For my contribution to the theme of this month, I was originally going to put together a short list. But the more I thought about one of the entries on that list, the more I felt I had to devote the entire post to this one book, and even that would fall short of doing it justice. Because if there is one book that has brought me more joy than any other, it would have to be Denis Gifford’s A Pictorial History of Horror Movies.

Gifford’s tome came into my life in March of 1976, and it changed everything. I was already obsessed with monsters and dinosaurs, and I bought the book because it had pictures of the biggest dinosaur I had ever seen: Godzilla. Gifford’s text introduced me to the wonders of the cinema of Georges Méliès and James Whale and Val Lewton, to German Expressionism, to Lon Chaney and Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, and in short defined the academic, creative and professional paths the rest of my life would take.

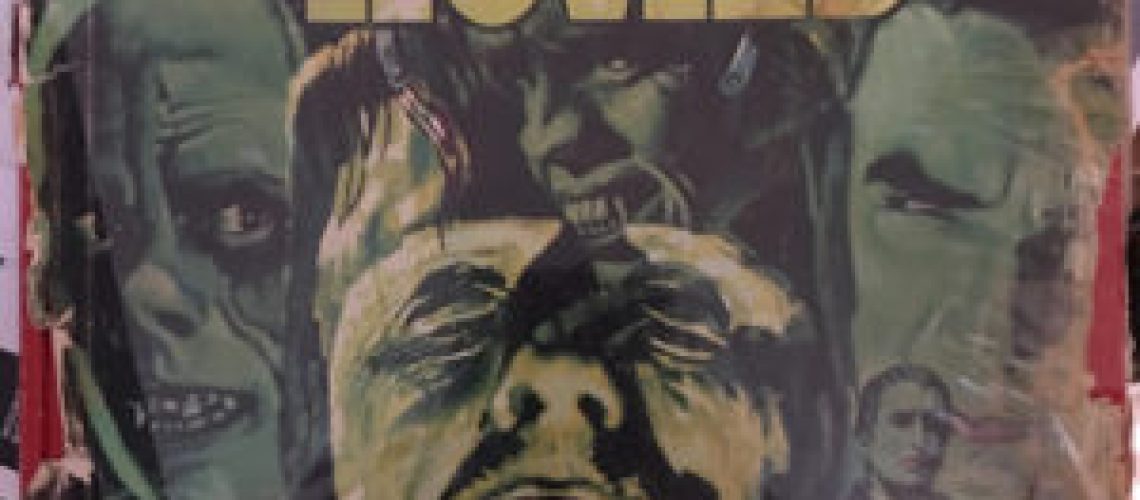

This is my copy, bearing the marks of 40+ years of love, and writing about it makes me want to re-read it yet again. Of course it’s out of date. It was in 1976. Though Gifford just manages to reach the beginning of the 1970s, his coverage of anything after the 1950s is brief and largely dismissive. He has no love for Hammer films, and though he includes stills of Mario Bava’s Kill, Baby, Kill and Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face, there is otherwise virtually no mention of any of continental Europe’s horror films after the end of the German Expressionist period. (It would be Phil Hardy’s Encyclopedia of Horror Films that would properly introduce me to Bava and the European Gothic.) And to read this book, you would never know that Night of the Living Dead ever happened. And speaking of 1968, the only mention Rosemary’s Baby gets is as a passing mention at the end of a paragraph on William Castle.

But love is not love which alters when it alteration finds, and for all that I can now see the imperfections in the book that was the Bible of my childhood, I love it no less than I ever did, and I appreciate it all the more for everything it has given me. It did more than shape me. It was a source of endless entertainment and of comfort. I recall one night in early adolescence when, plagued by a series of nightmares, I was terrified of going back to sleep. I turned the light on, picked up Gifford’s book, and started to read. Before long, the familiar narrative had comforted me. I was among friends, and all was well, and it was okay to go back to sleep.

So yes. Comfort. Joy. Wonder. Purpose. These and more were Gifford’s gift to me, for which I am profoundly grateful. I know I’m not the only one to have been marked by the book. There are plenty of other Monster Kids of a certain age for whom this was a formative reading experience too, and who (I’m willing to bet), also experienced the trauma I did on seeing the still from the 1966 version of the The Black Cat on page 206. So this is my book of joy, and my gateway to the universe of joy that is the horror film. There are used copies still floating around out there, and they’re not too expensive, so I hope new readers might yet discover its pleasures.

I’ll close with a link to Georges Méliès’ The Monster from 1903. The description in Gifford’s book fascinated me for decades, and when I finally saw the film, it did not disappoint. It features some of the most nightmarish imagery from the first decade of the horror film.