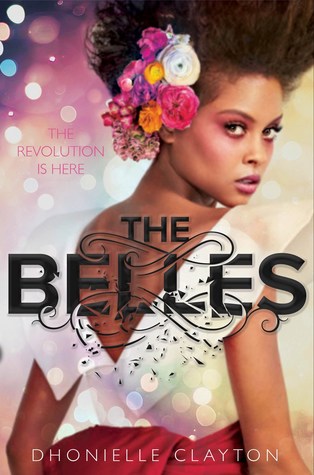

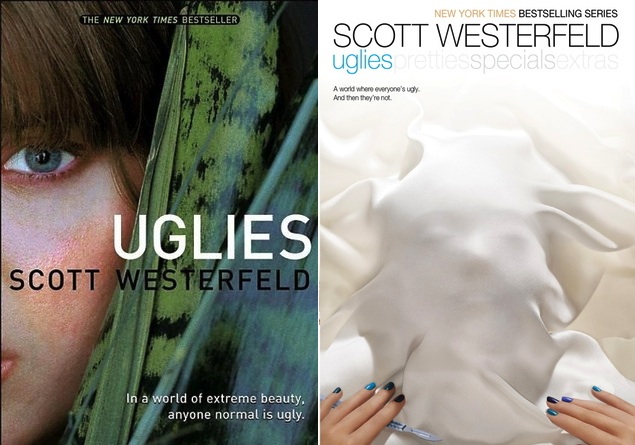

Since the launch of The Belles earlier this year, Dhonielle Clayton has been very open about taking inspiration from Uglies by Scott Westerfeld. The two books form an interesting dialogue, with The Belles building on the foundation formed by Uglies while bringing a somewhat more nuanced and feminine perspective.

The two books share a focus on beauty, with each building a different culture around it. The Belles takes a fantasy angle: the people of Orleans are cursed by the gods to look ugly—with grey skin, red eyes and hair like rotten straw. They rely on the Belles to magically change their appearance into something beautiful. Exactly what that looks like changes from season to season, and these treatments eventually wear off, needing to be renewed. Camellia Beauregard hopes to be chosen as the Favourite of the Queen of Orleans and serve as the foremost Belle in the kingdom. However, she soon finds the reality of the dream is not quite what she expected.

Uglies is a post-apocalyptic sci-fi where the surviving human population lives in cities. On reaching the age of 12, each person becomes known as an Ugly and is segregated until their 16th birthday. At this point, they are old enough to undergo the operation turning them into a Pretty and are moved into the heart of the city where they party hard. Tally can’t wait to become a Pretty and rejoin her older friends. Then she meets Shay, who doesn’t want to become a Pretty. When Shay runs away to join a group of rebels, Tally is given an ultimatum by the forces who run the city: find Shay and the rebels or stay an Ugly forever.

Both books are the start of a series, but I have chosen to focus on them as individual books… largely because the sequel to The Belles isn’t expected until next year.

Both Camellia and Tally aren’t the most likeable characters to begin with, thanks to their investment in the status quo. Camellia is competitive and jealous, determined to win the position of Favourite over her sisters. And Tally fantasizes about what she’ll look like as a Pretty and what things will be like once she rejoins her friends; she’s so deeply mired in the status quo that she feels threatened by the new worldview presented by Shay and lashes out on occasion.

Of the two, Uglies pushes back harder against beauty standards. Although Tally is keen to become a Pretty, the story works to undermine this as a desirable state. The opening sequence shows Tally sneaking into the city to visit her best friend, allowing the reader to see the frivolous, vapid life of the Pretties and how they treat Tally once they realize there’s an Ugly in their midst. Later, the beauty of the Pretties comes to be associated with a curbing of intelligence, making them gorgeous sheep.

This development left me rather uncomfortable and allowed me to develop a greater appreciation of what was done in The Belles. It never pits beauty against brains. Camellia is a little oblivious from time to time, but she’s not stupid and is capable of putting together the pieces of what’s going on by herself.

Also, while there’s absolutely a darkness living under the surface of the culture of the book, there is also a celebration of aesthetics. Camellia takes genuine joy in creating beauty, and thinks about the trends she wants to promote. Her joy is also reflected in the language of the book, which revels in its descriptions of decor, fashion and food. Given our world all too often devalues whatever might be tied to girls and young women, this aspect seems retrospectively important.

Each of the books has different strengths in terms of inclusivity. The Belles puts a woman of colour front and centre—quite literally on the cover—as the pinnacle of beauty. It’s an important choice in this fictional world where skin colour can be changed at the drop of a hat–making race unimportant to the story, but still valued by the author.

However, this same system of using magic to change appearance also serves to raise class issues. The Belles are the only people whit this ability and they don’t work for free. As the privileged elite, the Queen has her own personal Belle–the Favourite–who may, when time permits, also see other nobles who can afford the fees. Everyone else must see the Belles who work in the Houses. Citizens who can’t afford the treatment soon find themselves reverting to their natural grey skin tone, making their impoverished state clear to those around them.

Unfortunately, The Belles does less well with gender and sexual orientation. The Belles themselves are exclusively women, while Scott Westerfeld’s Pretties become so regardless of gender. Plus, the one queer character in The Belles meets an unhappy end in a way that I found very disappointing. Uglies entirely omits queer characters along with issues of race and class. And perhaps unsurprisingly, given the West’s attitude towards weight, neither book does much to support fat positivity. While I recognize not all books can be all things to all people, these flaws represent missed chances to push back at current beauty standards in an even more radical way, and I hope I might see these oversights corrected in future books.

Not that I suggest throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Both books remain interesting stories worthy of reading. The Belles is a lush fantasy with some delightfully Gothic undertones mixed in with its French fairy tale aesthetic. And Uglies remains a sharper story of friendship and betrayal, spiced with more overt danger and adventure. These books might take very different approaches to their material, but both are needed.

One Response