“… And also starring the City of Oshawa as… itself? Sort of?”

There’s a certain kind of joy that Canadians feel on the rare occasions that we get to see Canada playing itself for a wider audience.

Most of the time, Canadian locales in film and TV, for instance, are standing in for places in the US. Toronto, Vancouver, Alberta and miscellaneous picturesque locales serve as, respectively, any big American city for the first two, the wide-open spaces of the west for the third, and the implausibly-Christmas-obsessed small towns called for by the plots of this year’s crop of Hallmark holiday movies for the last. Seriously, this happens all the time. My local pub is in a Christmas movie that was the subject of a Skiffy & Fanty podcast. And that’s not even my favorite example, which is that when I saw the trailer for the first Shazam!, my immediate response was, “Been there, been there, hey I know that variety store!”

There are a whole bunch of reasons for that, including our dollar being significantly below par with the US dollar, and tax credit policies that foster Canada as a location for filming American movies and TV. There are also lots of Canadian TV and movies made by Canadians for Canadians.

But Canada, not surprisingly, rarely shows up as Canada in US media. So stories that are actually about Canada, but are intended for audiences outside of Canada too? That tends to pique interest.

All of which is to say that when I first read this synopsis of The Displaced, a new five-issue limited series from Boom! Studios…

“The city of Oshawa, Ontario and its 170,000 residents have vanished without a trace.

No one remembers it even existed.

As the survivors of the incident start to become forgotten as well, they must seek each other out if they hope to have any chance of surviving in a world where no one believes they ever existed at all.”

Yeah, that got my attention.

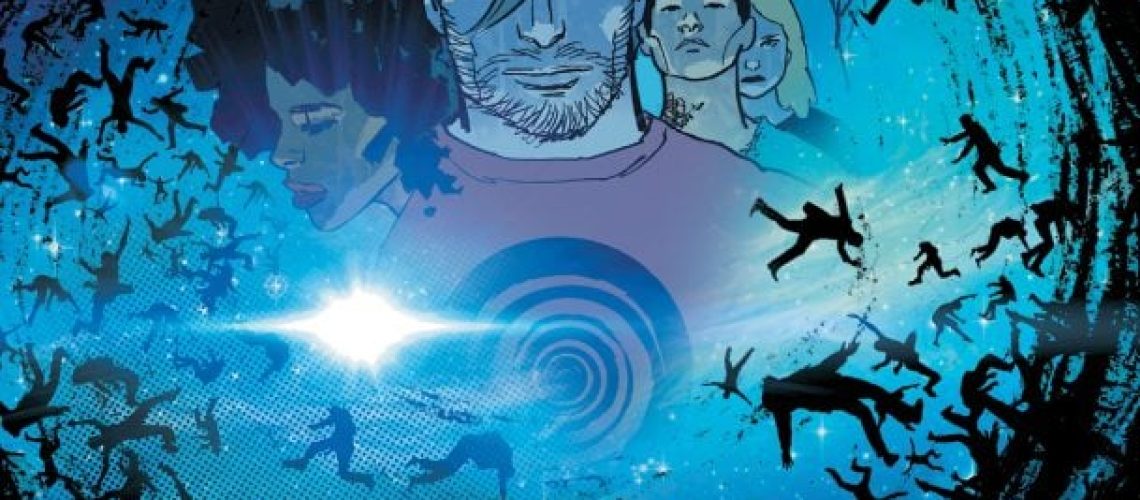

The Displaced

Written By Ed Brisson

Illustrated by Luca Casalanguida

Colored by Dee Cunniffe

Lettered by Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou

Designer Grace Park

Editor Elizabeth Brei

The series is pitched to readers as a “psychological and philosophical mystery” – and both issues to date have succeeded in creating a sense of dislocation, tension, and fear. The idea is unimpeachable: Imagine that your entire hometown disappears, taking with it your job, the place you live, your family – and then you realize that nobody else remembers that any of it was ever there. Everything you care the most about has been retroactively erased from the universe – including you.

Brisson’s writing and Casalanguida’s art work in tandem to effectively establish the terror and the confusion of Oshawa’s handful of survivors and their increasing isolation as they swiftly fall down the entire world’s memory hole. Along with dire warnings that if they don’t stick together and reinforce their memories of Oshawa and one another, they too will inevitably disappear, our key characters one by one realize that their phones don’t work, their bank accounts and credit cards no longer exist, and friends and loved ones from outside of Oshawa no longer know them. Functionally, in our modern world, they already no longer exist.

The Cassandra of the piece is Harold, a mysterious old man who seems to have known that the disappearance of Oshawa was coming and utters dire but unfortunately gnomic warnings – and mentions other vanished cities, that neither the characters nor the readers have ever heard of because they too now never existed. It’s perhaps an obvious device, but a useful one, deployed well. This could happen to you, and no one would ever know, because in the new world, you never were.

What a great evocation of existential dread! Not a Lovecraftian monster in sight, but the cosmic horror has been quite effectively turned up to 11.

So the concept and the hook work. Really well. It got me to buy the first and second issues, and I don’t usually buy periodical comics anymore. So, is there anything that doesn’t work?

There are a few problems, yes. One is structural and not the fault of the creators, but is real. The others… hmm.

Let’s cover the problem that’s not really within the creative team’s power first: Periodical comics, increasingly, just don’t make sense financially for the consumer and particularly in this genre, don’t make for a satisfying unit of story.

An issue of The Displaced is an industry-standard twenty pages; that’s the actual story content, not the front and back cover, the credits, or some additional pages of backmatter devoted to promoting other comics from the publisher. I can read twenty pages of comics in a few minutes, and – for understandable reasons that have to do with the economics of publishing – a single issue cost me over $7.00 Canadian (including sales tax).

That simply isn’t a worthwhile trade-off, in terms of dollars paid to minutes of entertainment received in exchange. This isn’t just me being a cheap curmudgeon – it’s been a growing problem in comics publishing for years, and it keeps getting worse for everyone. The more comics cost, the fewer of them people can buy, which is bad for big and small publishers alike, and is a particular challenge for new series trying to find an audience.

Moreover, a story like this – a psychological and philosophical mystery – is not well served by the periodical format. I read issues #1 and 2 at the same time, and even then the inevitable cliffhanger at the end, following by putting the comic down and picking up another one, interrupted the narrative drive and defused much of the mood and tension that the creators worked so hard and so well to establish. The next issue is almost two months away, after which point I probably won’t remember any of the characters’ names, much less the feeling of dread their situation evoked. Serialization can work to build, rather than alleviate tension – but not in such small doses of story, with such lengthy gaps in between.

This story, in this genre, would have been better as a single graphic novel from the start, rather than being serialized in a way that doesn’t serve the readers or the work itself. That’s not an option that’s available to everyone in comics – there are major publishers of original graphic novels of course, but there isn’t much overlap between them and the creators, genres, and publishers that work within the periodical comics ecosystem that we call the Direct Market. This is an unfortunate example of a series that could only find a home on the serialized-first, periodical comics side of the medium, a home where it isn’t really a great fit.

Of my other two concerns, one might be a me problem.

The probably-not-a-me problem is that I have no idea who most of the characters are. The art by Luca Casalanguida is good at establishing a mood but less good at establishing distinctive characters; it falls within a certain style of comics art that’s visually accessible, with clear strong lines, but a little loose, to let you know that weird shit is probably going to happen – and detailed in backgrounds and settings while being more stylized and cartoony in facial features. In this, it reminds me a bit of Cliff Chiang’s art for Paper Girls.

So I know Harold because he’s an old guy with kooky-prophet hair, and because he has a big role in the story and appears enough to fix him in my memory; Gabby, one of our main protagonists, similarly pops because we see a lot of her with her husband and baby before they disappear with Oshawa, but also because she’s the only prominent Black woman in the cast, and because she has a distinctive trait in smoking. There’s also a cop named Church who isn’t one of the survivors of Oshawa but takes up a whole lot of narrative real estate and has a sinister presence that implies that he knows more than he’s letting on.

Other than that… there’s a guy who tries to take a TV station hostage to remind everyone that Oshawa existed but in doing so separates himself from the other survivors and falls into Church’s hands, and I don’t think we ever learn his name? He’s scraggly-looking? There’s another guy who realizes that the fact that people forget the Oshawa survivors can be turned to his advantage in awful ways. There’s a young woman whose name gets used enough in the same issue that I know she’s Paige.

But there are maybe ten or fifteen other former residents of Oshawa who’ve come together, and I couldn’t tell you one from another. I only know Emmett, who along with Gabby seems to be the co-protagonist, because he has a distinctive t-shirt on. Other than that… he’s scraggly too?

The Displaced opens before Oshawa vanishes, with a conversation in a pub between Emmett and an old friend (who later forgets him, of course) that’s about people they remember from high school, and about what they know or think they know about them. It’s clear that Brisson is setting up a point, here, because of course the entire story goes on to concretize the metaphor: All we are is what others remember. And it’s possible that not giving us the names of seemingly-important characters, of the characters being visually indistinct and sometimes hard to tell apart, so that they slip out of readers’ memories, was a deliberate choice to emphasize that.

But if so, it was a choice that I think doesn’t work – it makes the narrative harder to follow, and the characters more difficult for us to be invested in. I care far more about bereaved mom Gabby, who’s established clear in my mind, than Guy Who Takes Hostages, Guy Who Does Crimes, or Probably The Protagonist.

Finally, the problem that might just be me. That is, the one that very well could be down to a difference between what I was hoping for from the story based on my own understanding of the premise, and what the creators are doing.

For this aspect, I should probably emphasize that Oshawa is a real place, not an imagined or composite one; it’s an actual city, which is more or less the easternmost part of the sprawling Greater Toronto Area. I haven’t spent time in Oshawa, but I’ve been through it, and I’ve been to some of the towns and cities adjacent to it. I could hop on a commuter train and go there today.

But if you asked me to picture Oshawa, I couldn’t picture anything distinct. That’s not a criticism of Oshawa, or me being a snobby Torontonian (although I am) – it’s that so much of suburban southern Ontario isn’t visually distinct. If I picked up a street from London, Ontario where I grew up, and dropped it into Mississauga, Ontario, the suburban sprawl on Toronto’s western border, and picked up another street from there and dropped it in Oshawa?

It would have the same strip malls with the same chain restaurants next to the same gas stations serving the same cars driving back to virtually identical subdivisions.

In short, I thought that by creating a story that was about the city of Oshawa disappearing and being forgotten, that Brisson was going to be exploring, among other themes, the sameness of contemporary life, the way our sense of place has been worn down by capitalism, the way everywhere looks like everywhere else – so that places might as well not exist at all.

That’s not something that the story seems to be focused on engaging with. But while I’m disappointed that this isn’t one of the themes being explored, I also recognize that me hoping for something from the premise that isn’t there isn’t really the fault of the creators. Still, I was hoping for a bit more philosophy from this purported philosophical mystery.

So, based on the two issues I’ve read so far, I’m ambivalent about The Displaced as a serialized five-issue periodical comic book series. A killer hook can only go so far to balance a format that doesn’t serve the story narratively, or me financially.

But I’m looking forward to reading the version of The Displaced that doesn’t exist yet – a complete, collected volume that I can read from beginning to end without two-month pauses in between ten minutes of reading. I have a feeling that more of the weaknesses I’ve called out here are a function of format than just my dissatisfaction with the price point. The characters will almost certainly be more memorable, the forward momentum of the story stronger, the theme and mood more consistently maintained, without lengthy narrative gaps imposed by serialization, mandated by the economic realities of creators and publishers navigating a challenging and sometimes hostile marketplace.

I’m excited to read that story, and I’ll share my thoughts on it when I have.