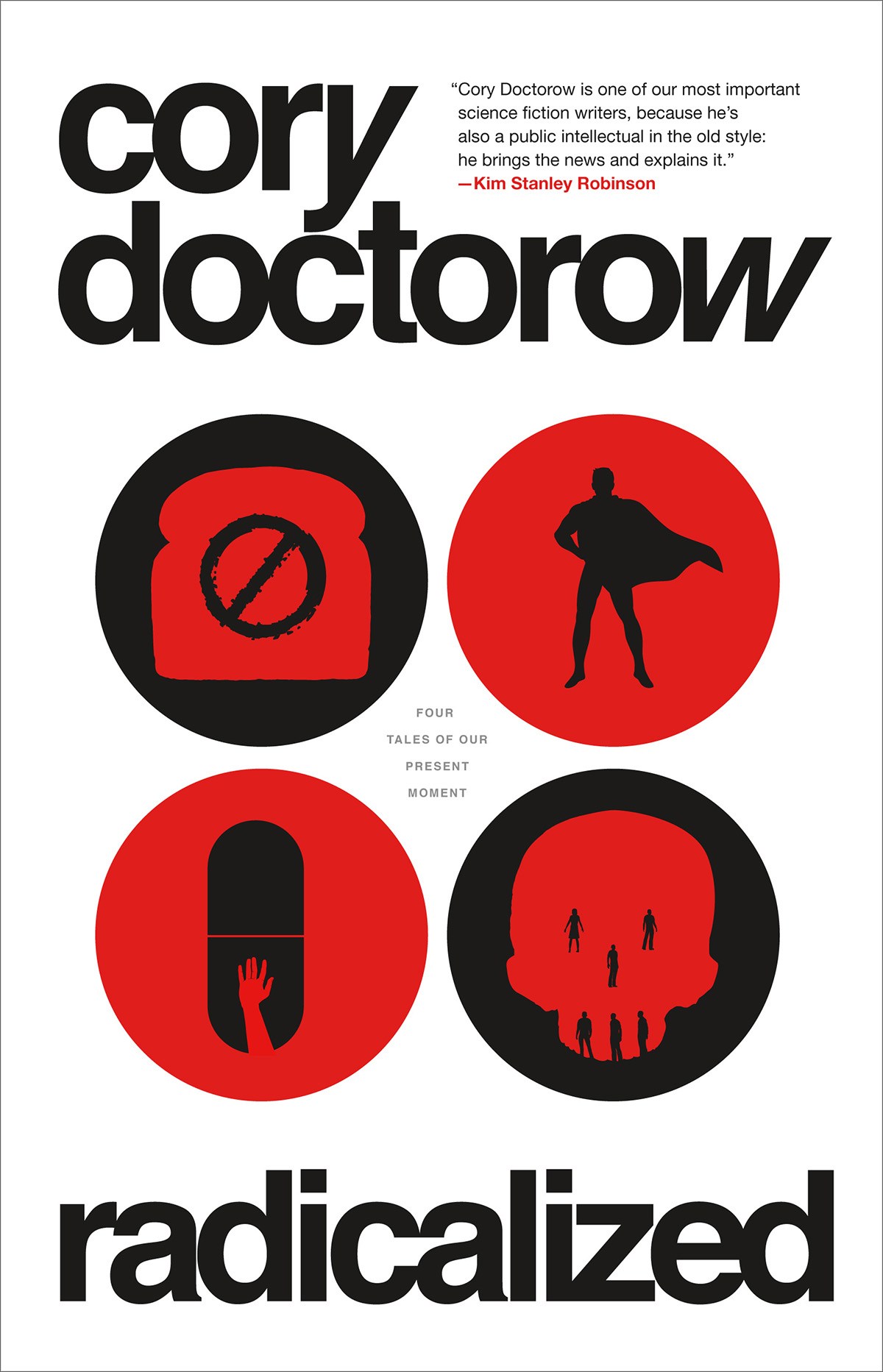

Radicalized, the new collection of four novellas by Cory Doctorow, features an uncommon structure for a book. Authors tend to release either standalone novels or collections of short stories. Sure, sometimes they’ll release a standalone novella or include a novella or two in a collection, but I’m not sure I’ve ever read another book composed solely of a handful of novellas before. However, I really enjoyed this structure, and I wish more authors would release books like this.

Although the novellas are unconnected and each stand on their own, their interweaving themes of technology, activism, politics, and society work together to make Radicalized a cohesive and powerful collection. And it’s timely too. In a recent interview, Doctorow said that he “didn’t intend to write ANY of these — they got blurted out while I was working on another book.” The stories deal with refugees, police brutality, terrorism, preppers, and other elements of our increasingly dystopian modern world. Since there’s so much to talk about here, I’m going to explore each story individually.

Unauthorized Bread

Unauthorized Bread

Have you ever had a printer that only accepts ink cartridges produced by the printer’s manufacturer? What about a toaster that only accepts bread authorized by the toaster’s manufacturer? That’s been Salima’s problem — only things just got worse. The company that makes her toaster just went defunct, and now her toaster refuses to toast anything.

Why doesn’t Salima just throw it out and buy a new toaster? Perhaps one that isn’t so discriminatory? Salima is a refugee/immigrant who lives in low-income housing, and her toaster, her dishwasher (which only accepts authorized plates), and her washing machine (which requires Salima to buy compatible detergents) all come with the apartment. She’s not allowed to throw them out, and she can barely afford to replace them. After Salima’s dishwasher and toaster both stop working, Salima jailbreaks all the appliances in her apartment. It’s a sweet taste of freedom, and Salima shares it with her neighbor’s son, Abdirahim, who in turn shares it with the other low-income residents of their building. The residents finally have control over their own homes, finally have the ability to buy “unauthorized” brands and save some money, and … they discover that because of this, they’re at risk for being evicted and/or prosecuted.

“Unauthorized Bread” is classic Doctorow, a fun activist story about hackers that’s grounded in how computers actually work. If you’re familiar with Doctorow’s work, “Unauthorized Bread” may feel like a splendid mashup of Little Brother and For the Win. It’s about technology and power, about how empowering learning about and hacking computers can be, but also about how powerful people attempt to use technology to exert control over others. The story also explores the promises and challenges of solidarity. Salima meets Wyoming, a young, white programmer who works for the company that manufactures her toaster. Wyoming may be a useful ally to Salima, though their relationship is fraught with danger for both of them. I loved how Doctorow used Wyoming to explore how allyship is not only important, but also complicated and difficult.

This story is didactic. Doctorow clearly wants to convince his audience that digital locks (DRM or Digital “Rights” Management) are anathema, which isn’t surprising considering that Doctorow has been working with the Electronic Frontier Foundation to repeal laws protecting DRM. If you’re a reader who categorically dislikes didactic work, this novella probably isn’t for you. Personally, however, I do enjoy didactic work so long as it’s well-done, important, or interesting, and I quite enjoyed this story. “Unauthorized Bread” is didactic in a fun way. It educates and raises consciousness without overly feeling like an essay or a lecture.

Nonetheless, I do have one complaint. The other three stories read to me as well-executed novellas. This story, however, felt a little awkward at the novella length. The ending felt a little rushed, a little cut off, as if we only got Act 1 of a novel. It’s a good act, and it doesn’t end on a cliffhanger, but I wasn’t completely satisfied with the ending. If Doctorow ever returns to this story and turns it into a novel, I will definitely want to read it.

Model Minority

“Model Minority” is a superhero story that deconstructs and interrogates the prototypical superhero story. The American Eagle, an all-American superhero reminiscent of Superman, has been silent and complicit for too long. He has spent too many years in service to the American government while the state oppressed people of color. Now Eagle is finally ready to take a stand. Unfortunately, even if you’re loaded with superpowers, you can’t just punch systemic racism in the face. So Eagle starts small, trying to help one victim of police brutality find justice. But even in this small act, Eagle finds that he is relatively powerless. His intervention actually ends up making things worse for the victim. Meanwhile, activists critique him for failing to address systemic issues. And soon, the country turns on Eagle, questioning his whiteness and patriotism. Can he really be white if he’s an alien? Or, more to the point, if he resists racist police brutality? Is he really an American?

The story also features Bruce, a defense-contractor playboy who moonlights as a superhero. Bruce only fights crime, not racism — that would be too controversial. He is a fantastic foil to Eagle. Smart and cynical, Bruce tries working from within the system to change it. He’s hesitant to challenge racism too overtly because he knows that in America, that’s how you lose power. Bruce makes Eagle look foolish while Eagle makes Bruce look complicit and self-centered.

“Model Minority” explores how powerless and ill-equipped superheroes are for dealing with systemic injustices. Ultimately, the real heroes of this story are the people, not the American Eagle or any of the other superheroes. It makes me recall Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States, the central thesis of which is that real change comes not from extraordinary individuals, but rather when the people, working together, force it. Eagle can’t solve the problem here — that’s the whole point of the story. Given that, I was afraid this story might end on a hopeless note. However, the activists in the story are able to resist and challenge American racism in ways that Eagle is not. This story is not optimistic, but the presence of the activists does make it a hopeful one.

“Model Minority” is a somewhat challenging read (given the racism and police brutality), but it’s also a delightfully contemporary story, mashing up our current superhero craze with progressive politics. I imagine this might be most readers’ favorite story in the collection, although the next one is probably the most powerful story of the bunch.

Radicalized

“Radicalized” may have been one of the hardest things to read that I’ve ever read. It’s about cancer, healthcare, radicalization, and terrorism. Joe Gorman’s wife, Lacey, is diagnosed with stage-four breast cancer and given three months to live. Miraculously, it goes into spontaneous remission and she recovers, but not before Joe starts frequenting “a forum for very angry people whose loved ones were dying or dead.” The forum’s name? Fuck Cancer Right In Its Fucking Face (FCRIIFF). It’s a forum where some members routinely contemplate suicide. Meanwhile, other members daydream and joke about (while yet others actively encourage and endorse) blowing up health insurance headquarters and executives.

Despite what Trump’s rhetoric may have you believe, the greatest terrorism threat you face probably isn’t from the Islamic State, al-Qaeda, or similar extremists. Rather, it’s from white men, especially white nationalists and far-right violent extremists. This story dives into and explores terrorist threats from white men, but it doesn’t focus on school shootings or violence toward Muslims, Jews, or people of color. Rather, “Radicalized” is speculative fiction, asking instead how the messed-up state of American healthcare might radicalize white men into committing acts of terrorism toward insurance companies and executives. After reading this story, I’m a little terrified to admit that I’m surprised such acts of terrorism haven’t happened already. This story is one of the most serious, intelligent, and original explorations of radicalization and terrorism that I have come across in fiction, engaging with questions of technology, politics, and race. For example, one question the novella raises is: if white men start blowing up insurance companies and killing other white men, how long would it take before the public calls them terrorists?

I’m tempted to use the term “domestic terrorism” to refer to this story. It seems like it would fit. The US has a legal system which discriminates between domestic and international terrorism. Domestic terrorism, the idea goes, involves citizens committing acts of terrorist violence within their own country for primarily domestic concerns. That’s what happens in this story. But these days, in the wake of the Christchurch tragedy especially, we are seeing those distinctions become less meaningful. So while I’m tempted to describe “Radicalized” as a story about domestic terrorism, I’m not sure that term quite fits anymore. Regardless, this topic (indeed, the novella itself) is bleedingly contemporary. Personally, I’ve gone numb to most of these tragic mass shootings, but this story made me pause, reflect, and process.

Part of what makes this story work so well is the protagonist, Joe. He stays on FCRIIFF trying to be a “good guy,” encouraging members not to commit acts of violence toward themselves or others, which makes him much more sympathetic than some of the hate-filled members of the forum. Nonetheless, he slowly becomes radicalized himself. The ending of this story was impossible for me to predict. I was rooting for Joe not to do something stupid (or rather to stop doing stupid things), but I wasn’t sure what he would do or which path he would ultimately take.

As much as I like and appreciate this story, it was incredibly challenging to read. It’s about radicalization and terrorism, which is a topic with far too much contemporary relevance. It’s also about terminal illness, the death of loved ones, and the messed-up American healthcare system (and the surrounding politics). So while I highly recommend this story, be warned. This is not an easy read.

Masque of the Red Death

The marketing copy says that this story “harkens back to Doctorow’s Walkaway, taking on issues of survivalism versus community.” This novella could certainly be set in the same universe as Walkaway, but it’s somewhat scant on the details and the specific connections, so perhaps Doctorow didn’t intend it to be set in exactly the same universe. Regardless, “Masque of the Red Death” certainly engages with a similar set of themes: not just survivalism and community, but also cooperation and selfishness amid disasters, catastrophes, and the breakdown of society.

If you haven’t read Walkway (I highly recommend you do, it’s a fabulous book), “Masque of the Red Death” may entice you to do so. Walkaway is what Cory Doctorow has called an optimistic disaster novel. Rather than being a novel about how society devolves into a post-apocalyptic wasteland filled with marauders and bandits, Walkaway explores how in the wake of disaster, people can cooperate, treat each other humanely, and construct a new society. While Walkaway presents a new narrative for the post-apocalyptic life, “Masque of the Red Death” explores the typical narrative about disasters and apocalypses: that humans are greedy, selfish, violent, and power-hungry, and in the wake of disaster, your neighbors are likely to show up at your door with a shotgun. This novella takes that traditional narrative and deconstructs and critiques it. It even makes a little fun of it.

Martin Mars is rich. Rich enough to construct Fort Doom, his very own place in which to safely hunker down through the collapse of society with thirty people whom he has carefully selected to join him. That’s how the story sets itself up: a tale of bunkering it out in the desert through the apocalypse, of relying on your foresight, intelligence, strength, and grit to survive while countless others perish. It’s the narrative we know. But that’s not what happens here. Instead, Martin’s plans slowly go to hell, and society changes rather than completely falling apart. Contrary to Martin’s expectations, society doesn’t become overrun with gangs of marauders.

My favorite scene — which really sums up the heart of this story — involves Martin discovering a town and trying to extort the shopkeeper there by offering protection.

The shopkeeper, Pakistani or Indian and middle-aged, wearing a clean white button-up shirt and slacks, shrugged. “What kind of protection?”

“You know. Gangs, militias, that kind of thing.” He thought about the word he was looking for. “Marauders.”

The shopkeeper smiled. “We don’t have that sort of thing. Thank goodness!” He smiled at Martin. Martin suppressed his disgusted headshake. Give it a month or two, this guy would be dead and everything he owned would be in the possession of someone stronger and a hell of a lot less naïve. Martin almost wanted to shoot the guy himself. Better a good guy like Martin should get all this guy’s trade goods than some marauder.

“Well, if it ever becomes a problem, we might be able to help you,” Martin said. “We’ll check in every week or two, and you let us know if anyone’s bothering you.” That was how you started rebuilding, Martin thought: the strong protecting the weak, the weak giving the strong a tribute and deference.

The shopkeeper gave Martin a funny look and said he would, and then traded Martin a bunch of dried mango for some of Martin’s powdered milk. There were kids in the town and they drank more than the local cows and goats gave.

Martin thinks he’s living an apocalyptic wasteland, and so that’s how he acts: as a gangster, a thug, a wannabe warlord. But he’s operating under the wrong narrative. In this story — like in James Tiptree Jr.’s classic “The Women Men Don’t See” — the real heroes are overlooked and offstage. The true heroes here are the people working to rebuild society, foster community, and repair the sanitation systems. Every time Martin follows his own narrative, he only makes things worse for himself and further imperils those around him.

Ultimately, this story is a tragedy, which shouldn’t come as a surprise given the title, a direct allusion to the short story by Edgar Allan Poe. But even though the story is structurally a tragedy, that doesn’t mean it’s a depressing read. Martin is so unlikable and ignoble that it’s fun — and actually even hopeful — to watch his downfall, to watch his plans and careful preparations fall apart. He is, quite frankly, an asshole, and the story would be even more depressing if everything went according to his plans.

As you can see, there’s so dang much to talk about within each of these four stories. The collection as a whole is remarkably creative, intelligent, and powerful. Please go read it, and then come share your thoughts with me.

Radicalized was published by Tor Books and is available where all good books are sold.