When I say the words “Ursula K Le Guin and her work,” your first thought is probably either Earthsea or The Left Hand of Darkness or The Dispossessed. Or maybe you think of “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas”. LeGuin’s oeuvre, however, is far more than those works. Even within the Hainish verse, there is a host of other in-universe work that Le Guin has written — work that doesn’t get as much attention or play today as The Left Hand of Darkness, the Hainish Cycle’s shining star. The point of this ongoing column is to tell you why works such as this are worth your reading time and attention. Today. In our contemporary moment.

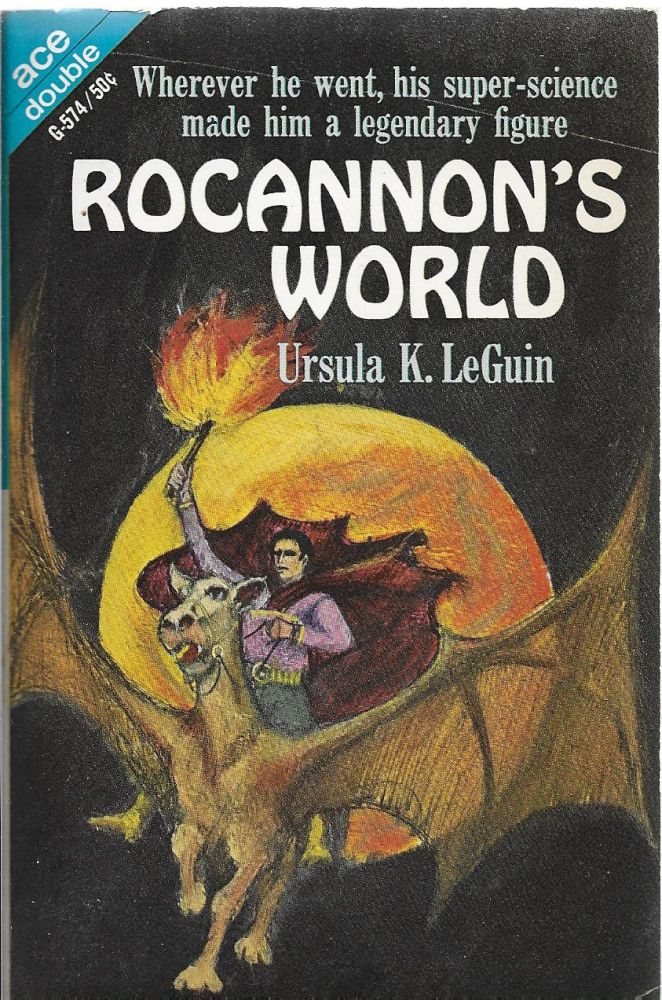

And so, in today’s Mining the Genre Asteroid, I’d like to discuss Le Guin’s first published novel, Rocannon’s World.

Mixing the peanut butter of science fiction and the chocolate of heroic fantasy is a prevalent theme in Le Guin’s early work. She would separate these genres more forcefully in works like The Left Hand of Darkness and the Earthsea series. But early in her career, LeGuin liked to play in that mixed space, and to most wonderful effect. We see that tendency of hers in its purest form in this novel.

Rocannon’s World starts with a contained short story, one of her best short stories not named “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas.” This one is called “Semley’s Necklace.” This story is a prelude to the events of the novel, and describes, using fantasy language and a fantasy viewpoint, the native of a planet seeking to recover a long lost priceless heirloom of her family, the eponymous necklace. It is as if she were in a fantasy story. Her journey across the world and her numerous encounters finally leads her to an underground realm. The inhabitants are what you might think of as dwarves, and their technological wonders come are described overtly in terms of magic. Additionally, the beings she deals with at the end come across as more than human to Semley — almost God-like.

But the careful reader can see that it’s all quite simply a low tech inhabitant meeting higher tech beings, going on a interstellar journey, and seeing the wonders therein. Semley returns from what really is an interstellar journey. The trip, which she didn’t even really recognize was a journey across worlds, takes years. Thus, when she emerges from the Underground Kingdom at last, years have past in the world she knows.

While her journey for herself has been but days, long years have passed in her world. This marriage of science fiction and fantasy is pitch perfect. For all the richness of the story, it’s just a setup for why the main character of the rest of the novel later gets the necklace for himself.

The full novel works on similar principles. Rocannon is an offworld ethnographic researcher from the League of All Worlds who studies the cultures of the nameless planet he is on. In fact, he was one of those who met Semley in the opening story and helped her retrieve her necklace. They might be of lower development — technologically — but they are allies and valued friends. And Rocannon is living rather simply in any event. When Rocannon learns that an interstellar enemy may have set up operations on the far side of the world, there really is no choice but to go on a heroic quest to confront the invaders. For, you see, the invaders have something that Rocannon no longer has: a faster than light communication device called an ansible. If Rocannon can get to it, he can warn League of the enemy’s advance and possibly call down aid in dealing with the the invaders. But with his ship destroyed by those aliens, the journey to get there is long and over land. Thus, the quest narrative kicks into high gear as he and his companions begin their journey.

Le Guin’s anthropological and ethnographical interests, which are more famously visible in the subsequent novels of the Hainish Cycle, are, rest assured, in full flower here. The study of cultures and societies that readers familiar with her later work expect get their start in this book. The League’s perspective on the Prime Directive — giving technological aid to just one of the species/races, the dwarf-like Gdemiar, while taking a hands off policy with the rest — is just one of the anthropological / sociological issues that Le Guin explores in the novel. It’s a Prime Directive a la Star Trek, but of a somewhat more meddlesome sort, picking winners and losers.

Yet, even that element has a heroic fantasy playfulness, since in addition to the Gdemiar, there are other species that look like they are out of a fantasy novel. We get the human-like Liuar, the Elf-like Fila, the dangerous Winged Ones, and the rat men like Kiemhrir. This is a world that feels like it belongs like Dungeons and Dragons, full of competing and interacting sentient species.

The novel works both on the SF anthropological level, reflecting how these species all interact and deal with each other, and also on the heroic fantasy level, adhering the the idea that this really is a fantasy world.

The journey itself likes to confine itself for a large portion to those fantasy motifs, making sure every so often to touch back to its SF roots. For example, the Liuar use giant, cat-like windsteeds for long distance travel. However, Le Guin assures us that the gravity and air density make them plausible from a SF viewpoint.

That duality of SF and Fantasy viewpoints goes into the character of Rocannon as well. He does acculturate to the world he is stuck in, embodying the role others give him as “The Wanderer.” This culminates in a wonderful sequence that pushes the novel to it’s most fantastical bits: Rocannon engages with the planet and bonds with it on a psychic level. He comes away changed by the experience, more ready than ever to protect the planet against the invaders. This is the core sequence — where Rocannon must fully become part of the world in order to protect it. The journey to this moment is a fantasy-style one in which he becomes a traveler and outsider. Here, he sheds that, and becomes fully part of the world. It makes me think of the Gaia Hypothesis or the endgame sequence to Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri.

This really is a capstone sequence. All that Rocannon has experienced wraps up in his experience on the mountain. While the novel does run through his final efforts against the invaders, his planet experience is the true climax — and the true point of the book: To protect something, you sometimes have to become part of that something, body and soul.

Does the novel have any value beyond completists and scholars? Are readers better served with going to The Left Hand of Darkness? I think the novel matters today as a way to better understand how Le Guin explores the themes and elements common in her later works. To better engage with her more famous novels, her original novels provide a window into how and what she explored in her more famous work.

Beyond that, the novel enjoyably shows that you can explore deep questions of ethnography, anthropology, the Gaia hypothesis, and more in an entertaining novel that transcends genre boundaries. The novel shows the possibilities of science fiction even as it keeps you turning pages.

Rocannon’s World is a richly imagined work by an expert in the craft. While I appreciated it as an excellent tale the first time I read it, this re-read helped me see just how honed Le Guin’s craft was in her early career. If you want to mix that peanut butter and chocolate and get the LeGuin experience in a novel less read than her usual favorites, I invite you to take a trip to Rocannon’s World.

Mining the Genre Asteroid is Paul Weimer’s column where he takes a look back at an older genre work, especially those that are lost, forgotten, or by or about marginalized peoples, and brings a fresh and modern perspective to the work.