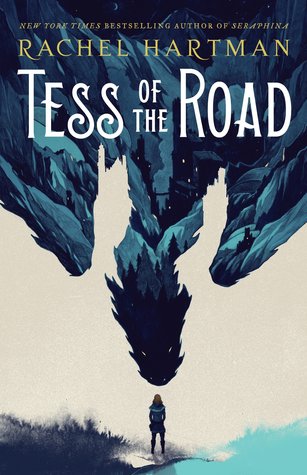

Tess of the Road by Rachel Hartman is a deeply affecting young adult novel that is part coming-of-age and part episodic road trip. It focuses on the eponymous Tess, a young woman who runs away from home to escape the restrictive life that is slowly smothering her.

Rachel Hartman is best known for her Seraphina duology. Tess of the Road is not only set in the same world, but Tess is Seraphina’s half sister. New readers don’t need to have read the previous series in order to read this book; it makes clear how the world works. However, Tess of the Road takes place after the events of Seraphina and Shadow Scale. Several of the characters from these books make cameos and I highly recommend reading them first if you are adverse to spoilers.

The story starts out with an episode from Tess’s childhood in which she, as a six-year-old, sets out to discover where babies come from. Having recently attended a family wedding, she knows it has something to do with marriage, or maybe kissing. Right away we can see that Tess is a free spirit, highly intelligent and very curious. She’s keen to discover how the world works and is not afraid to use direct experimentation to find out. It also sets up the world she lives in and, in particular, its restrictions on female sexuality. It points out the double standards in how men and women are treated. It also touches on the way in which women internalise these standards and begin to police themselves.

This opening is made all the more powerful by the contrast it forms with the first chapter. Tess is now seventeen and seems an entirely different person. The punishment from her puritanical mother and the restrictions of society make her work hard to push down her spirit and appear respectable. Thanks to Seraphina’s influence, she and her twin sister are now ladies-in-waiting at court but remain relatively low in the pecking order. Tess has focused all her efforts on securing an advantageous marriage for her sister so that the family can avoid poverty. When this is achieved, Tess hopes to begin living life for herself. However, these hopes are quickly dashed and so Tess takes matters into her own hands.

Although Tess sets out on an adventure, it’s not in any way romantic or epic. Indeed, in the beginning, she doesn’t even have a purpose, only a driving urge to get away. Instead, the focus is on the people Tess meets on the road and the effect they have on her (and vice versa). Told in close third person, it’s a very intimate story. In fact, the episodic nature of her encounters and the largely internal focus reminded me of The Long Way to A Small Angry Planet by Becky Chambers. However, there’s an additional layer to the structure, with parts of Tess’s backstory being told in flashbacks triggered by her encounters.

Sometimes these are literal flashbacks that are triggered. This is a book that will break your heart. It touches on a multitude of issues, including alcoholism, suicidal ideation, dementia, infant death, emotional abuse, emotional labour, rape and rape culture. It’s a lot to pack into one book. Not all of these issues are dwelt on for long and I would have liked a few of them to be unpacked further or resolved. However, the key issues are handled beautifully.

One of these issues is spirituality. A short way into her adventures on the road, Tess encounters a childhood friend. Pathka is one of the Quigotl, who are a kind of lizardfolk and poor cousins to the dragons who walk this world in human form. Pathka has been given a dream quest and is determined to find one of the seven World Serpents—the giant creatures who helped form the world, according to Quigotl legend. Tagging along fulfils a childhood dream for Tess, so the two set off together. Along the way they meet a variety of spiritual figures—some admirable, some abhorrent. The contrast was particularly striking between Tess’s mother and one of the nuns Tess meets. Tess’s mother is a bitter woman who became devoted to a particularly puritanical saint after she discovered her husband’s first wife—Seraphina’s mother—was a dragon. She uses scripture—and in particular scripture about the sin of women’s sexuality—as a weapon to take out her anger on Tess. She is emotionally abusive and seeks to control as much of Tess’s life as she can, viewing Tess’s own choices as mistakes. This is in contrast to Mother Philomela. The nun is the first person to try and understand Tess, aware of the ways in which this society treats young women. She pushes Tess to develop her own philosophy, to grow and learn. In this way, the story balances its depiction of spiritual women, rather than allowing them all to be painted with the same negative brush. I really appreciated the nuance.

Another issue is about anger and forgiveness. Tess is treated poorly by her family, even by those that mean her well. The world is hard on Tess, which makes her hard on herself. She doesn’t always deal with her emotions in a healthy way, but lashes out at others when she’s hurt. This may lead some readers to find her unlikeable, but I felt it made her relateable and I found myself rooting for her from the very first chapter. It also leads to a downward spiral, until Tess can find a way to forgive herself. This family dynamic is also echoed in Pathka and his daughter Kiku. Tess must come to terms with the fact that her friend makes a terrible mother (yes, mother. The Quigutl have some interesting gender dynamics at play) and that there are also some important lessons in their relationship that she can apply to her own situation.

This is not going to be a book for everyone. I’ve already touched on the difficult issues and the divisiveness of Tess as a character. Some readers may also find the pace a bit slow and the plot a bit meandering. It is, as I said, a very internal narrative, and some of the characters may seem a bit flat and only there to teach Tess some kind of lesson.

However, I found it a rich book, one that wears its feminism and its heart on its sleeve. I very much look forward to the sequel.

One Response