Happy Pride Month, everyone!

Thinking about Pride of course got me thinking about the Lambda Literary Awards, and more specifically its Best LGBTQ+ Comics category.

One good thing to come out of the (cursed) (seemingly never-ending) (and yet here I go talking about it) (Stephen Geigen-Miller: part of the problem) SFFnal Awards Discourse is the reminder that there are many awards out there that are worthy of our attention – awards that, because of their mission, focus, and audience, can help bring works to our attention that we otherwise might have missed.

For 35 years, the Lambda Literary Awards (the Lammys!) have honored excellence in LGBTQ+ writers and writing, as part of Lambda Literary’s overall mission.

“Lambda Literary nurtures and advocates for LGBTQ writers, elevating the impact of their words to create community, preserve our legacies, and affirm the value of our stories and our lives.”

( – from the Lambda Literary website)

It’s always a good time to lift up and center LGBTQ+ comics and LGBTQ+ creators, and this feels like an especially good time – and not, sadly, just because it’s Pride Month.

But let’s not dwell on that, just now. Let’s celebrate works and creators that deserve to have their impact elevated, by taking a closer look at the 2024 Lammy Award finalists for Best LGBTQ+ Comics. A quick reminder that, as usual, these reviews contain spoilers. Also, I was shooting for capsule reviews, but there was so much to say about each of these graphic novels that they ended up being pretty big capsules. The books appear alphabetically by title, as they do on the Lambda Literary website, and aren’t ranked in any other way.

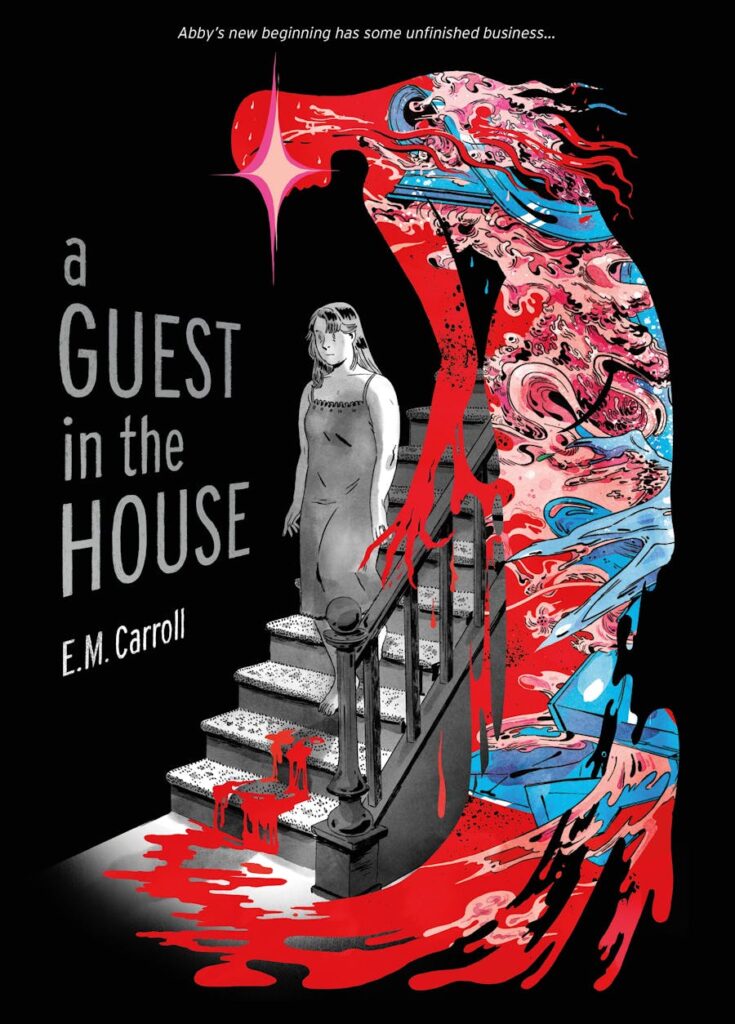

A Guest in the House

Emily Carroll

Published by First Second

A dark, genuinely unsettling small-town Canadian gothic – none of which describes my usual reading. Indeed, I’m still not sure if I exactly liked this new original graphic novel from acclaimed webcomic creator Emily Carroll – but I do know that I’m still thinking about it.

Abby is a woman who’s drifting – not aimlessly, more like a detached observer – through life in a cottage-country Ontario town. Recently married to David, a dentist who just moved to town with his young daughter Crystal after the death of his first wife Sheila, Abby becomes convinced that their beautiful lakefront home is haunted by Sheila’s ghost – and that David may not be as innocent in her death as he says. But Abby’s grasp on reality is fluid at best and it’s unnervingly unclear whether she’s seeing ghosts and revelatory visions or the products of her own unquiet mind. One thing that is clear is that Abby is falling in obsessive love with her husband’s dead wife – or the person she imagines Sheila to have been. Increasingly unmoored, Abby and the story careen towards a bloody conclusion.

Carroll contrasts Abby’s mundane, even banal everyday life, depicted in clear lines in black and white with light grey shading interspersed with pooled shadow, with sudden shocks of vivid color in Abby’s dreams, fantasies, and violent intrusive thoughts. It’s a brilliant use of the storytelling potential of color in comics, and it’s seductively appealing. It’s no wonder that Abby is drawn more and more to the pull of her internal life.

This is, obviously, a deeply ambiguous story. Who is the guest in the house? Is it Sheila, haunting a home she never lived in? Is it Abby, who feels like a guest in Sheila’s life, and in her own life? Heck, I’m still only about 80% sure what happened at the end, given how consumed Abby is by either Sheila’s ghost or her own fractured relationship with reality. Genre readers (like me) will especially be primed to believe in Sheila’s ghost and David’s villainy, but the violent and obsessive intensity of Abby’s visions and dreams belie those comforting assumptions.

This is an intense graphic novel, and an ambitious one. My ambivalence about it is entirely down to the ambiguous ending, which is a device that I usually dislike. But I can’t deny how apt, well-crafted, and effectively employed it is here. This is a powerful long-form debut for Emily Carroll, and I recommend it.

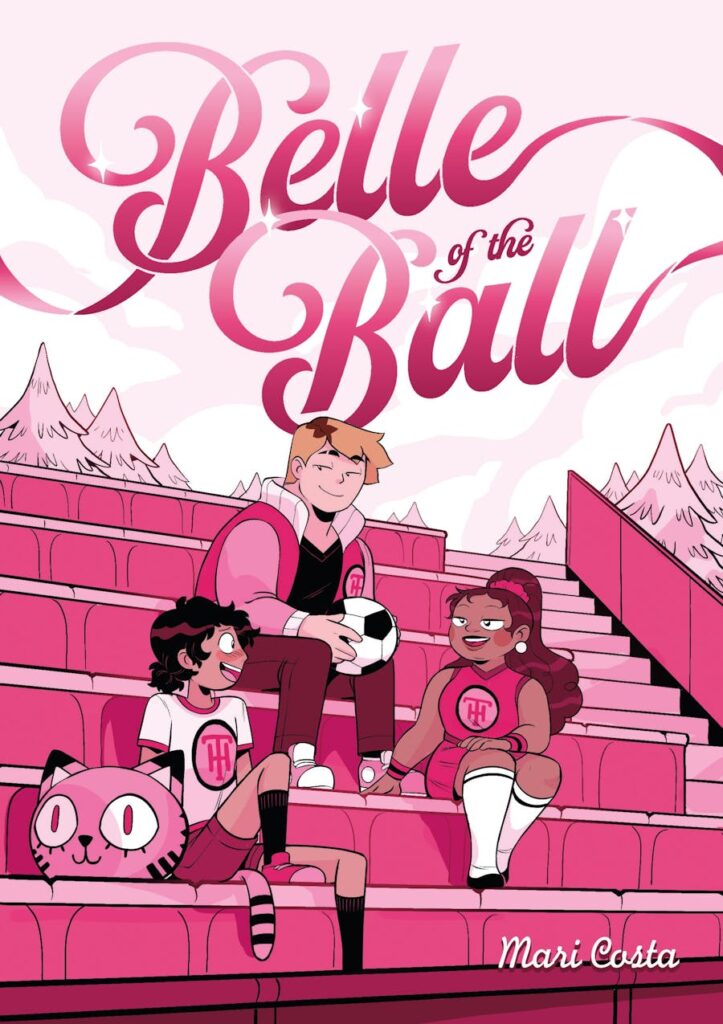

Belle of the Ball

Mari Costa

Published by First Second

Without a doubt the lightest work among the nominees, this YA high-school romance about a love triangle between a popular cheerleader, her jock girlfriend, and the nerdy girl with a crush, who the cheerleader manipulates into tutoring the jock in English to bring her grades up – only to have feelings between jock and nerd ensue – is sweet, frothy, and effervescent. Basically, it’s ginger ale as a graphic novel.

But light doesn’t mean insubstantial. While it’s a confection, Belle of the Ball manages to avoid being slight by eschewing easy expectations. The cheerleader, Regina, is manipulative, yes – but she’s not a mean girl, she’s smart and sometimes kind, and mostly it’s just really important to her that everything in her life go to plan, including her girlfriend having good enough grades that they can both go to an Ivy League school. Chloe isn’t a dim jock; she excels at computer science but has trouble understanding the point of analyzing English literature on a deeper level – and just really wishes her girlfriend would relax. Hawkins, the shy, seemingly introverted nerd, has a crush on Regina, but she’s not creepy about it, and she has an expressive, exuberant, assertive, deeply femme side that she locked away to cope with high school (it’s not really a spoiler that she’s, in name and in role, the titular Belle).

There are no direct SFFnal elements in the story, but it’s charmingly fandom-adjacent. Hawkins writes fan fiction, she and Chloe share a love of JRPGs, and there’s a very sweet – goofy, but adorable – scene between them at a Ren Faire with Hawkins dressed as an Elf Princess.

It is, however, very strongly within the contemporary romance genre, and revels in embracing those elements (although my wife, who reads more widely in that genre than I do, tells me that love triangles are out these days, at least in prose romance for adult readers). It wears its tropes on its sleeve proudly; it has a tight focus on its core trio to the exclusion of other characters; it takes place in a world that’s joyfully free of racism and homophobia (the school’s most popular cheerleader and one of its most popular jocks are an interracial lesbian couple, and literally no one cares – the one time it comes up, it’s because the other cheerleaders tell Regina they wish they liked girls too, because boys are the worst). And, of course, the outcome is fairly predictable as the story unfolds to its Happily Ever After. But that’s the point of capital-R Romance, after all. It’s not the destination, but the way that we get there, and the pleasure in seeing the protagonists resolve the other issues in their lives by resolving their romance.

Costa’s art is gently cartoony, with a discernable but not overwhelming manga influence. The use of strong, clean black-and-white character art with pink as a spot color throughout simultaneously emphasizes the romantic theme, the sweetness of the story, and its celebration of Hawkins’ rediscovery and reclamation of her repressed femme side.

This is a good-natured, happy, fundamentally optimistic story, and I recommend it.

Blackward

Lawrence Lindell

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

Four childhood friends – Lika, Amor, Lala, and Tony, all of whom self-describe as “Black, queer, and weird” – struggle to reach out to build connections and community. First meeting as a club they call The Section in a local community center, their attempts are frustrated by hostility and conflict with less accepting people that ends up weaponized against them. Losing that space, they’re forced to seek other venues, and end up finding the help of the owner of a local bookstore, who helps them find new options for creating connection by creating a zine fair for other Black, queer, weird people – that’s the titular Blackward. A threatened protest against the fair by the same homophobic people who drove them out of the community center throws them off again, but they rally and find that there is a wider Black, queer, weird community that has their backs, that’s been waiting to welcome and be welcomed by them.

The threads of acceptance, community-building, and mutual support are woven throughout, and it’s beautiful. I particularly loved how strongly the resolution rests on solidarity – between queer Black people, and importantly, in intergenerational solidarity as well. The Section teases Mr. Marcus, the bookstore owner, a bit for being clueless about modern technology and because they had to explain to him what a zine was, but he supports them when they need it, and provides essential mentoring and guidance, and they appreciate and support him in return.

It’s funny; I’m probably not exactly the core audience for this book, and I love it. There are some finer details that I didn’t touch in in my summary, because it involves conversations within the Black community – about being queer, or weird, or a nerd, and grappling with elements of social conservatism, homophobia, and toxic masculinity within that community – and as a white guy I’m aware that’s very much not my lane to comment on. But – as discussed in some recent conversations on the socials about a certain producer of animated feature films who shall remain nameless here – there is a universality to the specific here that is deeply engaging.

I remember the days when graphic novels that weren’t from one of the big superhero publishers were restricted to black and white art, except for the cover. But not only do all the Lammy finalists this year use color to one degree or another, they all make it an important part of the art and how the art connects with the reader, and this is no exception. The use of color in Blackward is just dazzling. This is a bright, vibrant book full of bright, vibrant colors, emphasizing art that feels like it draws from both cartooning and street art traditions. Each member of the Section has a signature color, and they aren’t muted at all, reinforcing their bold and unapologetic assertions of their selves and their love and support for one another.

This is a loving and lovely YA graphic novel from artist, writer, and educator Lawrence Lindell that shouts Black, queer, weird joy and solidarity, and I recommend it.

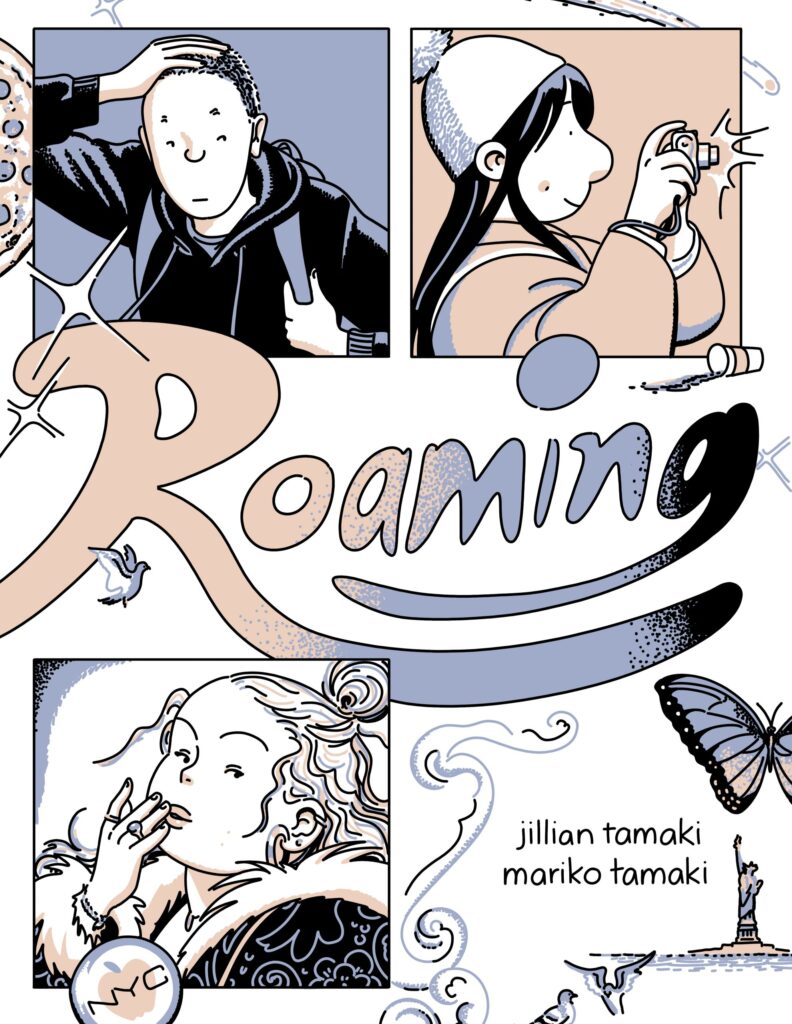

Roaming

Written by Mariko Tamaki

Illustrated by Jillian Tamaki

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

The title is very apt; this original graphic novel by the cousin team of Jillian and Mariko Tamaki is a fascinatingly low-plot meander through five days in the lives of three young women as they explore New York, and as they navigate feelings and issues between themselves that they’re only just becoming aware of.

It’s 2009 and Canadians Dani and Zoe, best friends from high school now attending different universities, are reuniting in New York City on spring break, seeing the city for the first time. Crashing the party is Fiona, Dani’s devastatingly cool art-major classmate. Tensions simmer among the three as Zoe, who’s struggling with her studies as a science major and with trying to find herself as an out queer woman, bristles at the reminders Dani inadvertently brings of her failures and of her time in high school as someone she doesn’t want to be anymore. A connection sparks between Zoe and Fiona, and Dani feels left out of the trip she planned – in painstaking detail – to reconnect with her best friend. The frustrations boil over, and there are fallings-out and fallings-back-in, some awkward sex, some drunken outbursts, some mild drug use, and a lot of museums.

If publishing was still trying to make “New Adult” a thing, this would absolutely have been labelled as a New Adult graphic novel.

This is, as I said, a low-plot and slow-paced story, but that isn’t to say that nothing happens, or that what happens isn’t important. Watching these three young women spark off one another, trying to sort out who they are now and what they mean to each other, is moving and meaningful. The observations of place are keenly detailed – as are the character moments. I went to university over fifteen years earlier (and am a straight white guy), but I remember that time in my life, and those feelings, and I found Dani and Zoe’s struggles and conflicts deeply relatable and touching.

Fiona is less of a protagonist – we see her with Dani and Zoe, but not alone – but as a character she hit me with a profound shock of recognition; if you went away to university, especially (but not only) if you lived in residence, you probably knew someone like her – talented, charismatic, the one that everyone saw as the coolest person in your program, with an entourage of admirers in their orbit. More worldly, seductively sophisticated-seeming. And with a ton of barely-hidden trauma and definitely some undiagnosed mental health issues. I knew young women like Fiona, and like Dani, I found them compelling and was sometimes swept up in their chaotic wakes.

Jillian Tamaki’s art is devastatingly good, with a light yet detailed touch in her characters, an assured ability to establish the finer points of very specific time and place, and a phantasmagoric quality that effortlessly depicts the feeling of being young, a bit unmoored, and overwhelmed by being in a big, busy, vibrant but indifferent metropolis for the first time. The selective subtle pastel hues in the colors somehow emphasize the visually overwhelming brightness of New York City by averting it, while also reflecting the emotional states of the characters.

As an aside… There’s a real vogue for limited color palettes in graphic novels right now, isn’t there? I’m not complaining; all the examples I’m looking at in this column use the approach very suitably, effectively, and with great skill. It’s just interesting to note what seems to be a trend. I remember when suddenly independent and self-published comic books all had minimalist cover art, and when they didn’t anymore.

This is a wonderful graphic novel, full of brilliantly-observed, shining moments, about a brief, seemingly-unimportant time in the lives of three young women that will change them all and never come again. I recommend it.

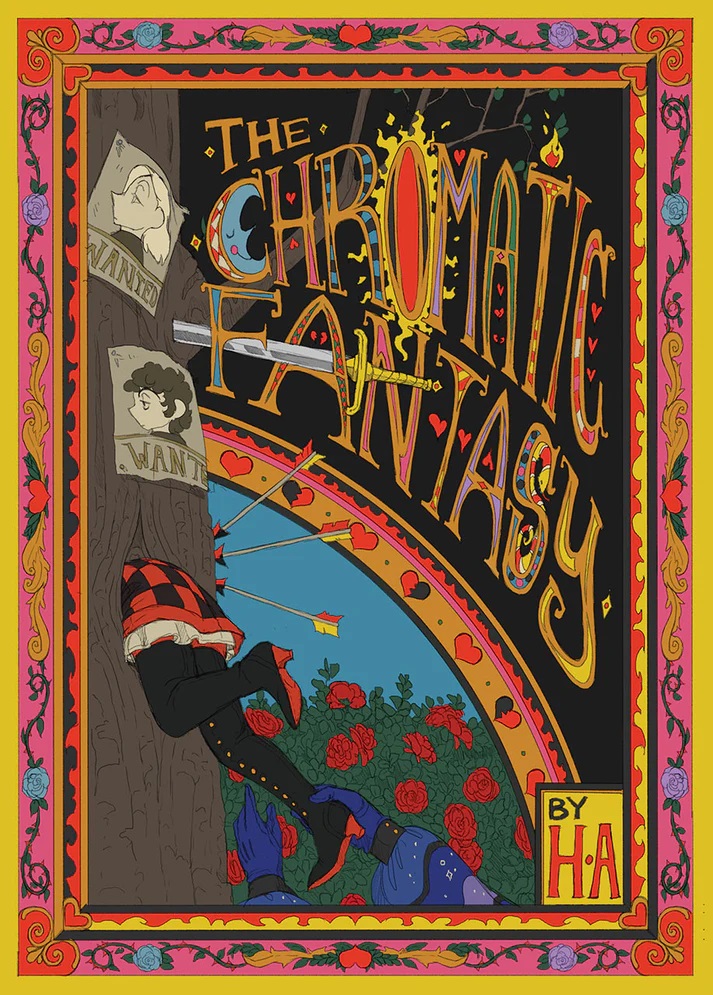

The Chromatic Fantasy

H. A.

Published by Silver Sprocket

In a brief frontispiece, H. A. introduces The Chromatic Fantasy in part by noting that it’s their first completed long-form project. To be honest, I’d have guessed that without the explanation. This is almost the Platonic ideal of a creator’s first, “throw everything I love and that matters to me into the story and just flat-out bare my soul and all my passions on the page” graphic novel.

Jules is a trans man who, with the help of the Devil (actually the setting’s evil God of Fire, but the two terms are used interchangeably within the story), escapes a stultifying life in the nunnery where they’re both trapped. Oh, and they’re sort of in love, or at least obsessed with each other, and having something that’s a bit like sex but more metaphysical and way creepier. So Jules cuts his hair and gets to dress like the man he is, finally, and becomes an outrageous swashbuckling thief.

Also, thanks to a cursed locket that binds him to the Devil, Jules can’t die.

Then, Jules meets Casper, who’s also a trans man who escaped from a constrained life under someone else’s control to live his truth as a man and as an outrageous swashbuckling thief. They have a sword fight, then amazing, non-metaphysical, non-creepy sex. Then they fall in love, team up to do outrageous crimes, and the Devil gets jealous. Jules has visions where he argues with a version of himself who’s a personification of his shame and self-hatred, and then Casper’s past catches up with them…

Yeah. It’s a lot.

It’s also, obviously, a delightfully idiosyncratic and personal project. And it’s idiosyncratic in every way. The art is rough in spots – not amateurish, but scratchy. Some of that is likely to have been a deliberate choice reflecting Jules’ earthy, passionate, and chaotic nature (or possibly a rush to meet a deadline, or both). But H. A. also sometimes doesn’t quite hit the mark in depicting depth of field, perspective, and action – and the latter is an unfortunate lapse in a story with as many swordfights as this one. But the manga-influenced characters work beautifully in emotional moments – and in sex, which comes up a fair bit and is one kind of action that H. A. depicts highly effectively. Watching Jules and Casper delight in falling for one another, and in being in love is an absolute joy – whether they’re robbing a crowd of onlookers at an outdoor performance, eating a meal, talking on the phone, or hanging out at Starbucks (yes, there are some very deliberate anachronisms; it’s arguably silly, but it doesn’t break the story, and it grounds the relationship surprisingly well).

And again, for the fifth time in as many theoretically-capsule reviews, I have to praise the use of color. Obviously, it’s called The Chromatic Fantasy for a reason; the colors are magical, intense and startling. Many descriptions of the book online compare the art, and color specifically, to stained glass and illuminated manuscripts, and I can definitely see that. But even more so, it reminds me of the colors – and in some ways the layout, which might explain the depth of field – of the old Rider-Waite Tarot deck, with its bright, heedless fools, sad, dreamy knights, and collapsing towers.

So yes. It’s a lot. And it’s fun and funny, and it probably tries to fit in more story than was entirely wise, but I loved Jules and Casper and I loved the ride. I’m glad H. A. completed their first long-form project (and I’m left with a sneaking suspicion that they’d be a lot of fun to play D&D with). I look forward to what they do next, but for now, I loved what they’ve accomplished with The Chromatic Fantasy, and I recommend it.

Final thoughts on the finalists

This is a great – and fascinating! – award short-list. Every single one of these works is eminently worthy of the wider recognition they’ve earned by being a finalist, yet they couldn’t be more diverse in their content. I’m very impressed with the panel of judges who selected them – this is a genuinely impressive range of material that they’ve chosen to honor.

The Lambda Literary Awards will be presented on June 11, 2024. I’ll be watching with interest to see which of these wildly different books is awarded Best LGBTQ+ Comic, but they’re all worth your time – and, as is no doubt obvious by now, I recommend them all.