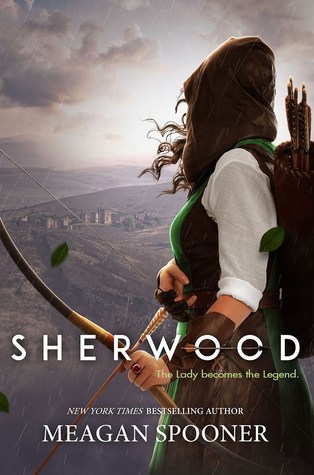

Lady Marian is left heartbroken when her fiance, Robin of Loxley, is killed in the Crusades. Already feeling constrained by society’s expectations of her as a noblewoman, she finds herself also increasingly struggling against the unjust laws and taxes levied against Robin’s people—her people in all but name. When she sneaks out one night to help the fugitive Will Scarlet evade Guy of Gisborne, she is mistaken for Robin and drawn into a double life.

This feminist retelling was everything I could have wanted. Marian doesn’t conform to traditional ideas of femininity. She has Opinions about the injustice she sees around her, but is smart enough not to be too vocal about it; she knows well enough that her voice will be ignored and that there is a limit to what talk will accomplish. She’s also uncommonly tall, is terrible at embroidery, has a head for figures and is a brilliant archer (natch). This makes it sound she’s Not Like Other Girls, and I feel she definitely skirts the line. However, the story belies this by showing how she’s supported by other intelligent women. Some of these women are more traditionally feminine, but, like Marian, are smart enough to know that speaking up will get them ignored (at best). Instead, they act strategically in an effort to support a more just world.

Marian is not without her flaws. Although smart, she’s also reckless and impulsive; while she holds the safety of her men in the highest regard, rebelling against being coddled as a lady means her sense of freedom manifests as a disregard for her own safety. And while she is also aware that being a noble means she has an obligation to be a voice for those she governs, she’s also blind to her own class privilege. Even when she has learned about this flaw and turned it into a tool against Guy of Gisborne—in potent combination with blindness to gender privilege—it still trips her up from time to time, with dangerous consequences.

Although Robin dies in the prologue, he still has a presence throughout the book. His relationship with Marian is told in flashback from his perspective. This allows the reader to see them grow up together and to see Marian from another point of view. Robin’s voice also haunts Marian after his death. It makes for a powerful meditation on grief. It also raises questions about legacy: does Marian truly remember Robin as he was or is she twisting her memories of him to justify her actions?

Guy of Gisborne makes for a surprisingly sympathetic antagonist. Having been caught and tortured in the Crusades, he was sent home with a facial disfigurement. This immediately had me bristling, wondering if this was going to be an ableist shortcut to highlight his status as a villain. Instead, very little weight is placed on this aspect of him, more serving as an explanation as to why he’s not also absent at the Crusades. For the most part, the injury doesn’t repulse those around him and he’s even portrayed as a figure of desire in places. His stiff, awkward manner is the partly the result of his common upbringing and partly the result of his attraction to Marian. The latter is deftly handled, considering the story is told from a close third-person perspective focused on Marian.

Gisborne proves to be an intelligent enemy. Although his privilege leaves him with blind spots—as it does with Marian—he’s also not stupid and occasionally turns Marian’s tricks back on her. This makes him a convincing threat. Combining this with his fighting prowess and the weight of the law behind him, Marian risks real peril should he capture her. Nor is he the kind to give up: the more “Robin” eludes him, the more obsessed Gisborne becomes with unmasking the hero.

There are definitely some resonances with modern superhero stories, though they aren’t hit hard. On a superficial level, Marian uses a cloak and mask to disguise her appearance and there are the logistical challenges of having her costume and weapons where and when she needs them. But, more importantly, Marian wrestles with her dual identities. She must keep her identity a secret if she wishes to protect herself and her loved ones.

That identity is also a precarious source of power. As she interacts with the Merry Men both as Robin and as herself, she sees clearly how their attitudes change according to the identity she’s presenting to them. It is galling to her that they would rather believe she was the ghost of Robin or even some other strange man posing as Robin than open themselves to the idea she was a woman, let alone a capable one. As Marian, they treat her respectfully, but carefully—like a precious object to be protected. The idea of her also being a warrior is inconceivable to them. And so Marian fights to preserve her anonymity in order to keep her authority over them as much as anything else. However, shouldering the burden of her secret alone is a tall order and although she panics as people start figuring out who she is, she’s also relieved.

Key Merry Men make their appearance. Will Scarlett and Alan-a-Dale play significant roles, with Little John more in the background. Friar Tuck also makes an appearance, although not in his usual form.

The pacing worked well, with a nice balance of action sequences and more intimate moments between Marian and the people in her life. Although it’s nominally a historical novel, it doesn’t get bogged down in detail designed to show off the author’s research. I should also note I’m not much of a historian, so I couldn’t comment on the accuracy of the details that are present—although I will note that potatoes are mentioned at one feast, which is a few centuries too early for their arrival in Britain.

On the whole, I found Sherwood gave me everything I wanted from a feminist retelling of Robin Hood and I enjoyed it immensely.

3 Responses

Oh this sounds fun! I’ve heard about this author for a while, but haven’t read anything by her yet. This sounds like the perfect place to start!