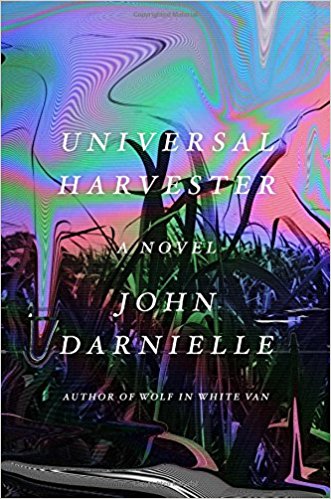

I have to admit, I’m a sucker for a glorious cover. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with flying in the face of the old adage “don’t judge a book by its cover” in my opinion, especially when it’s for John Darnielle’s Universal Harvester, a glorious anodized looking thing which calls to mind a washed out ’70s psychedelic vibe, the colors layered over a cornfield ready to be shorn of its produce. Strangely haunting, one look saw Universal Harvester make its way onto my Amazon wishlist almost before I’d read the synopsis. It also helped that the novel is the second by John Darnielle — brainchild behind the Mountain Goats, whose work I admire — though I must confess this is my first foray into his literary work.

Universal Harvester follows Jeremy, a motherless 20-something guy working at a video store, with little desire to move on. He has a quiet life and an unassuming relationship with his dad with whom he still lives, eating tacos and chilling out with beers, comfortably watching films together. It all seems to suit him just fine. This quiet life of Jeremy’s is disturbed, however, when during one of his shifts at the store a woman returns a video, which she mentions cuts to another movie halfway through. The spliced movie — or movies, as it later turns out — are unsettling; images of people with sacks over their heads standing on one leg, or lying in a heap, the videographer rarely shown but always present, their breath casting an eerie soundtrack to the footage. Jeremy, along with store owner Sarah Jane, don’t want to get involved with the tapes, fearing what will happen if they do, but quite rightly can’t seem to get the images out of their heads. Should they risk their quiet lives to find out what how the tapes came to be, or ignore them and stick with their peaceful lives?

You could expect, from this set-up, that Universal Harvester is a creepy found footage tale where the horror no doubt lies within the spools of tape. There is an obvious comparison to be made with The Ring, but this connection stops past a superficial level. Whereas The Ring’s narrative bears a sudden harbinger of death, or at least starts the protagonists on the road towards a spooky end, the tapes in Universal Harvester lurk on coffee tables and in dens, allowed to play on the characters’ — and the readers’ — minds as normal life continues around them.

“This thing had been sitting on her coffee table at home for several days, like a snake in a houseplant.”

Universal Harvester isn’t a horror story in the traditional sense. There are no jumps to leave you hiding under the covers, but rather a quailing dread, an existential horror, which invokes as much fear as your standard ghostly tale. It is a novel primarily concerned with the self, community and one’s place within, loss, and the creeping dread that comes with the slow advancement of time. It’s the 3 AM fear that keeps you from sleep way after the shock of the movie has worn off.

The novel is also a story about family life, about the impressions your family leave on you and how loved ones shape you. A story about loss, about finding your way in the world when an intrinsic part of you is suddenly taken. In this quiet sadness Universal Harvester shines, this aftermath of a loss that will never quite heal.

“You don’t think about how you really have your whole life planned out until a part of it goes missing suddenly one day.”

There is a preoccupation within horror with the sleepy backwater town, the place that time forgot, where everyone knows everyone else’s business and the scariest thing about the place is the creeping, mysterious notion of change. The video store is losing business to larger chains and with it the way of life that had been so comfy for people for so long. Soon after the internet becomes a fixture in people’s homes, ending that era of unknowability, of societal knowledge learned not through Facebook but through real life friends and the community. That gossip that once united a physical community now moved online, with it losing some of the closeness of those neighbors down the street. Darnielle masterfully realises this small town mentality — both the good and the bad aspects — and uses this to create a story that is as much a feeling as it is a narrative, just as a small town is a way of life rather than an abstract construct. As the novel winds its way towards its zenith, a resolution of sorts is revealed but though rather than a Eureka moment the reader finds that the explanation suddenly dawns on them, as Darnielle expertly knits the story together.

Darnielle’s writing is wonderful and suspenseful, almost King-like in its cadence, bringing to mind his slower moving novels like Desperation. The meandering, non-linear narrative is reflective of the slow pace of life in the towns he writes about, and descriptions of cornfields and silos allow Darnielle to really show off his incredible style. What I did find a little jarring though was the flicking between first and third person narration. Our unreliable, yet all knowing narrator, who seems to me to be at times different people entirely, seems to pop in with that cool voiceover of yore which utters “but things were not alright”, before laying down some new horror. Darnielle also uses the narrator to explore possible alternate timelines, which feels very much as if he’s apologizing for leaving plot holes exposed, offering just a taste of what could have been a more fully-rounded novel.

After I finished Universal Harvester I admit I was left unsatisfied by these plot holes and quietly disappointed that, although I enjoyed the writing, I wasn’t given what I expected from the synopsis. In the time since, I’ve found myself wondering about those loose ends, about the meaning behind Darnielle’s words while cleaning my teeth or washing the pots, and I think therein lies the success of this novel. It’s a rumination of life, loss, the places we call home and how we fit into them, that is meant to be thought on, approached from different angles and allowed time to settle, or rather, unsettle. While there are still disappointments for me, Universal Harvester will remain on my mind for a long time to come. Maybe I need to take a leaf out of the books of those backwater towns and sit and think awhile more.

Penny Reeve is the publicity manager for Angry Robot Books. You can see more of her thoughts here on Twitter.