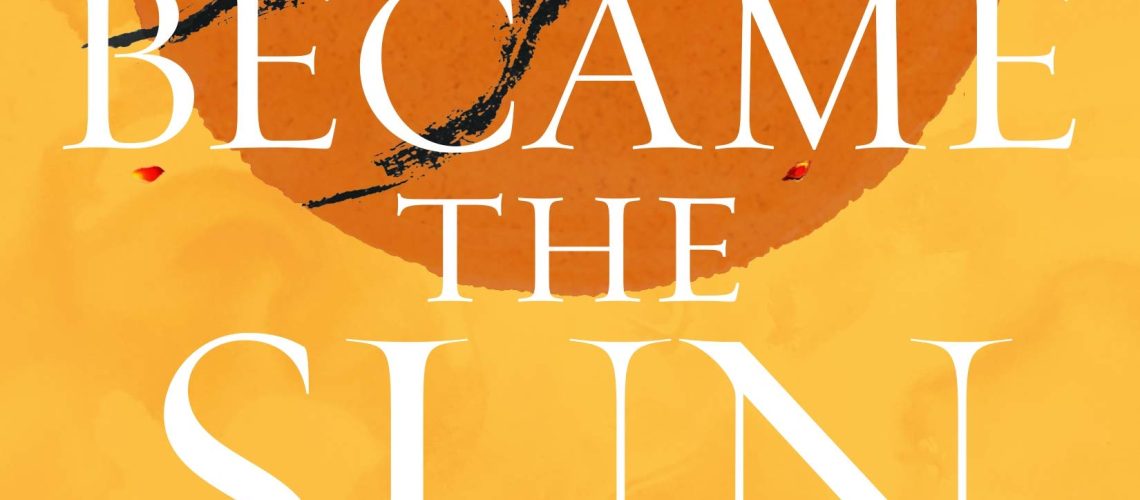

In Shelley Parker-Chan’s She Who Became the Sun, a mostly historical fictional take on the end of the Yuan Dynasty becomes out-and-out fantasy when the author genderflips the future Ming Emperor, and adds some mild supernatural elements in the bargain.

Western education, when it comes to the history of China, can be rather scanty in my experience. If you are lucky, you get a list of Chinese dynasties with little context as to what they are and how they came to be. The Opium Wars and the weakness of 19th-century China is touched on, for reasons that should be obvious. Further back in Chinese history, you get a mention that the Mongols conquered China at one point, although how that rule came to end is, at best, described like a lot of dynastic changes, in vague terms of “rebellion”. If you dig into Chinese history, there is richness, drama, intrigue and amazing stories at the hinge points of the various dynasties.

In She Who Became the Sun, Shelley Parker-Chan decides to make a fantastic version of a story that is already fantastic. In our real history, a former monk, Zhu Chongba, is the unlikely climber of status and intrigue, coming to dominate a faction of rebels against the Mongol Yuan and eventually overthrow it. In real history, Zhu was an orphan who joined a monastery to avoid starvation (China at this time was going through a severe period of drought and famine), and eventually joined and rose in the ranks of the rebels, going from poor peasant, to rebel leader, to become the Howgwu Emperor.

What Parker-Chan does in She Who Became the Sun is to tell the story of a young girl . At the start of the novel, drought and famine has reduced her large family to three: Herself, her father, and her 11-year-old eighth-born (and thus lucky) brother: Zhu Chongba. A portion of the dwindling food that the poor family has is used to pay a fortune teller to tell Zhu’s fortune, and to confirm that he has a great destiny indeed. But when the lazy, spoiled Zhu and their father are killed by bandits looking for food, the remaining girl sees that she has one chance at survival. To travel to the nearby Monastery, which her father had promised his son to years ago, and to pose as Zhu Chongba. To not only lie and survive as her brother, but, perhaps, if she can, to take his destiny for greatness. From the walls of the monastery, to the rebel camp, Zhu greatly dares in order to try and achieve her destiny. It’s a fascinating character arc and set of set pieces of characters, relationship maps, and ultimately challenges. Throughout, Zhu is a human and relatable character that the author invests heavily in, and gives the reader room to sympathize and align with. So the parallel to the real life story of how a poor peasant turned mendicant monk turned rebel reader comes across here as fantastic (in the sense of fantasy) but not unrealistic.

The primary fantasy element of the novel is that Zhu has an ability to see ghosts, a trait that she does not apparently share with others, and is not an expected ability in society. It quite disturbs Zhu, but it is a trait and a feature of the world that the author uses a very light hand, to effect, lighter than I thought it would be, to be honest. It is mainly used for character development for Zhu more than anything else, to help tell her story.

Zhu’s story is the primary story of the novel, and for a lot of writers and a lot of books, this point of view would be more than enough for a novel. It’s a rich and twisting story,as Zhu tries desperately to survive, to avoid detection as a girl, and, once she has some legs under her, to try and grasp that destiny that was promised to her brother. The touchstone of relatively recent reads is the first of RF Kuang’s novels, The Poppy War. The striving and pressure-cooker environments that Rin faces does parallel what Zhu goes through, starting with a very impoverished, hardscrabble beginning and going on, including and up to getting caught up in the deadly coils of war. Readers who enjoyed The Poppy War and Rin’s story will, I feel, glom onto Zhu’s story, as I did, and I did.

But the novel is more than just Zhu’s story. The novel also brings us into the point of view of the decaying Yuan Dynasty Mongols. Here, the survival-turned-intrigue story of Zhu is swapped for a cast of characters equally as passionately written, described and interacting with each other, and the rebels, as Zhu. There is a Tv Tropes entry for “Deadly Decadent Court” where you have a ruling stratum who strive, scheme and intrigue against each other all the while trying to gain power and status for themselves, and only secondarily sometimes, work for the polity they are supposed to support. The late Yuan dynasty court as seen here by Parker-Chan has all of this in spades. Once we get Zhu’s story truly started, we start switching back and forth between Zhu and events with the Mongol camp. General Ouyang and Esen have a deep relationship, one that transcends the fact that the former is a eunuch and the other is a Mongol Prince, and relations between them are not only forbidden, but Ouyang himself has crossed loyalties within his heart, for what the Mongols did to him, and also to his family.

It should be noted that Zhu’s ruthlessness is definitely something that pushes the book into a content warning situation. Some readers may not want to engage with the book based on this strand.

I really liked how the author used the idea of the Mandate of Heaven in a visible and palpable way. As mentioned above, there are not a lot of traditionally supernatural elements that many might expect in fantasy1. The ghosts that the protagonist sees, that run to and inform her as a character, certainly are the major supernatural element that we find in the novel. That in itself would be enough to qualify this as fantasy, especially because of the lovely tension we have regarding that rather rare ability. But the Mandate of Heaven, a phrase that, if you know anything about China, you have likely heard a version of, has a supernatural manifestation, here, too. In Parker-Chan’s novel, those who have a claim or a potential hold on power and the authority to rule can visibly manifest it as a light. The stronger the light, the firmer and more secure the Mandate of Heaven is in that individual. So we get word that the Emperor’s light is weak and has not been seen in public for quite some time, and that other individuals among those who might supplant the Emperor, and the Dynasty, have mandates of their own. This idea makes me think of the show “Kings”, where David’s potential as being the chosen of God to succeed Silas was visibly shown as a crown of butterflies flocking around his head. There are intimations at the end of the novel that this light of the Divine Mandate ability may have other consequences, as well.

The style of how Parker-Chan writes all of this is vivid, immersive and striking. She uses a variety of imagery and metaphors that describe individuals, gestures, actions and maneuvers that bring the writing to life. Everywhere, the text is rich in detail. Be it describing the appearance of a character, how a shadow looms over a character like a mountain, or how cabbages scented a room, the language extends to the character themselves, who see the world in this vivid imagery, as when a brother is reminded of the mating of swallows in watching his sibling eat with chopsticks.

I highly enjoyed She Who Became the Sun, and I think it sits proudly in the burgeoning tradition of major epic fantasy fiction which is set outside the figurative Great Wall of Europe. It provides, too, a window into fantastic and historical traditions that are only now getting wide exposure outside of China, enriching and expanding the potential playground of the imagination, and the people and voices who tell those stories in that playground.

Zhu’s story is far from complete by the end of the novel (given the historical parallel/model/retelling, there is a LOT more to go) and I for one am eager to see where Parker-Chan takes the story, both with and away from the historical model. In other words, more please!

1 That is a whole other can of worms. Does fantasy need explicit supernatural elements in order to be fantasy? Can fantasy be fantasy without “magic”? Nowadays, I say, of course, but there are still people today who argue otherwise…and when I was young and callow, I wondered if something like Swordspoint, whose only fantastic element is that it takes place in another world, was “really fantasy”. It took me a little bit, then, to conclude it was fantasy. In the case of She Who Became The Sun, there are enough fantastic elements that I think it is unquestionably genre, although I think a more interesting question is, is this novel a fantasy novel, or an Alternate History novel? Or is it both?