily from the found footage tradition and Scandinavian folklore, Trollhunter tackles the “myths are real” trope with a seemingly Scandinavian gravitas. The film’s use of trolls and the myths that surround them is handled with an amusing seriousness, affirming some beliefs (sunlight and Christian blood sniffing) and shattering others. The troll “facts” and scenes are playful on the one hand, but also quite serious and brutal on the other, including a solid dose of tense action amid straight documentary fair. If the film is strongest in any particular arena, it is in its troll sequences, particularly the climactic ending, which I won’t ruin for you here. Though the visuals are clearly on the lower end of the scale, they are used sparingly to lend more credibility to the “realism” of the narrative, and to keep attention not on the trolls as mythic objects, but on the character’s reactions at any given moment. This is a factor which is sometimes lost on directors today as bigger and flashier films become the norm, even when the budgets clearly don’t allow for it. Here, there’s no flash; everything, it seems, is measured.

Trollhunter is also a beautiful film, despite its focus on found footage. The shooting locations in Western Norway are hard to describe, though I must say that they made me want to visit the country for myself. The film also uses Norwegian scenery to great effect, putting action in wooded areas where visibility would naturally be low, thus adding suspense, or in grand, snow-covered “deserts” where the intensity of the landscape matches the intensity and terror of the action. I tend to think that scenery is sometimes lost in films these days, but here, the landscape plays a crucial role in the film’s dynamic approach to the found footage format.

The film also relies quite heavily on this format, providing a fragmented documentary feel which shows Øvredal’s deft direction. The desire to keep this feel from start to finish is, I think, admirable, as the realism facilitates immersion and the seriousness suggests a deliberately limited framing. Unlike films like District 9 (2009) or Cloverfield (2008), whose narratives aren’t as cleanly integrated into the format, Trollhunter never strays from its documentary imaginary; the narrative and the format, here, are integral to one another, such that removal of one necessarily breaks the other, particularly since the artificiality of the film’s structure only works if the format remains stable. The flaw with the found footage format, of course, is in its tendency to artificially limit the potential for in-depth performances — often in the service of presenting “real” performances, to varying degrees of success. Here, the focus is not on character development or dense performances — the most emotional scene occurs after a character’s death and is unnecessarily short and seemingly forgotten in the performances that follow. Otto Jespersen (Hans), Glenn Tosterud (Thomas), Johanna Mørck (Johanna), and Tomas Larsen (Kalle) each handle the restrictions of the format well enough, but the film never quite seems to escape the trappings of that format to produce something more than a gimmick — albeit, a solid one at that. The performances just aren’t what’s of interest to the filmic space, and so much of the film’s narrative drive comes from the complication of the world-with-trolls and the documentary-style examination of Otto’s job (a la something like Werner Herzog’s Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (2010) — albeit, more withdrawn).

The film’s weakest point is in its comedic relief. Perhaps this is a matter of translation — one comedic tradition to another — but I found much of the film’s tone to be wholly serious even in its absurdities. If it is a comedy, it is certainly of the driest sort, despite the fact that this is a movie about a guy who hunts real life trolls (Jespersen, it turns out, is a well-known Norwegian comedian). At times, it includes the sort of dark humor one might find in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, but much as some of my students don’t find the humor in one of Faulkner’s greatest work, I didn’t quite laugh out loud while watching Trollhunter either. Even when the film gives in to the desire for bodily humor, it is done in a way that is tonally serious, rather than deliberately farcical. Much of this tone is created by the film’s found footage format, which seems to narrow the focus on a satire of the ironic or exaggerated sort, but not necessarily of the deliberately mocking or wholly critical kind. This is not to suggest that the film is never funny, such as when it rewrites Norwegian industrial history to incorporate troll monitoring, but the impression I got from the trailer that this film was intended to be funny didn’t have enough traction upon an actual viewing.

Regardless, I do think Trollhunter is a fascinating film, if for no other reason than it handles the found footage format well and treats its subject matter with enough rigor to give it a sense of realism that is necessary for immersion. It’s certainly an enjoyable film, so if you’re looking for a fantasy film that draws upon real world folklore with a side of adventure, this is one worth watching.

—————————————————-

Directing: 4/5

Cast: 3.5/5

Writing: 3.5/5

Visuals: 3.5/5

Adaptation: NA

Overall: 3.625/5 (72.5%)

Inflated Grade: B (for adventure and decent handling of the found footage format)

Value: $8.50 (base on $10.50 max)

——————————————

A (World) SFF Film Odyssey is an extension of my personal mission to watch and review every science fiction and fantasy film released in 2010. All of the non-US titles will be reviewed/discussed/maimed on the Skiffy and Fanty blog as part of the World SF Tour. The rest can be found on The World in the Satin Bag. You can find out more about this project here.

4 Responses

Definitely watching this sometime. Been meaning to for a while.

It’s definitely worth seeing :). Netflix!

Has “Rare Exports” made it onto your list?

It is on the list, yes, though we reviewed it for Torture Cinema a long time ago (see the link at the top of the page for Torture). I’ll re-watch that film at some point 🙂