Welcome to the latest installment of my comics review column here at Skiffy & Fanty! Every month, I use this space to shine a spotlight on SF&F comics (print comics, graphic novels, and webcomics) that I believe deserve more attention from SF&F readers.

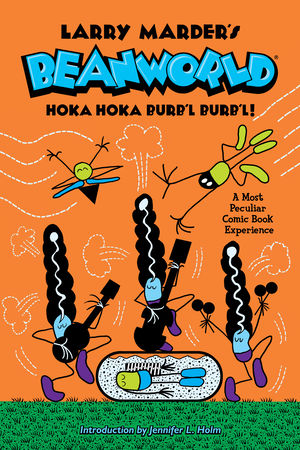

This month, I’d like to direct your attention to the original graphic novel Beanworld Book 4: Hoka Hoka Burb’l Burb’l! (This review contains spoilers!)

Created, Written and Illustrated by Larry Marder

Editor: Philip R. Simon

Published by Dark Horse Books

Beanworld Book 4: Hoka Hoka Burb’l Burb’l! marks a return of one of my very favorite independent comics after a long absence (Book 3 was published in 2009), and a very welcome one.

This is an incredibly challenging series to synopsize. It’s sometimes described as an ecological romance, or ecological fantasy. Beanworld creator Larry Marder has always described it as “a most peculiar comic book experience”. He’s also said that the setting is neither science fiction, nor fantasy, but I think that in fact it’s both: a richly-imagined and detailed place which is itself a pivotal character in the story, and a story where both the inhabitants and the reader learning to understand the place is a key part of the narrative.

Beanworld is, in short, the story of a group of thinking beings – the Beans – who live in harmony with their natural environment, while they also learn about the laws that make their world function and engage in dynamic cultural, technological and generational innovation to develop new solutions to new problems that emerge when their balanced corner of the cosmos comes into contact with the bigger picture.

It helps if you understand Beanworld, as Larry Marder noted in the letter column of a long-ago issue of the comic, as being very much like the story of a legendary past, of the culture heroes whose genius brings a society the gifts that make life both livable and worth living – but told as those events unfold. I think of Beanworld, in this way, as being a lot like the El-ahrairah stories in Watership Down, but told from the perspective of El-ahrairah and Rabscuttle.

It’s also about the role of art in society. And the life-cycle of the bean plant.

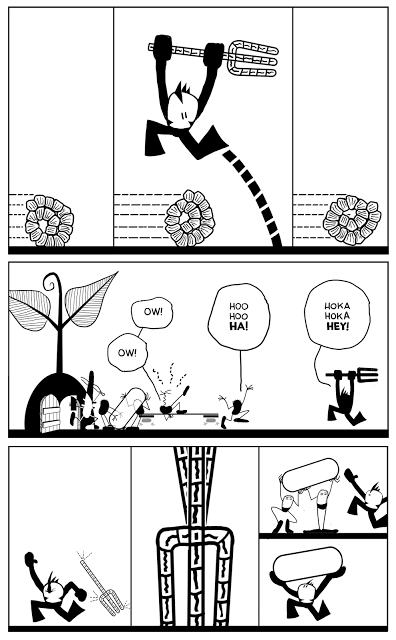

Yeah, in Beanworld, the art seems simple. The characters seem simple. The underlying ideas are rich and complicated and thought-provoking.

In this book alone, we learn more about the Beanworld’s musicians, the Boom’r Band, and the vital role they play in their culture; Professor Garbanzo, the inventor and problem-solver, works to try to understand the natural laws that underlie new discoveries; the youngest members of Bean society, the Cuties, continue to seek their destiny in the sky with the help of the backwards-talking Bean Heyoka; and weather comes to the Beanworld for the first time.

It really isn’t a place. It is, as Larry Marder has always said, a process.

Marder’s art remains perfectly suited to his story. It seems, as I noted above, deceptively simple, while actually being both highly engaging and nuanced. The Beans are tremendously expressive characters, and they and the iconic shapes that comprise their world convey a depth similar to, say, petroglyphs, or cave art – the seeming simplicity that actually reveals a deep understanding.

The writing is fun and the characters pop effortlessly from the page; Marder knows them well, and there’s so much joy for the long-time reader in watching these old friends simply be themselves.

That said, Beanworld Book 4 is not without its flaws. At points, it feels choppy and episodic, with focus shifting between characters in unsatisfying ways. I suspect this is the result of its origins, as Marder himself relates with moving honesty in the Afterword, as a narrative comprised of elements excavated from a deferred, longer work that might have been smoother and more complete, which he had to put on hold after the death of his wife. With that in mind, I’m still hopeful that the next installment, whenever it arrives, will include a more focused, deeper dive.

This is also, and this is not a flaw so much as simple fact, not the best jumping-on point for new readers. My girlfriend, who isn’t much of a comics reader and doesn’t know Beanworld at all, picked up the book and read the back cover copy to me aloud:

“Hoka Hoka Burb’l Burb’l…The Boom’r Band discovers a previously unknown healing power hidden deep inside the Chow. This triggers a chain of events leading to a visit from the Windy Songsterinos…”

Then she turned to me and said, “None of those are words!”

Marder does his best to give new readers an overview, but while the brief introduction clarifies terminology and establishes the world and the characters, it can’t provide emotional context. If you don’t have some history with the characters, there’s much less impact in realizing that you’re about to – finally, OMFSM finally I’ve been waiting twenty-five years for this! – be told the Secret Origin of the Boom’r Band.

There are three and a half previous Beanworld books (the book that sometimes gets called Beanworld Book 3.5 is a collection of shorter, full-color comics; it’s not a great jumping-on point either). Books 1 and 2 compile the original run of the comic. Book 3: Remember Here When You Are There!, was the first book published by Dark Horse to contain all-new material. Beanworld Book 1: Wahoolazuma! contains Marder’s earliest comics work and it’s not quite as polished and a little bit tonally out of sync with the rest of the series.

I recommend starting with Book 2: A Gift Comes!, which contains the latter half of the original run of the comic. The Beanworld is clearly defined, the broader narrative is starting to unfold, and the characters and concepts are effectively established for potential new readers.

But now for a question, a bigger and more serious one, that troubles me: Does Beanworld appropriate Indigenous culture, specifically Hopi culture, in its use of elements of that people’s visual design and spiritual traditions and practices?

My provisional answer to that question is… I don’t think so? Marder has always been open about the influences on Beanworld, and they are many. Pop art and Cubism and Silver Age comics and botany and mythology and many other things. Hopi design and spiritual traditions are among those influence, and I think they’re important ones. But Marder is clear about his sources, and how they’ve inspired him. He does not claim at all to be representing actual Hopi practices, Hopi art, or Hopi people, and he’s encouraged readers to learn more about the real people and real culture that are part of his inspiration.

Ultimately, I’m not the right person to answer the question. I don’t have the right, via either lived experience or expertise. If any Indigenous people, especially Hopi people, would like to share their thoughts, I’d welcome that.

So, setting that question aside pending more reflection and information, I’m very happy with this book. Beanworld is back, the Beans are back, there are answers to old questions and new questions to puzzle over. And Sprout Butts are still sassy.

It’s not a place, it’s a process, and one that I encourage you all to explore.

Acknowlegements and Disclosures: I would like to acknowledge that Toronto, and the land it now occupies, where I live and work, has been a site of human activity for 15,000 years. This land is the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat and Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. The territory was the subject of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Iroquois Confederacy and Confederacy of the Ojibwe and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes. This territory is also covered by the Upper Canada Treaties. Today, the meeting place of Toronto is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island. I am grateful to have the opportunity to live and work in the community of Toronto, on this territory.

I don’t have any personal or professional relationships I’m aware of with the creator or publisher. I purchased my own copy of the book.