Not too long ago, I was talking with the rest of the Skiffy & Fanty crew about how it can be challenging for me to find works to review that align with my interests and my goals for this column in a timely way.

Trish, who is smart about these things, pointed out to me that I don’t actually need to always be reviewing new comics and graphic novels, as long as they’re new to me. And of course, that’s entirely correct. In fact, taking the time to look at and discuss something that’s not a new release can be very helpful to works that have fallen out of the hype cycle.

So, it occurred to me, while I was considering this month’s review, that there was an entire fantasy graphic novel that’s been sitting unread on my bedside table since last May’s Toronto Comics Arts Festival. A closer look confirmed that it was published in 2020, which was a year that I suspect we can all recall was a bad time to be promoting new work.

Let us, then, prove that the hype cycle isn’t the boss of us. Let’s have a look at a work of fantasy that takes a deeper look at a video-game-ish life of endless dungeon-crawling and grinding to level up, and wonders what someone trapped in that kind of world would make of it all, the YA graphic novel Penultimate Quest.

“In a witty, genre-defying tale of magic, mystery, and philosophy, brave warriors must learn the difference between diversion and escape as they try to break the cycle of a penultimate quest in which the final fantasy never arrives.”

Penultimate Quest

Story & Art – Lars Brown

Colors – Bex Glendining

“Alma’s Quest” Drawn By – John Kantz

Published by Iron Circus Comics

Publisher – C. Spike Trotman

Editor – Andrea Purcell

Art Director & Cover Designer – Matt Sheridan

Proofreader – Abby Lehrke

Print Technician & Book Design – Beth Scorzato

Harald and his friends Jimmy and Alma are bold adventurers; every day they wake up on the island, grab their gear and supplies, and head into the seemingly-endless dungeon below, always hoping that today will be the day that they face the final boss and the final battle that will mean they’ve finally reached the end of their quest.

Oh, and they don’t really remember their lives before the island. Or how they got there, or when. Or, when it comes right down to it, why they’re exploring this unending dungeon.

Death is a common and painful but temporary inconvenience – if they or the dozens, maybe hundreds of other adventurers inhabiting the island are killed, they re-appear the next day. The only scars they bear are the emotional ones.

The endless grind, and the desperate carousing in the tavern that follows it, keeps most of them too occupied for questions, but Harald begins to wonder about the why and how of this absorbing but nonsensical set-up… and who he is.

What follows is increasing tension between the adventurers as Harald seeks to break the world and set them all free. But the broken world keeps re-setting, replacing the obsession with unending dungeon-crawling with others, equally diverting but equally banal at their heart. Jimmy doesn’t even want to be free, putting him at odds with Harald. And Alma, who remembers far more about her life before the dungeon than she lets on, has her own reasons for trying to reach the final boss.

Let’s start with the element that surprised me the most: Penultimate Quest is absolutely not a comedy. Going in clean, with no more information than what’s on the front and back covers, I was expecting much more of a genre parody than actually appears. I could make a case for the book as satirical, but it’s not the ha-ha kind of satirical; while there’s genre deconstruction taking place, its expression is far more tragic than comic. This is not a “Mornin’ Ralph” “Mornin’ Sam” send-up of adventuring as a grind.

This is, instead, a story about the futility of substituting ultimately meaningless activity for personal growth. The story flashes forward and backwards – to Harald’s arrival on the island and his first meeting with his new friends and faltering early exploration of the dungeon; to the buried and seemingly forgotten traumas of his and the others’ lives before; and in some cases between branches of possibility, where a Harald who never dared to break out of the dungeon has become cold and indifferent after spending a what he’s pretty sure is centuries delving ever deeper with Jimmy and Alma.

And that leads to the great irony that made it difficult for me to fully appreciate Penultimate Quest: It’s clear that Brown’s goal is to demonstrate the futility of empty action, repeated over and over with only variations on a theme. Harald, Alma, and Jimmy are all in their way burying themselves in a series of obsessive but fundamentally meaningless pursuits as a way of not having to deal with the own unresolved traumas.

Depicting how it’s fundamentally unfulfilling to substitute a distracting fantasy for actually dealing with your pains, the hurts you’ve caused others, where your life went wrong and how you might make it right is an admirable theme, but ironically it’s a point that doesn’t take this much repetition to make.

This is a hefty book – almost 350 pages of story – and while I appreciate the intent behind the wheel-spinning cycles of variations, it’s a lot of variation for a theme that I just encapsulated in a paragraph. I can’t help thinking that the point could have been made a bit more succinctly – and with more humor – by using montage and similar visual devices to emphasize the irony that the protagonists, in seeking distraction from the crises of these lives through imagination and novelty, have instead trapped themselves in never-ending cycle of banal sameness. Instead, it sometimes feels like the reader is trapped right there with Harald.

Unfortunately, the tendency of many of the characters to lapse into portentous reflections on what it all means – including Harald, our most frequent viewpoint character – pushed me out when the characters needed to draw me in to engage me through the recurring, deliberately similarly-unfolding episodes.

That being said, there’s a great deal of good spread across the book as well. Penultimate Quest is cleverly plotted. The echoing of events and characters across time frames, settings, and plot threads is painstaking and really well done.

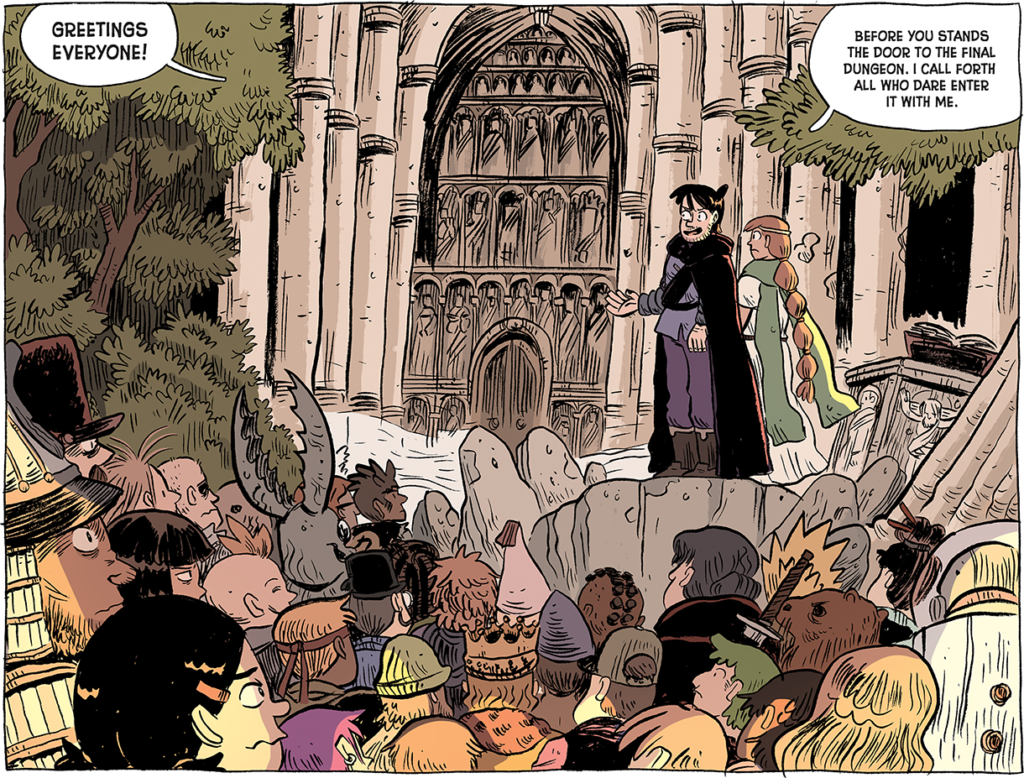

Lars Brown’s art is winning, and Bex Glendining’s colors work well with to help it pop and to make the different environments more clearly distinct – a real plus in a book where so much of the action is set in dimly-lit corridors and grim caves! Given how frequently scenes like that occur, and their literal as well as figurative muddiness, adopting a more deliberately chosen limited color palette – rather than having the limited palette be imposed by the lighting and environment – might have helped make the action more clear.

While John Kantz’s anime-inflected art in the ‘Alma’s Quest’ chapter is fun, I remain puzzled by its presence. I’m not sure what the purpose of having a chapter in a completely different visual style is. That might be an effect of my virtually nonexistent exposure to JRPGs, which I suspect are being deliberately homaged. But the incongruity between the art styles and the lack of context for them, if only on my part, makes the discrepancy feel confusing.

Finally, and this is going to sound like I’m piling on trivial quibbles, but I don’t love the format. As you can see from the images I’ve shared, Penultimate Quest doesn’t have the conventional dimensions of a graphic novel. It’s 9” by 6.75”, wider than it is tall. In another book, this could allow for lots of big widescreen action, but while there are plenty of fight scenes, this is a story that’s fundamentally about the futility of action. I’m not sure what’s gained via a format that’s going to be challenging to shelve with other graphic novels. Perhaps it’s an attempt to emulate the screen of a video game, but if so, it’s a tenuous connection that isn’t emphasized enough in the art to really come across. (It might be just me, but I don’t like books that poke out that much farther on my shelf than the other books they’re with!)

This is a smart book, and an ambitious and interesting one – one that was, in the end, not for me. But that doesn’t me that I can’t acknowledge the strength of the premise and the ideas. If those pique your interest, then with some of those didn’t-work-for-me caveats, you should check it out.