One of the reasons I have always preferred Marvel over DC is the fact that it’s world, however absurd at times, at least tries to explore what might happen if a bunch of people with extraordinary powers popped up in our neighborhoods. In short, humans have a tendency to freak out. In a weird, unexpected way, the Marvel Universe (Earth 616, not the other versions, which I’m not currently following) is an exploration of evolutionary change, the likes of which we haven’t seen because the last major change in our species “group,” as far as we know, was before written records. I’m talking about the Neanderthals.[1] We’ll never know exactly how humans reacted to those funny-looking humanoids, though we’re pretty sure there was some violence, some sex, and probably some group hugging in certain parts of the world. And in a similar way, we don’t know exactly how humans would react to the rise of mutants; instead, we make educated guesses based on things we’ve actually seen in our written history: xenophobia, eugenics, slavery, murder, and a lot of other nasty stuff (not that we didn’t do anything nice, of course).

So while reading All New X-Men #13, I was pleasantly surprised to see Kitty Pryde (Shadowcat) actually address “passing” in the context of superpowers. To set up the context, here’s a rough back story of the last two years of Marvel comics:

In 2012, Marvel ran a huge crossover event called Avengers vs. X-Men. Basically, previous cataclysmic events have decimated the mutant population, leaving the X-Men and their allies relatively crippled in a world that is still hostile against their kind. In an act of desperation, Scott Summers (Cyclops) tries to use Hope (Cable’s daughter, and, because time travel is crazy, Scott’s granddaughter) to reignite the mutant gene and bring the mutants back into the world. Hope, it turns out, is the next possible host for the Phoenix Force, the same cosmic entity which killed Jean Grey and nearly wiped out the Earth. Of course, the Avengers aren’t happy about this, and so the two groups start a war, which eventually leads to the splintering of the Phoenix Force into Cyclops, Emma Frost, Magik, Colossus, and Namor. They then use their insurmountable power to remap the Earth as they want it to be. Obviously, this doesn’t go over so well. Some really important folks die, the Phoenix Force is eventually “destroyed” (“sent on its way” is probably a better description), and the Phoenix Five, their powers put on the fritz by the possession, flee (Cyclops starts up his own team and school; Colossus joins the X-Force; etc.).

Jump forward a bit, and a dying Hank McCoy (Beast) decides he has to teach Cyclops a lesson by using a time machine to bring the original X-Men (including an unmutated version of himself) to the present. Understandably, this causes a few…problems. The most obvious one is the fact that these younger versions know what will happen to them, resulting in tension within the group, some very awkward reunions, a lot of violence, and a whole lot of confusion — especially for Jean Grey. And that’s where we are now.

That’s the watered-down version, of course.

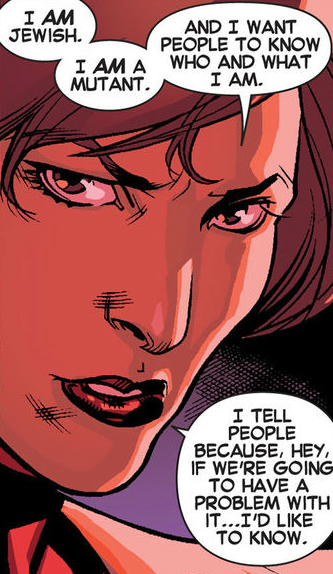

Basically, all of this has led to an honest discussion between Kitty Pryde and most of the original X-Men about the realities of the world in which they are all living, all in response to Havoc’s (Cyclops’ brother) plea to the world for people to stop using the word “mutant” because it offends his sensibilities. Pryde’s response is the following:

Here’s the thing…I’m Jewish. I don’t have a quote unquote Jewish-sounding name. I don’t look or sound Jewish. Whatever that looks or sounds like…So if you didn’t know I was Jewish, you might not know…unless I told you. Same goes for my mutation…I tell people because, hey, if we’re going to have a problem with it…I’d like to know. (Issue #13)

Essentially, Pryde’s statement is a rejection of the concept of “passing,” which is a term typically associated with light-skinned blacks pretending (i.e., passing) to be white. The best way to explain this is to use literature, of which there are two perfect examples.

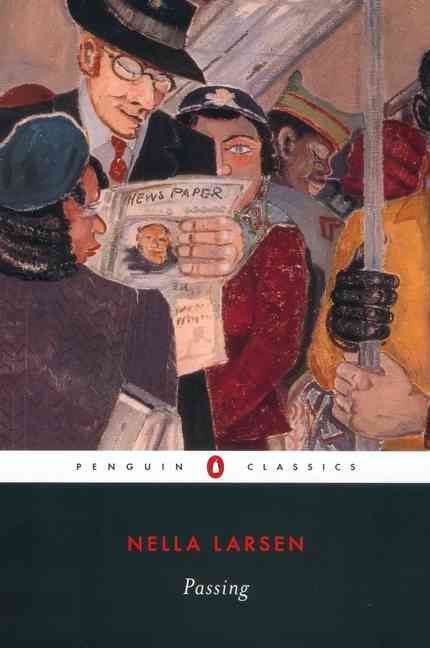

As someone who has tried to teach something from the Harlem Renaissance every time I teach an American Literature survey course, I have become quite familiar with the politically/socially-charged work of black writers from the era. Two of my favorite novels from the period are Nella Larsen’s Passing and George Schuyler’s Black No More. Larsen’s novel follows the conflict between Clare and Irene, two light-skinned black women living extraordinarily different lives: Irene is married to a black man with darker skin than herself and actively engages in the black community; Clare is married to an outspoken racist who doesn’t know he’s married to a black woman.[2] The conflict between these characters boils over when Clare decides to, as Irene puts it, have her cake and eat it too; she tries to participate in black culture, all the while hiding the fact that she is technically “not white” from her husband. The interesting part of the novel is its method for exploring why passing, however beneficial in the short term, is actually quite detrimental on a psychological level. Because Irene only passes to take advantage of certain societal amenities (nice restaurants, etc.), she can still see how trying to consistently pretend to be something you’re not can actually make matters worse. And if you’ve read the novel, you know exactly what that means, which Larsen brilliantly demonstrates in the final pages.

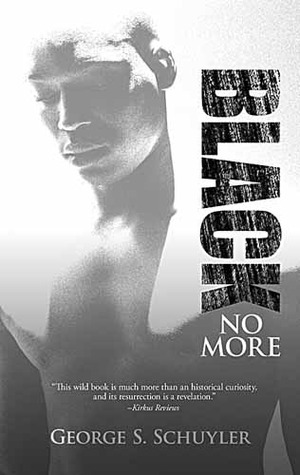

Similarly, Schuyler’s Black No More explores passing and colorism.[3] Set in a “present” in which a black man has discovered the method for turning black people into white people (this based on a real claim in a news article from several years prior to publication), the main character, who was the first man to pay for the procedure, eventually joins a white supremacist group and marries the leader’s daughter. The science fiction concept lends itself well to criticism of white racist culture, black intellectuals, politicians and scientists of all stripes, and so on. In the end, the majority of the white characters are revealed as having black “blood,” which is particularly shocking for the white supremacist leader, who has been preaching against black people for most of the novel. In a sense, the novel is about passing without knowing you’re even doing it, and it uses that perspective to interrogate the culture of racism at its heart.

Whether the writers of All New X-Men knew it or not, they were picking up on these very same concerns in issue #13. Pryde refuses to accept the premise that those who can “pass” as “normal humans” should do so because it is best for them. She supports this refusal by implying that -isms do not dissipate by remaining silent; rather, they must come from open engagement with the public. This is perhaps naive on her part, since mutants in the Marvel Universe are rarely “just the good guys,” but considering all of the crap she has gone through in the last year or so of comics, I can’t say I blame her. At the very least, her somewhat simplistic story about passing (unintentionally, of course) is a reminder that the very concept cannot maintain its integrity in a world where prejudices exist everywhere (there’s also a lot of this “mutant and proud” stuff going on, which comes primarily from the Cyclops camp). In this alternate version of our reality, pretending to be something you’re not is an easy way to make others suspicious; if you saw the movies, you know that one of the ways humans reacted to this was to pass mutant registration laws, which Magneto recognizes all too clearly from the concentration camps.

Still, Pryde’s view is somewhat utopian, to be reductive about it, but the fact that this particular comic actually wants us to think about what you should do if you’re superpower isn’t visible is actually quite interesting. The Marvel Universe has always had a race-argument embedded in its extended metaphor, a fact which the film versions weren’t able to explore in the same depth as the comics have over the last 50+ years. Even if the way All New X-Men has approached the issue reduces the complex social and psychological effects of passing into a handful of pages, it still opens the discussion to the real problem embodied in this world: mutants are everywhere, and either people will go mad trying to figure out who they are (and what to do about said mutants) or they’ll accept it as a course of life and move on. The second choice will never happen, because despite the insane plot points and physics of the Marvel Universe, the writers are still seem determined to address race in a mutant-heavy world. After all, an evolutionary change brings with it several default questions, the most important of which is this:

What makes us human?

——————————————————————-

[1]: Fun fact — some of you have Neanderthal fragments in your DNA. Cool, huh? Except the part where we maybe (might have, sorta kinda) killed them all off. But not before we had lots of sex with them. And maybe shared our secret stashes of caveman pot and Doritos.

[2]: The Harlem Renaissance period is full of stories about people of color (mostly blacks in America) trying to find their place in society. And many of those same stories are painfully aware of the “one drop rule,” which, when applied as a determination for social policy, essentially meant that any hint of “blackness” permanently removed you from “right” society (read: white culture). Schuyler’s novel ends with an amusing twist on this very idea.

[3]: Prejudice against skin color; it is often associated with preferential treatment of whiteness by way of beauty product, such as skin whitening creams in India.