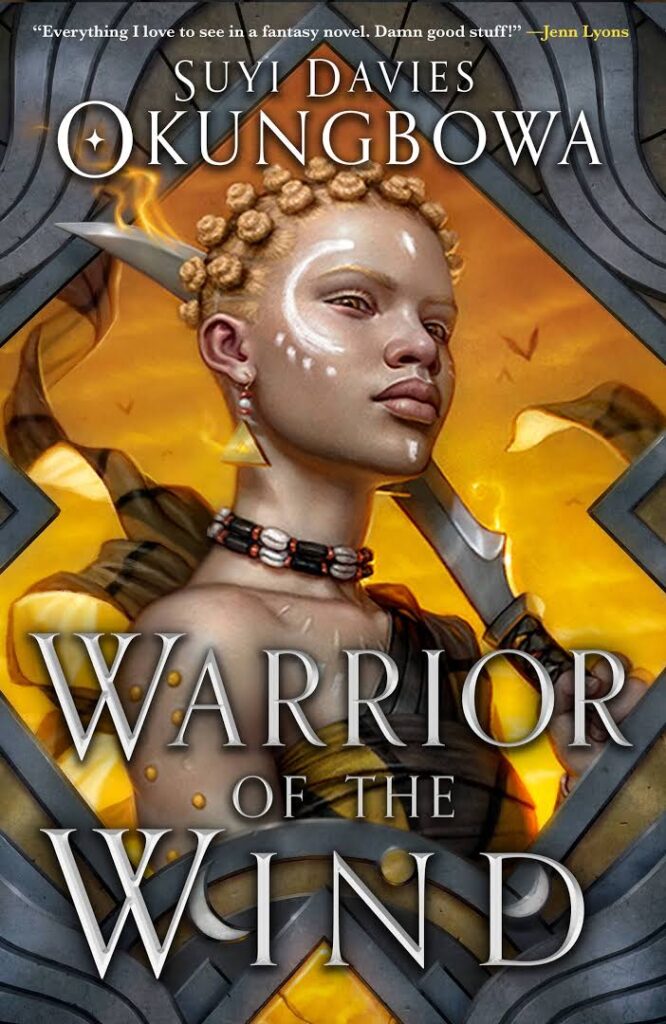

Son of the Storm and Warrior of the Wind are the first two thirds of a fantasy trilogy, The Nameless Republic, by Suyi Davies Okungbowa.

We begin in Bassa, the center of the world, at least to the inhabitants of the city. Bassa is the central city in a peninsula of rich land, the central axis to a number of protectorates and dependencies that the city holds suzerainty over. But even as the city holds sway over this large peninsula, the much larger mainland to the east looms. The Soke mountains tower over the skyline of the city, unmistakable, huge, dominant. The Soke Pass through the mountains, a vital, essential, indispensable trade connection to the mainland, leads to a region of savanna, sahel, and eventually desert. For all that Bassa holds sway over on the peninsula, it needs the trade of the mainland not only to thrive but to survive.

And so, the action of the series, in the first novel, begins with the closing of that vital pass.

Bassa itself is a vision of a fantasy series that, like the cultures, languages, and peoples of the series, is strongly focused on and inspired by the cultures of Africa. Let’s go back to Bassa. Vibrant markets. Mudbrick architecture. The Great Dome as the seat of government. A melting pot of cultures and castes jostling and jangling. Danso, one of our main protagonists in the two books, is of an immigrant caste but he’s a “man on the make”, he is a jali in training, a man of knowledge, or will be. Sure, he can be a layabout, but he does strive for a better life all the same. His journey as a character is one of the central tentpoles of the two novels. But his story begins, and is rooted in, the city of Bassa and what makes Bassa his center.

Bassa’s central location is a hub of trade, in a rich region. This, combined with the cultural notes in describing Bassa, evokes African history. In particular and specific, with drier regions just beyond a pass, with jungles and tropics at hand, this all makes Bassa, to my mind, seem to be very much derived from the Mali Empire, and the city of Djenné in particular.

Okungbowa’s Bassa is not at the height of its power, however. It is a city, a power, that has seen better days, and that decay and slippage helps drive the plot. Part of that slippage is climate change, affecting the entire peninsula and beyond: desertification and changes in rainfall are making the desert encroach westward. Political instability is affecting Bassa, as proud as they openly say that they are the mightiest and best. There is a real theme of reclaiming old glory, of going back to the heights of power and influence lost to time and history.

And this is where we can meet Esheme. Esheme starts off as the daughter of Nem, a politically important woman in the Bassa government. She also starts off in a serious relationship with the aforementioned Danso, even given his immigrant caste status. But Esheme is wildly ambitious and has an eye for the main chance for power. Esheme’s quest for power starts off in esoteric form, as she finds out just what her mother has been doing that caused the pass to be closed that is the inciting incident for the series and the book. Esheme’s discovery that her mother has been using an old, forbidden form of magic, ibor, leads her to seek to use it herself. And once she starts to learn this esoteric power, opportunity and events cause her to seek more temporal power as well.

Central to those events, and to the ibor itself, is the third of our main trio of characters. Lilong. Lilong is from a set of islands that Bassa and most people believe drowned in the seas long ago. The islands are still a going concern, however. In fact, they are one of the few known sources of Ibor. And in fact, it is the theft of an ibor heirloom by agents of Nem, and Lilong’s journey into Bassa to retrieve it at any cost, that has set off the chain of events that started the first book in the series in the first place.

The two novels are, throughout, rich on place details and giving a real feel in the five senses of what Bassa and the world around it is like. As Danso and Lilong find themselves on the run after a murder of a high Bassa official that neither actually committed, we get to see more of the peninsula, and more of the world through the eyes of the characters. Bassa loses its focus, somewhat as the central location for the dramatic stories unfolding in the narrative, in favor of showing us much more beyond it. Okungbowa had been seeding that the jali’s rote memorization and recitation of knowledge really is a stillborn practice that doesn’t reflect current and real realities about the world. It’s the old story of new knowledge is rejected in favor of old collected wisdom, even if the realities are now different. This dry and formulaic learning and transmission of knowledge (such as it is) is a sign of just how Bassa has slipped from its former heights. As we leave the center of power, too, we get to see in the colony/protectorate of Whudasha, and elsewhere, just what the rest of the world thinks of Bassa, and those reactions and considerations of Bassa help form our perceptions of the various places seen in the two novels.

I really enjoyed the immersive details of Bassa as a city, as we see it in the first novel. It feels like a rich and vibrant fantasy city whose antecedents and inspirations and touchstones are not the same ones that are in most western fantasy. Or, if we ever get to see such places in most western fantasy, they are the “exotic foreign place” that gets a shallow look at, at best. Here, in these two novels, much like, say, Evan Winter’s Rage of Dragons series, we get such a place as the center, as the standard, as the benchmark against all else as described and measured. This goes way back to my 2014 essay on fantasy beyond the Great Wall of Europe and a 2023 follow-on essay at Apex Magazine. So by having it as the center, the standard, the focal point, Okungbowa can really get a sense of the people, power and politics of this African-inspired fantasy world by having such a place as its default.

And speaking of power, the two books really feel like to me a study and critique of decaying imperial power, and what happens when that eroding power slips to the point where the imperium is visibly decaying, and starts to overcorrect and do truly shortsighted and ill-advised things in the quest to not only maintain the decaying status quo, but to reach back to a mythical golden era before that never really existed in the first place. Even before, but especially once Esheme grabs the reins of power, this is a theme that really comes through in the two novels. The author is not kind about what happens to the imperial project when things start to slip, and the two novels written so far could be considered as the slow-motion fall of Bassa. And possibly, if I read the tea leaves of the novel, the birth of something better. Or at least the hope of the birth of something better. And rebellions, as we all know, are built on hope. This novel embodies that ethos quite fully.

But it’s interesting to me how my own experience can interpret and look at events in a book that are in a wildly different culture and setting and my mental models reach for the familiar. At one point, an area of the city in revolt starts setting up barricades and trying to protect itself and choke the life of the city. If you are a westerner like me, you may be thinking, as I did in these scenes, of the 1832 barricades against the French Monarchy erected by the Commune of Paris (and seen in literature and theater, in Act II of Les Miserables). I don’t know if there are models in line with the African heritage and cultural richness seen here, but this is where my mind went. The actual results play out, however, rather differently.

While I strongly enjoyed the first novel without much reservations, there are things I didn’t like about the second book in particular, and that revolves around Esheme. It is rather spoilery to say, but given the nature and need for content warnings, this is a content warning that I feel should be in this review, so I can discuss it, and that you as a reader can come to deal with it and understand it. Esheme learns, in the course of events, that it is not she herself who is able to wield the red ibor, but it is the fetus growing inside of her, a product of a union of an immigrant to Bassa. Just as Danso is able to wield the red ibor because of his Shashi (mixed blood nature) heritage, Esheme, by all standards a native pure born of Bassa, is able to do so because of her pregnancy of a Shashi child. The dangerous nature of red ibor, however, means that the fetus is necessarily dying with every use of the power. And Esheme clings to her power by heavy use of the red ibor. It is too-casually mentioned for my taste that in the third book, Esheme is on her third pregnancy, so that she can continue to wield that magical power that allows her to keep her social and political power. While there are trigger warnings at the beginning of the book, this made me feel uneasy.

One other thing readers who have not started the series, or have only read Son of the Storm to date should know: In this second book, Okungbowa has chosen to take some minor and even major characters off of the board. I have not gone into the rich set of secondary characters outside of Esheme, Danso and Lilong (aside from a mention of Nem), mainly because I could write a whole piece and essay on the intricate and fascinating web of characters with which the author peoples his world. Loyal and not so loyal retainers, power brokers, revolutionaries, failed leaders now eking out a living, and people just trying to run an important trading post and inn don’t even scratch the surface of who we meet in the pages of the two novels. Some of them do get viewpoint chapters in typical high fantasy fashion, others we only see through the eyes of others. But all of them come to life off of the page and are bent by the narrative. But one should know that in the second book, Okungbowa does take some secondary and even primary characters off of the map. I am not quite sure where the author is going with this, whether this is a “changing of the guard” or going for an even more ambitious epic that spans more than a single set of POVs start to finish.

What I am sure of is, is that I want to find out.

3 Responses

Warrior of the Wind picks up where its predecessor left off, following Dedan and his companions as they face even greater challenges. The stakes are raised as they delve deeper into the mysteries of the Nameless Republic, uncover secrets of the past, and confront a formidable foe who seeks to reshape the world.