To say that reviewing Nightcrawler (2014; dir. Dan Gilroy) is a difficult task would be an understatement. Nightcrawler haunts the viewer like something out of Poltergeist (1982; dir. Tobe Hooper). It’s the kind of experience that I find impossible to forget, not simply because of its focus on Los Angeles’ late-night chaos but also because its examination of that life is in so many ways uncompromising and disturbingly logical. Talking about such a film without blathering on endlessly becomes a difficult task indeed, which may explain why this review is so focused on a single element: Bloom.

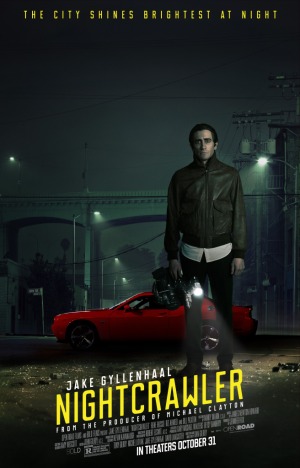

Nightcrawler follows Louis Bloom, an eccentric small-time thief who literally steals his way into the “nightcrawler” business in Los Angeles after witnessing a “nightcrawler” taping a car accident (Bill Paxton). Determined to “make it,” he begins selling to a low-rated local news station and sets out to dominate the market at any cost.

Part of what makes Nightcrawler both uncomfortable and enticing is Gyllenhaal’s performance as Louis Bloom. Nuanced and chilling, the character is the embodiment of controlled chaos, seemingly always on the edge of exploding, and yet never really reaching that moment. There’s a sense here that Bloom is not quite “there” with the rest of us, practiced in his emotions. Alien. This is obviously partly fed by the film’s almost exclusive focus on Bloom, such that we know about this underlying chaos before anyone else does. However, it is difficult not to watch Gyllenhaal’s counterfeit smile without always anticipating an explosion that never quite arrives; others might explode, but Bloom does not — as if having practiced the demeanor of a sympathetic character without actually becoming one. Uncomfortable though Bloom’s character may be, his regurgitation of business-oriented self help and his frequently calm demeanor are difficult to turn away from. Bloom is at once friend and nightmare, mentor and corrupt boss. He is the resolution of a paradox.

Bloom is also mobilized throughout the film as a comedic-satire-turned-foul. Though Bloom may be at times almost comical, his behavior is quickly understood as a pattern of manipulation. This manipulation is distinctly capitalistic, driven by Bloom’s obsessive need to understand the industries in which he works so he can better turn that system against itself — in the process, he hopes to turn the tables in his favor. His early attempts, though failures, are as much about Bloom’s instability as they are about the language of socioeconomic groupings, from rental security to construction to, eventually, the eponymous “nightcrawler” profession. Each time, Bloom’s speeches become increasingly pointed, researched, and driven.

In this respect, descriptions of the film as being about a “young man desperate for work” are inaccurate. Bloom isn’t desperate so much as opportunistic, willing to manipulate the discourses of capital at every turn, initially using narratives of hard work, perseverance, etc. to worm his way into these micro worlds and then putting them into action as if that was what he meant to do all along. The narrative progresses by reinforcing these cultural functions in distinctly unethical fashion, as its various characters increasingly challenge the boundaries between ethical news and legal news. Nobody is safe from this. Indeed, Bloom makes sure of it by using industry knowledge to convince Nina (Rene Russo) to compromise her values; that he also uses his personal knowledge of Nina to manipulate her for personal favors should lend credence to the “crawl” in the title. As in skin crawling (you’ll know the scene when you see it).

The ethical element can also be boiled down to a single line, as Anthony Lane notes in his New Yorker review: “You’re going to show this?” The closer Bloom’s footage comes to lies, the more poignant the line — here uttered by Nina — as benefactors become facilitators. Bloom doesn’t simply record crime or violence; he creates it — first by manipulating the layout of a crime scene, and second by creating the situations which lead to such crimes. It is this progression which ultimately makes Bloom unambiguously depraved and the people who have fallen within his web equally so. Unlike Walter White, Bloom doesn’t change so much as become a knowledgeable, power-driven version of his earlier self. For that reason, Bloom is not unlike a capitalistic fairy tale taken from the pages of an Ayn Rand book, and the longer he is on screen, the colder the room becomes.

Watching this process occur on the screen is at once beautiful and internally terrifying. To say that Nightcrawler is a critique of contemporary capitalism and its impact on the corruption of the news is really to point out the obvious. But the true haunting lies in its characters, who seem unable to escape such systems because they are always already implicated within it. They are the sheep, and Bloom is the wolf who devours from within.

Uncomfortable though this movie may be, I cannot recommend it enough. Nightcrawler is well worth the emotional roller coaster, and it certainly commands multiple viewings.