The other day, I was exchanging a few thoughts with Shaun about film, the need to entertain, and the engagement of emotions versus the idea of a film that was a purely intellectual experience. This brought me to thinking about the same topic in relation to horror.

Some years ago, I read an anthology of horror tales that was a success in that the stories were skillfully written, but a failure in that few, if any, worked at all as horror. The reason for this was (what seemed to me) a misplaced desire to “transcend” the field (a subject for another time), coupled with a form of self-referential storytelling that worked fine in and of itself but prevented the reader from engaging emotionally/suspending disbelief/what-have-you. Let me add here that I intend no disparagement to a more writerly (as opposed to readerly) style — each has its strengths and particular uses. However, what this illustrated for me was the lesson that the more overtly self-conscious or metafictional a work, the less likely it would be to frighten its audience.

And after all, “horror,” as a descriptor of an artistic endeavor, is an affect (an effect as well, if one considers the ostensible goal of the work). The very name explicitly states the visceral engagement that is sought. Obviously, this does not preclude an intellectual engagement as well. But it does suggest that the former is the priority. One might even go so far as to suggest that the emotional hook is integral to the cerebral project — the mind’s more considered examination of the work being shaped by the initial emotional experience. A dark version of Wordsworth’s emotion recollected in tranquility, if you will.

Still, in the wake of the aforementioned conversation, I found myself approaching this question from a slightly different angle: trying to think of works that engage in a primarily intellectual form of horror. I immediately ran into problems of terminology and definition, and I haven’t come close to coming up with a satisfactory answer. What I am toying with, however, is the idea of works whose locus of horror is less in the terrible things that might (or do) happen to the characters, but rather the theoretical and conceptual implications of the story.

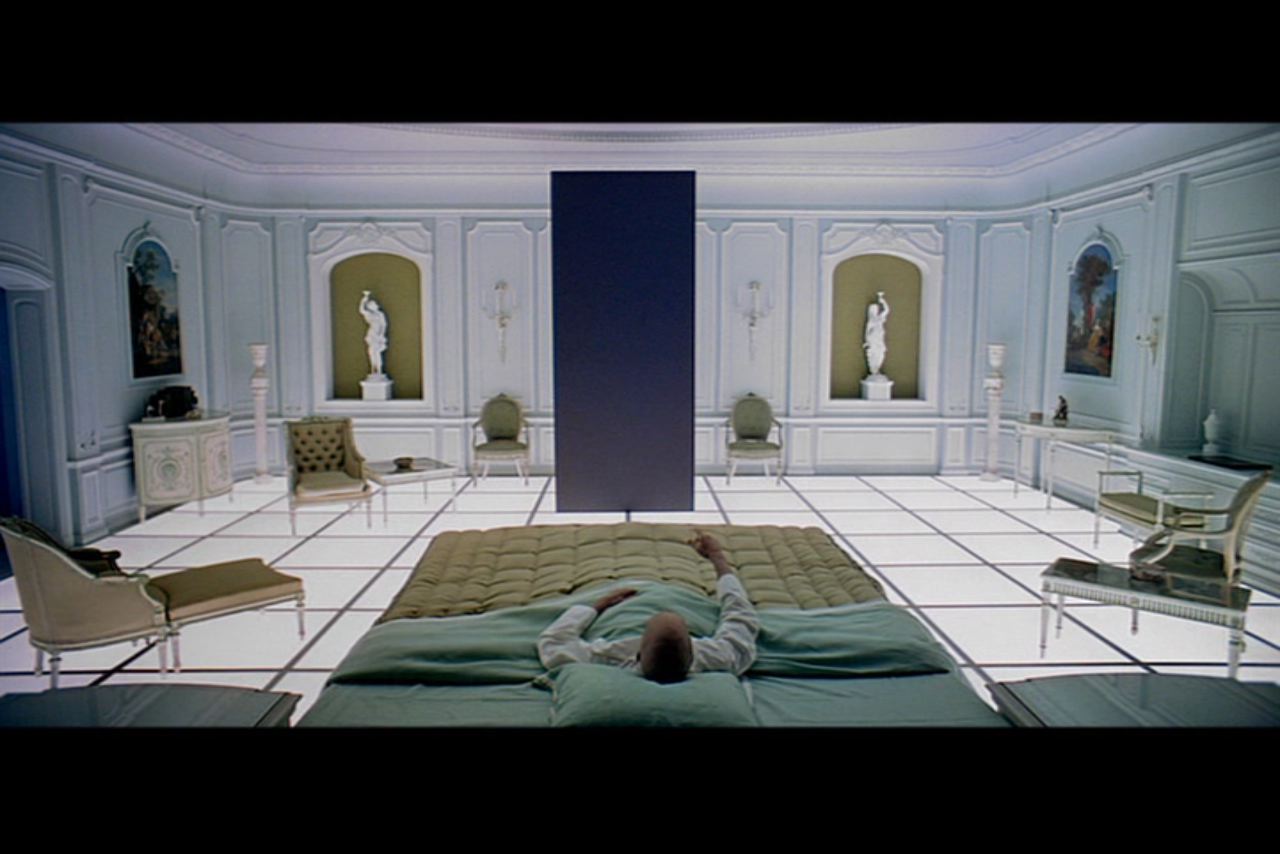

Two brief examples by way of illustration. In The Great Movies, William Bayer argues that 2001: A Space Odyssey is as much a horror film as it is SF. “There are many moments of horror in 2001,” he writes, “but perhaps the most overwhelming one is the picture’s vision of man, a creature that mutates from the spontaneous, frightened, wretched, clumsy, murderous apes of the ‘Dawn of Man’ section into the controlled, unemotional, sterile, competent, dehumanized technologists of the moon visit and the Jupiter mission. Somewhere in between, civilization came and went.” It came and went, of course, in that famous jump cut from club to satellite, a cut whose implications sink in long after it has passed. We might also discern horror in the film’s vision of a cold, godlike intelligence manipulating human evolution for ends that remain obscure to us. The madness of HAL 9000 and the murders on board the Discovery appear to be in the service of a grand plan whose purpose we do not know, and thus the greater chill comes not from the deaths in and of themselves, but from the questions of motive and implications about the universe.

The second example is Georges Franju’s Les yeux sans visage (Eyes Without a Face, 1960). This is one of the most extraordinarily beautiful and poetic horror films ever made, and there is no question that it has a dramatic visceral impact on its audience (the surgery scene still makes people look away). One of the things that makes the film so unsettling, though, is its restraint, and its quiet approach to suffering and horror. As he commits atrocity upon atrocity in his attempt to restore his daughter’s features (destroyed in a car crash that he is responsible for, due to his domineering way of driving), Dr. Génessier remains calm, utterly convinced of his right to act as he does; he is free of melodramatics. His utter rationality speaks volumes about the society that empowers such a man, and so Les yeux sans visage chills us by means of the broader implications that we must think through, as well as through the immediate horrors it portrays.

In both cases, though, the cerebral is activated by the visceral. Is there such a thing as an entirely intellectual horror story? I’m not sure that there is. It seems likely to me to be a contradiction in terms. But I would be fascinated to be proven wrong.