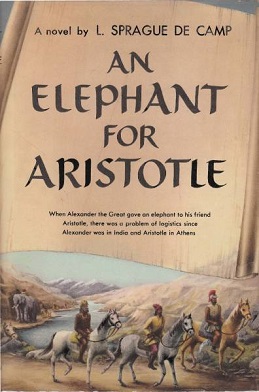

It’s a bold idea for a historical novel, but one with strong reasoning behind it. Thousands of miles from Greece, at around as far as he got away from home, Alexander the Great of Macedon first encountered the (then, to the Greeks) mysterious and legendary creature known as the elephant. Note that Aristotle, who was Alexander’s tutor, although he did not accompany Alexander on his quest, describes elephants as if he saw them in person. Consider that in the following centuries, elephants would be imported to the west by the successors of Alexander in great numbers. Therefore, it is possible that Alexander the Great sent an elephant to his old tutor, the first elephant sent to the west.

The fictionalized story of the transport of an elephant from India to Greece is the subject of L. Sprague De Camp’s novel An Elephant for Aristotle.

Our point of view character is Leon, a fictitious cavalry officer. In the wake of the Battle of the Hydaspes (Alexander’s big classic battle in India), Leon is given a long awaited promotion—but with it a seemingly impossible task. Alexander has decided that an elephant (and a substantial sum of money) should go to Athens, with the elephant going to his old tutor Aristotle. Leon has been tasked with taking a squadron of men the thousands of miles’ journey it would take, back through mountains, deserts, raging rivers, grasping officials, bandits and much more. Keeping an eating machine like an elephant alive, and keeping the silver in his chests safe, will be anything but easy, as Leon quickly learns.

De Camp uses this narrative to do some rather interesting things in what was his first historical novel, as Harry Turtledove noted in his introduction to the edition I read. The Alexandrine Empire (which east of Turkey and west of India would soon become the Seleucid Empire after Alexander’s death) is one of the most epic settings in history. Not until the full breadth of the Roman Empire would you get a single polity with such a wide range of peoples, cultures, terrains and things to see and encounter. From Elephants in the east and the Indus River, through the Hindu Kush mountains and its tribes, to rich Mesopotamian cities full of traders, sorcerers, priestesses, and more, to the wonders of Egypt, and the glory that was Greece, if you want to find it, it was there. You could even have a D&D party wander a landscape like this. These people believed in demons and spirits, believed sorcerers had real power, there were literal lost tombs from earlier civilizations to find, bandits, perilous terrain and much more. Having Leon cross this wide expanse with a small party gives us a whole suite of situations for the reader to encounter.

And not just situations. Leon of Atrax winds up becoming one of those historical fictional characters who meets a wide swath of people of the time and place, starting with Alexander and his generals and all the way to Aristotle himself. De Camp gives us a list at the end of all the real people that Leon meets on his journey, from Macedonian generals to Persian satraps, princesses and princes, bankers, philosophers, petty tyrants, and much more. This means of course that we get De Camp’s point of view on these characters and their times. Alexander only is in the narrative at the beginning, although he looms over it as the sponsor of the expedition, and of course the ruler of Western Asia.

As far as the rest of the characters go, besides Leon himself, De Camp takes a tack that has, I think, some mixed results. He’s up front about it in the beginning of the book, so I knew what to expect, and I’ve read De Camp do it before (In The Incompleat Enchanter, for example, we get a group of trolls who talk and act like Italian-American mobsters). To try and show the wide range of cultures and peoples and how they might have sounded to each other and not to sound the same, even for everyone speaking Greek (and especially to help distinguish the many kinds of Greeks), De Camp gives each of the different peoples and cultures in the book a particular accent and diction and style. Athenians have a Received Pronunciation and diction. Spartans sound like Southerners. Ionians sound like Cockneys. Persians and Indians have accents and speaking patterns of their own, too.

While for various secondary characters this in fact works well, I think it falls down when it comes to our main character, Leon. For Leon and the other Thessalian cavalrymen who are in the narrative, De Camp has chosen to have the rustic, rural Thessalians sound like he is from north of Hadrian’s Wall. And it breaks my immersion a bit at this stage to hear Leon refer to laddies and buckies and in general sound like a transplanted Scotsman. While it makes him and the Thessalians definitely distinctive from the Macadonians, and other Greeks, it might be too strong an effect and done a bit too much for my taste. It does help readers who might think the “Greeks” were all alike and disabuse them of that notion, but I think De Camp could have handled it better by dialing it back a bit. But it must be said that the Thessalians (and the Macedonians ) were rather clan-based, so I can see just why De Camp picked Scotland for the Thessalian accent and attitudes.

This novel is more than just the diverse terrain and the characters met, no matter what their accents might be portrayed as, however. De Camp uses the novel in order to comment on the life and times of Alexander the Great. De Camp has opinions on Alexander’s policies, campaigns and ideas and we get a variety of viewpoints on them as Leon and his troop make their way west toward Greece. In addition to Alexander the Great, we get discourses on philosophy, history, religion and a lot more. Come for the action and adventure, stay for the discourses, debate and slice of life.

And the novel proves that even classic novels could and can be diverse. This diversity falls down a bit when it comes to female characters (although the party acquires a major female NPC halfway through the trip) but otherwise, we get a variety of people of various nationalities, and sexual orientations. Much to my delighted surprise, we even get what today we would call ace representation among Leon’s group, as a philosopher among Leon’s party most definitely identifies himself as such. The character’s lack of attraction to either sex is commented on but that’s about it. This reinforces the clear point of view that De Camp promotes in the book, and that is one of multiculturalism and diversity being good things for people to experience and for polities to have. Time and again, having a wide and diverse group, or tribe, or nation is superior, clearly, to monoculture alternatives. The denouement of the book, which I will not spoil, brings that point home, if somehow you missed it throughout the text.

An Elephant for Aristotle is one of the classic historical novels set in the Age of Alexander, every inch the equal of more famous historical novels by authors such as Mary Renault and Judith Tarr. What it offers genre readers, as a historical fiction novel, is that it shows how the techniques of genre writing, particularly in worldbuilding, can make a historical fiction novel feel like fantasy. And it shows that no matter what or where a book or story is set, you can have a novel with good representation of all sorts of people. And finally, it gives freedom to creativity in coming up with settings, characters and situations. In the introduction, Harry Turtledove says in his introduction “So, in this case, fiction is not stranger than truth. As best I can tell, they walk each other to a dead heat.” This novel is definitely proof of all of that.

3 Responses

I happened to just finish this book the other day. One of the more unique stories I’ve read in a while. Between the descriptions of the various cities the hipparchia made its way through and the different dialects, I found it very immersive.

De Camp obviously has something personal against Aristotle, so I found the passive aggressiveness toward him quite irritating and unnecessary.

All in all though, I really found the book great.

I’m sorry your comment got caught in moderation, Jake! But I’m glad you found the book interesting. — editor Trish

De Camp does like to grind his axes.

Thanks for reading my review 🙂