As these words are written, there is yet another debate in science fiction over who the Hugo Awards and Worldcon are for, and their very legitimacy given what has happened with the Chengdu Worldcon. [See Cora Buhlert, among others, for details: https://corabuhlert.com/2024/01/21/the-2023-hugo-nomination-statistics-have-finally-been-release-and-we-have-questions/]

Arguments over the Hugo awards and Worldcon are nothing new, and were at the heart of the business of the “Rabid and Sad Puppies” several years ago. The 2021 Worldcon had two Hugo administrator boards resign, as well as the Chair itself. And now, the 2023 Worldcon and the Hugo Awards have had the greatest controversy yet, with people (including myself) mysteriously declared Ineligible and nomination and voting statistics that are inexplicable.

And when confronted by this, there is a stratum of old guard who do not want any change, and in fact are resistant to any change to Worldcons and the Hugos. A stratum of people willing to excuse what happened with Chengdu or to just bury and deny and stonewall.. There are even suggestions that, for example, site selection for Worldcon should now be restricted to known attending members.

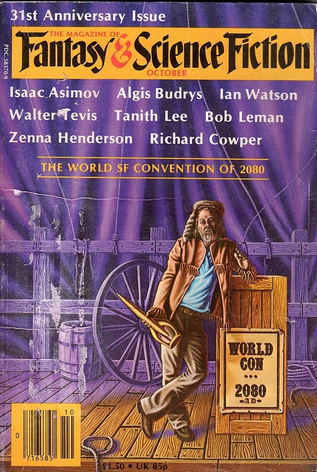

I want to come to recent events in another way. All of this reminds me of a story that I want do a deep dive on: “The World Science Fiction Convention of 2080” by Ian Watson (published in 1980). This is a short, very inside baseball story of Worldcon, Worldcon fandom and science fiction, and it is quite revealing. Buckle in.

The story starts like this:

“What a gathering! Four hundred people — writers, fans and both magazine editors — have made their way successfully to these sailcloth marquees outside the village of New Boston…”

Before I discuss the themes of the story, I just want to admire the worldbuilding in that sentence. At the time of the writing of this story (1980), aside from the Worldcons not held in the US, Worldcon attendance was several thousand. 400 is a big drop. “Both magazine editors” is another clue that things really are amiss. Sailcloth marquees? Village of New Boston? Combined with the title, the reader can get the sense immediately that in 2080, things aren’t all that great; we’ve more than lost a step. There has been a Collapse of some sort.

The next paragraphs describe a definitely fallen world, describing “Moslem Pirates” and “Indian arrows” and other dangers that have taken away members of the small but vibrant SF community. The author talks about his new novel, The Aldebaran Experience, briefly and modestly, and then launches into the highlights of Worldcon. In the diminished 2080, the traditions of Worldcon are a little changed. There is but one film, Silent Running, a print shown by sunlight, and without a soundtrack. The auction (a staple these days particularly of fan funds) is of increasingly rare books from before whatever set this world back to the 19th century. There is a publisher party. And then there is the “Banquet” (the Hugo awards used to be a banquet and then the awards).

Jerry Meltzer’s “Some things do not pass” hits the two themes of the story, the first being finding joy in that since science has stopped its “Research and probing”, science fiction has “come into her own” and that SF folk are “Homers and Lucians” once again because “science is a myth; and we’re its mythmakers”. Given the timing and the time in which this was written, plus the description of the books being written, it feels like a paean to earlier science fiction. I am reminded that Viking had landed on Mars several years before this story was published, and if there was any hope that Mars might have held life, it was ended by Viking.

The romance of interplanetary adventure had more or less been squashed. I can see Watson’s story lamenting, through the GOH speech about the closing of horizons of science fiction, but now, in this diminished world of 2080, those diminished horizons are gone. This theme of accuracy and plausibility in science fiction is a whole other kettle of fish that could merit an essay of its own. But I also see this in terms of the Puppies and their wish that science fiction return to an earlier mode of science fiction, to the hazy golden age of science fiction as they saw it. Their attempts, first by logrolling, and then by outright attempts at manipulation of the process to conquer the Hugo Awards, eventually turned into an attempt at destruction, but I remember that some of those folk at the time merely wanted to turn the clock back on what kinds of SFF were the ones honored at the center of fandom. And I see it in the old guard of SF Fans who do not want to change with the times, who want things the way they always were. Fans who are unwilling to make the changes needed to keep the legitimacy of the Hugos themselves.

But it is the end of the Guest of Honor Speech, the end of Meltzer’s speech, that really makes it resonate for today, if the first theme did not.

“We really own the stars now. We really do. Never would have done, the other way. Dead suns, dead worlds, the lot of them…The dense suns of the Hub are all ours. All.” If this was not clear that this is the driving theme of the piece, the last lines of the story has our narrator echo these worlds to his companion “We own the stars. You and I.”

From the perspective of 2024, this second theme feels at weird odds with the actual facts of the story and the facts on the ground of science fiction. I read this story as wishing for the “good old days” of science fiction, when Worldcon was a few hundred people, when everyone knew each other, and science fiction was just for *them*. When slow fanzines were the way that a few science fiction writers, readers and fans kept science fiction a burning light in the darkness. When science fiction was small, and isolated, maybe even persecuted a bit. When science fiction was a club, and its fans had that and themselves, and the rest of the world could go hang.

However, it’s wishing for a time already past in 1980, never mind today. By the time this story was written, not only was Worldcon being attended by a couple of thousand people, as previously mentioned, but Star Wars had emerged, and science fiction was moving to conquer the world. Fandom and who are science fiction fans was expanding by leaps and bounds. Science Fiction was changing, rapidly and was continuing to change. The door to the club of Science Fiction was slowly starting to open, and many more people wanted to come in and become part of science fiction fandom. New voices, new perspectives, new ideas. There have always been writers, readers and fans who are not white Western men, but it was in the 1960s and 1970s that it became inescapable and undeniable that people of all kinds were in science fiction, as much as people might try. (The story of Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree Jr is illustrative.) To this day, though, there is still far too much pushback against the idea that they belong in science fiction, even as they are there and have always been there. They have always written.

Let me go back to that opening paragraph and look at it again. Moslem Pirates, Indian arrows, and the fact that even in a diminished 19th-century style that Worldcon is being held in (the remnants) of America is a parochial and racist point of view. Our hero is from Scotland and travels to New Boston by a variety of conveyances, and believes he will go to the next Worldcon several years hence in the “fishing village” of Santa Barbara. At the time of the writing of the story, there had only been two Worldcons not in the UK or North America, but it feels like those tentative steps are definitely slammed shut. Fandom is a North American and UK phenomenon in this diminished world.

But this mindset is even more insidious than it first appears. The Moslem pirates who killed Charmian Jones might have taken her back to a “seraglio” in North Africa. The odor of orientalism is undeniable and unmistakable in that phrase. The reader is given less in order to imagine the Indian badlands, but the same sort of racism pervades that idea, too. The story mentions, in a couple of words, “Army Induction centers” and “technophile citadels” as well, but the order, odor and framing of the threats is more than clear.

The Worldcon Convention of 2080 feels like wishing for the process of widening science fiction to be arrested, to halt and to go backwards. Even with the dangers and diminished circumstances of this post-Collapse 2080, there is a gauzy sense of nostalgic content in what science fiction and what science fiction fans are in this world. The story for me feels like an attempt, in 1980, to want to hold onto a vision, a model, a mode of science fiction that was gone by then, and would continue to evolve and change to this day. But to wish for an earlier time, to return things to an imagined golden past that never was what you actually thought it was, or to want to close doors, to decry people wanting to come in and become part of the process and make it more inclusive, more welcoming, more open to others, is reactionary, and I would argue, contra the narrator of this story, and contra Meltzer, it is against the spirit of science fiction.

Fans are NOT Slans. Fans are not a small substratum of special and superior people. Science fiction readers, writers and fans are people, people of all kinds, all stripes, all types. There are millions of fans now. To want to hold tightly onto science fiction and what have been seen as its core centralities (and that includes Worldcon and the Hugo Awards) is to be contrary to the potential strengths. This is as contrary to science fiction as to seek to turn the clock back and make science fiction in an earlier mode. To limit, constrain, circumscribe and enclose science fiction, be it in terms of theme, or whose stories and what stories are told, honored and awarded, or who can be and is a fan, is to weaken science fiction and its fandom. Even if that motive, even if the mindset is from a place of love and desire, trying to hold too tightly onto science fiction and science fiction fandom (and that includes Worldcon and the Hugos) is far more risky to its relevance and power than the alternatives.

To misquote Princess Leia: “The more you tighten your grip, Tarkin, the more science fiction will slip through your fingers.” The narrator of the story is wrong. He and his fannish friend do not own the stars. Those who would circumscribe science fiction and its fandom are wrong.

We ALL own the stars.

NB: If you want to read the whole story itself, its available in an ebook of Watson’s SF here:

https://www.amazon.com/Sunstroke-Other-Stories-Ian-Watson-ebook/dp/B00GVFQLG0/

One Response

Interesting find.

You made me go check this story out (surprised I could, wow). If I hadn’t read your take, I think I’d read it more as a response to 1970s science fiction, especially movie SF, from the new decade. Poking fun at the tropes and dire predictions that didn’t come true. With a bit of “we true fans will still be here once the new mass popularity wears off, doing this thing the way we did it before, when we had to walk ten miles to school uphill in deep snow.” (And, yes, stuff that hadn’t benefited from Edward Said’s popularity in academia ten years later. That it’s hard to not find in these old rags, even from currently still-favored olds. If Tiptree can be shoved deep in the trunk so quickly, not much will survive.)

Left me still curious about the nostalgic gatekeeping move you assume was going on in the story. (Though I’m not up on who did that then, or does that now except bits and pieces.) The author’s blog is full of reports from far-flung cons, reading, and travel, and historical bits about British SF estranged from US-centered fandom and the life in Spain. Not what I expected after reading your take. Now I’m really curious how this played to SFnF readers/ insiders in 1980.

(There’re some great typed and hand-edited letters from U.K. Le Guin on IW’s blog, well worth the effort of having gone to look. Did stoke nostalgia for the old fandom vibes, like the letters between LeGuin and “Star bear” do. As well as his spouse’s beautiful photographs of Spain and travels. Not a bad Saturday morning web digression. Thanks for the nudge.)

After thought, it’s interesting as future prediction, really. “The conversation” now occurs in such a ragged patchwork, thanks to the actual collapsing of print publishing’s old shell, and now of Web 3.0++, with the pandemic’s effects on the con caravan. Even if 2000+ show up here and there, the groups of 20-400 within that don’t really talk together much. And random things do keep most people out of the conversations and gatherings when they do happen. Awards are always an artificial slice, shaped by power moves if one kind or another. The survival of the fittest ‘whoever makes it to the physical location makes this year’s happening tick’ core of the story isn’t wrong about the battle over the means of production (of meaning). A current rewrite à la The Women Men Don’t See, and it’s follow-ups, would be interesting.

-Stars for Brainworms