Until very recently, science fiction and fantasy had a predominant flow of cultural borrowing that generally went from non-Eurocentric cultures, to America and Britain. This started with the idea of orientalism and places beyond the metaphysical Great Wall of Europe, if depicted at all, being done in an exoticizing fashion most of the time. As science fiction and fantasy has brought more global voices to Western audiences, that of course, has changed. We are now getting plenty of fantasy from beyond that Great Wall, from Africa and particularly from East Asia. Borrowings of tropes from Africa and East and South Asia have been moving toward more nuanced and less problematic directions on the whole.

But culture is never a one-way street. The world is not a game of Civilization where one country’s dominant culture overwhelms all others. There is give and take, and cultures borrow from each other all the time. And in this day and age, it seems logical that we can and will find Western SFF tropes in science fiction and fantasy written outside the West. But given publishing, such stories have been not easy to find or read in the West until comparatively recently.

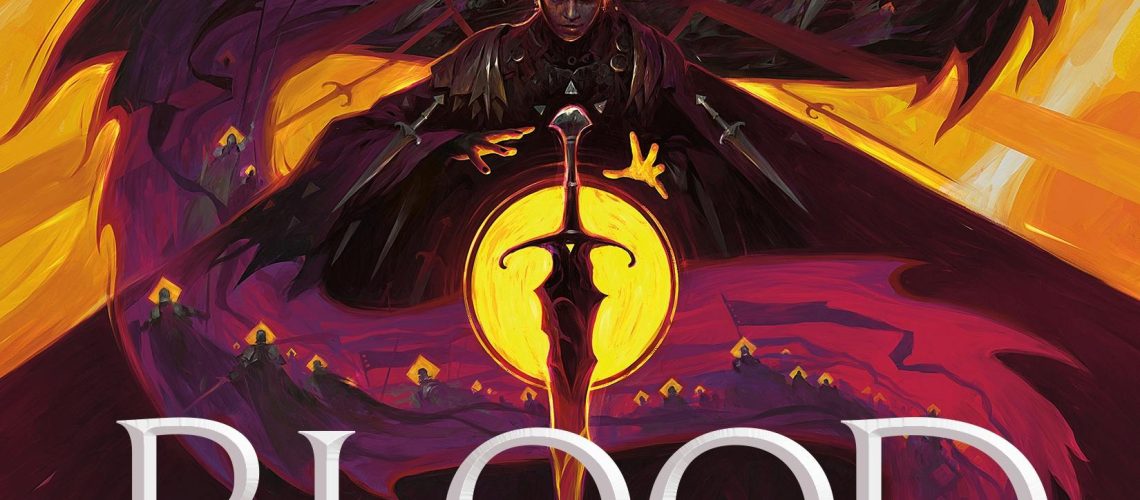

And so we come to Blood of the Old Kings by Korean author Sung-il Kim, translated into English by Anton Hur. It might look at first like just a typical epic fantasy novel, but a closer read reveals something rather different than you’d expect, even by the standards of modern fantasy epics.

At its heart, Blood of the Old Kings is a story about Empire, reactions and resistance to it. Our three protagonists are all in their own way taking up the mantle of resistance to that Empire. But before I even get to our protagonists, I want to follow the thread of my opening here and talk about the Empire itself. Going in, knowing this was translated from a Korean author, I was expecting the Empire to take all of its cues from East Asian models, of which there are plenty. And while there are definite notes of this (the system of training sorcerers feels a lot like Ming-era Imperial Examinations as one example, the nature of Dragons in this world another), there is a lot more that harkens to another model.

Consider that the military units of the empire are called Legions, and are described in gear, armament, and style as such, including military ranks such as Centurions. Garrisoned fortifications, punitive expeditions against unconquered people, vassalized Kings on the borders. The Imperial project of ever expanding outwards. Legates and provincial governors.

What Blood of the Old Kings feels like, then, to me, is that reversal of the old tropes. There are plenty of novels and D&D modules and whatnot that depict Empires, kingdoms and polities that, to one degree of accuracy or another, resemble Imperial China, or Japan or other kingdoms in East and South Asia, or take their notes strongly from such models. Here, Sung-il Kim, a Korean writer, is doing what I have been far less exposed to (and now I wonder how prevalent it is), and has taken substantial Empire building blocks from the early Roman Empire.(1) What the novel provides for me is seeing how something that is part of my background (in the loosest of senses), or part of the Western Tradition (in the Eugen Weber sense) and seeing how other cultures take those ideas, and remix it with their own. It gives me, as a reader, a window into what someone in Korean thinks of when they think of the Roman Empire, if at all. This is a perspective (in a broad sense) that has been very lacking in science fiction and fantasy, and Sung-Il Kim’s book gives us that opportunity to see it in action.

So we have an Empire that takes a lot of notes from the Roman Empire. Opposing this empire, in the novel, we have three points of view, three foci of resistance, in their own ways. Cain lives in the Imperial capital. He is from the conquered Kingdom (now province) of Arland, originally, but he has made a life in the capital ever since with odd jobs of various sorts. He is very well connected, and so it is no surprise that when he starts investigating the death of a friend…the imperial secret police come investigating him in turn. His story and his role in the narrative is much like a bridge or connective tissue between the two more driving forces of the narrative.

Arianne is a student at the Imperial Academy, learning to be a sorcerer. In the empire, active sorcerers aren’t useful, or even taught spells, but dead sorcerers as power sources are. Arianne’s stint in the academy, you might imagine, is not voluntary. And the academy definitely would be alarmed to know that she has the spirit of a dead sorcerer, Eldred, inside of her. Eldred is from a time where sorcerers did actually wield magic, especially against the Empire that now has his body as a power generator. And HE has a plan.

Rounding out our point of view characters is, arguably, the lead heroine of the novel, Loran. Like Cain, she is an Arlander, but she lives in the conquered and devastated province. Hers is the most straight-from-the-barrel form of revolt and revolution; she wants Arland free, and in the first chapter walks into a dragon’s lair to try and find the power to do it. What she finds…is that she herself is a hero. Loran, I feel, gets the best character arc of any of the characters. While plenty happens to Cain, and Arianne finally makes moves to stand up for herself, it is Loran who goes on the longest and most detailed of what we might consider a classic character arc. Time and again, she is sorely tested and slowly pushed into accepting that her role is indeed to be a leader, with all the costs and responsibilities thereof. Her story is learning not only to pick up the mantle of leadership, but also not to put it down again.

I’ve mentioned how the novel borrows from Western Epic fantasy, but I want to mention something it decidedly does not borrow. There is a strong, perhaps even still dominant strain, in epic fantasy that is either outright Grimdark or is Grimdark-infused. Morally grey protagonists. Societies and cultures where we substitute one bad situation for a slightly less bad one, Dystopian, amoral and endlessly violent societies and characters. Heroic bright fantasy is still in the shade to the Grimdark mindset. Here, though, in Blood of the Old Kings, Sung-il Kim’s protagonists are conflicted about what they do, and wonder if they can make a difference, but they are decidedly not morally gray at all. So, readers who do prefer the Malazan end of the epic fantasy pool (decidedly a large portion of the fantasy readership, it seems) may not appreciate the more earnest heroism of the novel.

One last thing I do want to talk about, non-spoilery if I can, is the plotting toward the ending. We have the three characters working toward their own goals, and slowly becoming aware of each other and their needs, although it’s not quite a meshing together of forces. Loran’s response to the Empire as noted is the most traditional anti-Imperial, Arianne is just trying to survive her nature as a sorceress (and soon finding a bigger threat), and Cain starts off investigating a murder, and winds up in the coils of investigations and plots across the city and beyond. The result of the climax of this book feels realistic, although narratively it does not feel like what a reader might expect or even want for the result of the climactic confrontation. But it feels grounded in this world and in the realm of the possible, and opens the door to future novels and a continuation of the story. It does, though, thus mean that it’s not all that satisfactory a stopping point; it’s not as good as an off-ramp as it might be.

Overall, I found Blood of the Old Kings interesting and entertaining, even if it wasn’t always what I was expecting out of a fantasy novel. Once I saw that the author was taking tropes I had long internalized and seeing them through a new lens and infusing them with ideas of his own, I was engaged with them, and how the characters were inserted and worked inside of his fantasy world.

- With a few notable exceptions, most depictions of Empires in the Roman Empire mold show it in its ascendancy or in a stable state. You get far more grasping or powerful Empires being opposed by rebels and partisans on the margins than say, an Emperor who is a “barracks Emperor” holding onto power by any means fair or foul. In Roman Empire timeline terms, this means you get plenty of stories in a first or early second century AD model. Your Emperor in these stories are modeled on Augustus, or Trajan, or if you want to show decadence and evil, a Commodus or Nero or Caligula. You don’t get many depictions of an Empire with a figure like Diocletian, trying to rebuild the Empire, and you rarely get anything like the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, or the warlord dominated Emperors of the end of the Western Roman Empire. You get a skip forward to the intrigues of Byzantine politics, but again, a stable Empire even with revolts and divisions.(1a) As our depictions of Empire as an idea have been more critical of Empires and cast them as destructive and negative forces, Empires themselves usually seem to be seen as more evil…and also more stable and stronger while doing their evil. I think there could be a worldbuilding bit here, with a Romanesque Empire lashing out, even its weakened state, and heroes rising to oppose it and its tyranny.

(1a) A podcast episode of “Byzantium and Friends” (a podcast about Byzantium) discussed depictions of Byzantium in fiction: [https://byzantiumandfriends.podbean.com/e/119-byzantium-in-science-fiction-fantasy-and-horror-with-przemyslaw-marciniak/] And it does seem to cluster around a few periods in Byzantine history.