Last year, I read a debut author’s space opera that was hyped by many as the Next Big Thing. Comparisons to Dune were explicitly made. The text showed that the author clearly was writing in conversation with Dune, trying to catch that magic about a big broad space opera by focusing on the life and times of a protagonist destined to have an enormous impact on their universe. But for me, that novel fell down on a number of fronts and was an enormous disappointment.

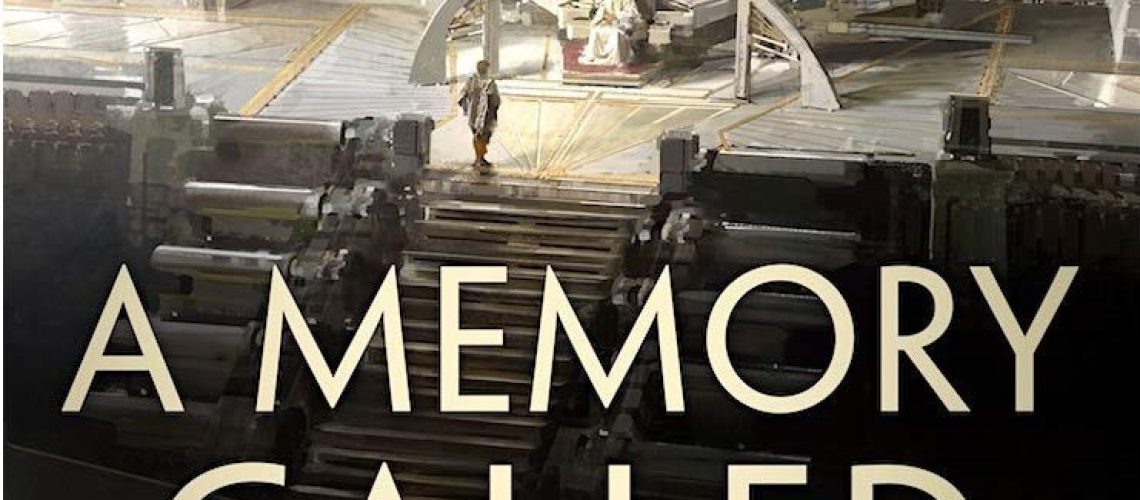

This is not that book. This book steps into those shoes, attempting to capture that Dune magic, and walks miles in them. And for me, it succeeds where that other novel failed. This is A Memory Called Empire by debut novelist Arkady Martine. A Memory Called Empire is a dazzling space opera involving a Byzantine plot that immerses the reader in a fully realized world with a cast of interesting characters.

A Memory called Empire follows the story of an ambassador named Mahit from the small space station Lsel who travels to the heart of a galactic Empire to replace her predecessor. Her predecessor, it so happens, has perished in the course of his duties — a murder, in fact. In trying to find out who killed her predecessor, Mahit gets wrapped up in the tendrils of Imperial politics, with the fate of not only her home, but also the entire empire on the line.

If you aren’t going to headhop around, focus on characters in a traditional narrative manner, and stay with the protagonist throughout, you need a central figure to hang your story on. Enter Mahit, an ambassador from tiny Lsel Station (population 30,000 souls). Even though she has studied the language, customs, and society of the Station’s huge neighbor, she is in for one hell of a culture shock. Luckily for Mahit, she has a cultural liaison in the personage of Three Seagrass (Teixcalaani names are composed of a number, and a noun). Together, Three Seagrass, Seagrass’ longtime friend Twelve Azalea, and Mahit make a trio who set out to tackle the novel’s pressing plot problems.

What happened to the previous ambassador that they needed to send for a new one? Can Mahit keep the station from being absorbed by the Empire? And can she survive what looks like to be the opening moves in a civil war? Additionally, Mahit, like her predecessor Yskandr, is swept up in the orbits of very powerful people — and subsequently becomes a target herself. The author does a great job at developing Mahit as a character and at developing her story. This allows Mahit to resonate and play off of her two companions. It’s a classic way to introduce readers to that rich world mentioned above, and it works. Mahit definitely goes through changes by the time we get to the end of the novel.

Let’s talk about that rich world. The action takes place on a planet simply called “City.” That is, after all, what it IS. City is the home capital planet of the Teixcalaan Empire. The planet is an ecumenopolis, a city that spans a world, just like Trantor in Asimov’s Foundation series or Coruscant in the Star Wars universe. A city as a planet gives this novel a far future urban aesthetic, and it feels grounded and familiar. This is not a Blade Runner or Fifth Element style city of air cars; this is a city of subways, rail transportation, and varying urban densities. Frankly, as an expat New Yorker, I could see the City as New York, from the dense heart of Manhattan to the hills of Staten Island and networks of public transportation as the primary way people get around. The Palace, a central sprawling structure at the center of the city, is in and of itself almost a city on its own, showing a fractal quality to the world that Martine has built.

At a high level, the politics and social structure of the world that the author creates can be summed up as “The Byzantine Empire, in Space!” This dovetails with the author’s training as an expert on the Byzantine Empire, which comes through the details of her created world. The world that she creates features ornate and complicated politics and a highly literate and literary culture obsessed with allusions, poetry, wordplay, and beauty. The inhabitants of the City have an omphalos sort of viewpoint: the city is OF COURSE the center of the entire universe; why would you even think otherwise? The empire is full of deadly and sharp bureaucratic maneuverings. Their schemes and intrigue fill the novel and provide most of the plot elements that drive the narrative. This is not a space opera that has giant space fleets with silicon ray weapons blowing up planets. However, this is a novel where the characters actions could very well propel fleets across star systems. Or their actions might cause a planet sized city to roil in protests and violence.

The novel also does interesting things with languages, translation, transmission of knowledge, technology and lots more. Having a main character from outside of the empire, for whom their language and culture is not native, gives us an outside-in perspective on the concepts of the empire, how its language works, and how someone not raised in it might come to understand the nuances of its language and culture. I didn’t even mention that Lsel Station has neural technology allowing for the transmission of whole personalities that the Empire does not have. This is a technology that has a major impact not only on Mahit’s life (and on the narrative), but also on the idea that technology could transform the Empire as well. This technology, as it turns out, is a major strand of the plot. Above and beyond having a Space Opera setting, this neural technology — its implications and its uses — is among the most speculative elements the novel has to offer. And in a tribute to the worldbuilding, it makes sense why Lsel Station needs and makes use of this neural technology. Worldbuilding informs technology which both inform plot, and they all inform character and back around again.

The writing is amazingly excellent for a first time novelist, and I can see how the author poured blood, sweat, and effort down to the line level to make all of these elements support each other. Too many space opera narratives I have read have rely on walls of words to support the superstructure. The novel is thick, but it is also intricate, fractal in its complexity, and infused with the ethos of the novel and the culture of the empire. There are bits of poetry here, given the poetry-mad citizens of the Empire. Every chapter has epigrams to bring more information to the reader than the tight POV on Mahit will allow. That tight third person limited focus on Mahit does distinguish it from Dune and its endless headhopping (and I think that the Empire depicted that way would be impossible to really render effectively).

About the only negative thing I really have to say against the novel is that the external threat seems a little too distant. That thread is more present and problematic in the aforementioned epigrams than it does to Mahit — or even as a threat to the Empire itself. This may be a function of the very Byzantine concept of “The City is the World” that the novel embodies. All that truly matters is within the City. But putting that aside, everything else in this novel just is incredibly immersive. While following Mahit’s journey into the city, I had the same feeling I got when I first read Dune in the 1980’s, Jaran in the 1990’s, or Pandora’s Star in the 2000’s. That is to say, the feeling of immersion into big wide space opera, interesting and well developed cultures. Language, food, idiosyncracies and peculiarities of culture, and much more create a complete and well realized world.

So, in the tradition of the culture of City and the Teixcalaani, I offer a humble verse:

A Memory Called Empire achieves a Trompe-l’œil effect

An immersion of the reader into it’s world, most potent affect

A completely realized world, a full view around with no defect

A City, a world, an Empire Martine brings the reader within.

That immersiveness makes me imagine that I, too, could step into the Empire and find it entirely real in all directions around me. Even when I am now as a reader am far more interested in character and theme than I used to be, completely enrobing worldbuilding in a novel gets me every time. I fell deeply into this novel because of its worldbuilding, and I stayed for its intricate plot, its well done characters, and its wonderful writing.

Well done, Arkady, Well done.

Now will you give me a Teixcalaani name, Arkady? 😉

A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine is published by Tor Books. It is available where all good books are sold.