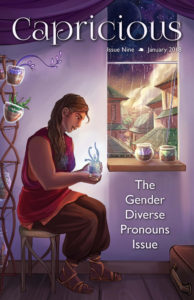

Capricious Issue 9 may have flown under your radar, but it shouldn’t have. Capricious is a speculative fiction magazine based out of New Zealand and edited by A.C. Buchanan, and Issue 9 is a special issue devoted to gender diverse pronouns, including singular they, common neopronouns (such as e/eir/em), and new pronoun sets created by the authors. I like that Buchanan chose the term “gender diverse” rather than “gender neutral,” since some of the stories in this issue feature more than two genders (which is awesome). The issue features a diverse array of genre tropes, and it spotlights two things I desperately want to see more of in SFF: inclusion of nonbinary gender identities, and experimentation and play with pronouns and gender systems. Here are my favorite stories:

“Ad Astra Per Aspera” by Nino Cipri

The opening story “Ad Astra Per Aspera” by Nino Cipri is an abstract, playful piece that begins with the wild line: “I’m pretty sure I lost my gender in Kansas.” Which is such a superb first line. Obviously, since genders are abstract social constructions, you can’t exactly “lose” your gender, simply speaking. But that doesn’t stop Nino Cipri from writing a funny story about doing just that. And beneath the playful, irreverent humor, Cipri somehow manages to seriously reflect on how gender can be nonbinary, complicated, and evolving. Also, Cipri’s story includes this fabulous aside:

(This is a placeholder for your judgment, even your disgust. What kind of irresponsible twit loses their gender? If you had a gender as nice as mine, you would have taken better care of it. Maybe you’re thinking that this might be some sort of millennial thing. All these millennials with their boutique and artisanal genders, and this is what they do with them?)

I still can’t get over the phrase “boutique and artisanal genders.” Can we, like, put that on a sassy coffee-mug or a t-shirt, please?

“Volatile Patterns” by Bogi Takács

Bogi Takács’ delightful work of science fantasy takes place in a universe that reminds me of Star Wars. There’s an interplanetary alliance of technologically advanced cultures, and there’s also māwal, a powerful quasi-magic underlying the universe that calls to mind the Force. The protagonist is Ranai, who feels like a mix between Sherlock Holmes, a Jedi, and a sophisticated cultural emissary. In this story, Ranai and their partner Mirun are called in to another planet to investigate social unrest that seems to be of a magical nature. Despite the obvious similarities to Star Wars, however, this story isn’t derivative—it isn’t about a war between between the alliance and a group of rebels. Instead, Takács’ story is driven forward by mystery, humor, warmth, cultural interchange, and political dynamics, and there’s also an exciting bit of action-adventure at the end.

Ranai uses they pronouns, and Mirun uses Spivak pronouns (e/eir/em). This makes me happy; it’s important when writing about marginalized people to both have stories that are directly concerned with challenges specific to their communities, as well as stories in which the protagonists just happen to have marginalized identities. “Volatile Patterns” is distinctly in the latter camp, which is what makes it so damn fun. This story is a space operatic science fantasy whose protagonists just happen to be nonbinary and neuroatypical. It’s stories like this that do important work in helping to normalize these identities. And here’s the best part: “Volatile Patterns” is actually part of a webserial that Takács has been writing called Iwunen Interstellar Investigations. On eir website, Takács describes the series as a “cheerful nonbinary trans couple solving magical crimes around the universe!” So if you like “Volatile Patterns,” you can go read more online.

“Sandals Full of Rainwater” by A.E. Prevost

If you’re a linguistics geek, you simply must read A.E. Prevost’s “Sandals Full of Rainwater.” In this story, a twenty-year drought pushes Piscrandoil Deigadis to immigrate from their native Salphaneyin to Orpanthyre. The plot is simple but compelling enough: Piscrandoil finds friends, falls in love, and looks for a job. None of those things are easy, which gives A.E. Prevost plenty of character-driven conflict to keep readers engaged in the story.

What makes this story excellent, however, is its approach to worldbuilding, language, and gender. Piscrandoil’s native country and language don’t have gender, socially or grammatically, but Orpanthyre has three genders. As A.E. Prevost explains in the author interview accompanying the story, “in Orpan, your perception of yourself and others is what determines which pronouns you use for yourself and for them.” The result? Orpan has forty-five pronouns, and A.E. Prevost actually uses those pronouns in the text. For example, a merchant tries to sell Piscrandoil an umbrella and says, “I’ve got a nice blue one that matches yunna skirt.” Later, a landlord turns Piscrandoil away, saying, “Not moun fault we’re full up.” The forty-five Orphan pronouns are confusing, even bewildering at times, but it works. My experience reading the story paralleled Piscrandoil’s experience immigrating to Orpanthyre and learning Orpan. Also, since the Orpan pronouns are mostly derivatives of English pronouns, the reading experience isn’t as confusing as it could have been. In fact, it often just felt like the characters were speaking with minor accents.

I actually found Orpan’s pronouns tons of fun—a brilliant reminder of just how inventive and inclusive SF literature can be, especially when writers critically engage topics in linguistics. After all, you can play with language and culture in fascinating ways when you experiment with pronouns. Pronouns can reflect gender (or lack thereof), they can differentiate between objects and people (e.g., it versus she), and they can reflect status or formality (e.g., tu versus usted in Spanish, or 你 versus 您 in Chinese). I’m personally hunting for a fantasy story that uses a unique pronoun set to refer to gods. And if “Sandals Full of Rainwater” whets your appetite for linguistics, then check out The Ling Space, a Youtube channel that A.E. Prevost works on that produces a bunch of fascinating educational videos on topics in linguistics. I’ve watched a few videos, and I’m hooked.

“Phaser” by Cameron Van Sant

The last story that I’ll highlight is “Phaser” by Cameron Van Sant, a funny, sophisticated story about the complexities of gender identity. I think it might be my favorite story in the issue. “Phaser” opens with Elizabeth coming out to her mom as a lesbian. Her mom then grounds her and insists she’s just going through a phrase. The story then accelerates into the realm of wild, science fictional tropes as Elizabeth is abducted by aliens and meets her future self: Z, a genderqueer college theater student who uses they pronouns. After Elizabeth and Z chat it out for a little bit, the story takes a sharp turn when another one of Elizabeth’s future selves shows up. I’m not going to spoil such a fun, surprising story—just go read it.

It’s a mark of Cameron Van Sant’s strength as a writer that “Phaser” stays grounded in Elizabeth’s POV even as we meet her future selves. Indeed, much of the story’s humor comes from juxtaposing Elizabeth’s teenage concerns with the perspectives of her future selves. Elizabeth worries about her relationship with her girlfriend Rose, her relationship with her mom, her future acting career, and of course her own identities. However, her future selves have mostly forgotten about Rose, and they have new concerns of their own. This juxtaposition creates humor, but it also gives the story its emotional and thematic weight. Elizabeth’s worries kept me emotionally invested, which is especially important in such a wild, trope-filled story. And Elizabeth’s fear of her mom being right, of Elizabeth merely going through a phase, engages the story’s most sophisticated theme: the complexity, instability, and evolution of our gender identities.

“Phaser” made me recall “Beyond 101”, a fabulous discussion about trans and nonbinary identities in SF (published by Strange Horizons in January). In that essay, Vanessa Rose Phin remarks, “It seems to me that there is only one kind of queer questioning story: a one-time event that works like an on-off switch. I modified my pronouns just this week. Again. I don’t expect I’m done with it. Where is the lifelong process?” I love “Phaser” because, beneath its silly, trope-filled humor, it actually portrays a lifelong process. As Van Sant reveals in his author interview, “I tried to portray a gender evolution that had to occur in order for the character to be their most authentic self … I wanted the narrative to show that it’s okay that main character did not come out ‘right’ the first time, and it’s okay that they experiment with their gender and made mistakes.” This is difficult to show because this sort of questioning, this ongoing critical interrogation of one’s gender identity, is often used against trans persons. As Katherine Cross notes in “Beyond 101,” trans persons are “forced into certain gendered performances in order to win conditional acceptance. In 2017 I still hear from trans girls who say that medical professionals, with power over their lives, doubted the sincerity of their transition because they weren’t feminine enough. This mentality stifles us all.” Some people may experience their gender as stable; for others, gender can be a process of becoming. Our society isn’t good at handling both those truths at once, and that’s what makes “Phaser” so awesome: it’s a wild, smart take on how gender identity can develop over the course of a person’s life. You’ve gotta check out this story, especially if your gender identity isn’t exactly a paragon of stability.

These four stories are my favorite. They have all stuck with me long past my initial reading. And if none of these stories interest you, then let me say that in the other six stories in Capricious Issue 9 you’ll come across dragons, ghosts, merfolk, the fae, artificially intelligent spaceships, and origami fauna.