So on some Autumn morning

Look into the frosty pool.

You’ll see in your reflection

That you’re a Flutterby too!

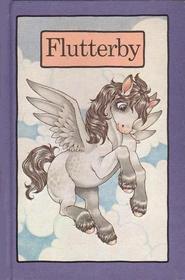

This is a bit of an odd review, but as I was looking through my bookshelves I happened upon one of the most precious books in my collection, Flutterby, written by Stephen Cosgrove and illustrated by Robin James. It is so worn that I have no idea what color it started out, the pages are torn and marked with scribbles, and the title page is adorned with what must be one of my earliest signatures (and also the name of my best friend in kindergarten). Flutterby is such a delightful story that you can’t help but be charmed by the miniature Pegasus that desperately wants to figure out who she is. I turn to it whenever a child comes to visit, because the message is simple, but powerful, and accompanied by colorful illustrations. But Flutterby is only one such story in the long line of Serendipity Books, a series that began in 1974 when Stephen Cosgrove wanted something beautiful and affordable to read to his 3-year-old daughter.

I honestly don’t know how old I was when Serendipity Books first entered my world. I imagine I was quite young. My mother taught kindergarten, so she had access to a great many affordable children’s books. The Serendipity Book series, including Flutterby, are primarily about real animals, but many of them are about other, more magical creatures. More importantly, each story has a moral. These morals are rarely specifically spelled out. Instead, Cosgrove usually wove them into simple poems at the end that acted as reminders for what had happened in the preceding pages. For Flutterby, it’s the reminder “that you’re a Flutterby too!” because Flutterby learns, over the course of the story, that she is unique and should just be herself (no, the irony of the moral vs. the word choice in the poem is not lost on me).

There are a total of 70 books in the series, covering everything from the importance of protecting the environment to confronting prejudice, and what always struck me as amazing thing about these books is that they do not shy away from tragedy or discomfort. Morgan and Yew, for instance, is the story of a unicorn and his best friend, a sheep named Yew. But Yew is jealous of Morgan’s beauty and, in a moment of desperation, basically decides to kill his friend in order to become beautiful. It’s nowhere near that messy in the story as the deus ex machina just poofs Morgan away, but it’s a tragic decision that Yew regrets instantly. In Morgan’s origin story, Morgan Morning, we learn how a young Morgan (who starts out a horse), disobeys his mother, essentially falls to his death, and is only saved when he’s turned into a Unicorn, though he’ll never be allowed to rejoin the land where his mother dwells. I am not even lying when I tell you how much these stories had me crying.

Robin James’ art is an absolutely magical accompaniment to Stephen Cosgrove’s uncomplicated, but often dark, fables. Many of them inspired by Robin herself, which is probably part of the reason that the Morgan stories, at least for me as a child, felt very familiar. This is particularly true of Morgan Mine and Morgan and Me. The protagonist is a princess that lives in the Land of Later. The Land of Later is an abandoned kingdom, containing only the princess and her aging father, the king. But what makes the princess so absolutely perfect is that she is both a princess and a little girl with a wonderful imagination. I remember being just fascinated that she’s drawn wearing a lovely dress and SNEAKERS! This meant everything to me as a child and was the perfect example of what your imagination could accomplish.

What I can’t say is what these stories might have meant for other genders, especially boys. Despite the fact that many of the characters were male, boys of the seventies and eighties were, most unfortunately, still conditioned not to like colorful, whimsical, nor magical things. Liking animals was “girly” and I remembered thinking that I had to hide my love of Unicorns lest people thing I was TOO girly (I was, after all, a self-proclaimed tomboy). But something struck me as a very deliberate choice on Cosgrove’s part when he named his male sheep “Yew,” which, to a child first learning to read, would likely have been nearly indistinguishable from “Ewe”. It may be that there is nothing to this theory at all, but I like to believe that Cosgrove was deliberately trying to subvert gender roles. Considering the often VERY progressive morals that he included in the Serendipity Book series, this isn’t much of a stretch.

I wish I had all 70 books and could comment on them one by one for you, but alas my collection has been much reduced from when I was a child (at least the ones I have, I imagine my mother has many more), but I kept every single Unicorn story (the previously mentioned Morgan) along with my much loved copy of Flutterby. When my own children were little, these were some of their favorites and now that I have young nieces, they continue to provide magic to my life. Not bad for a series of books that, in 1985 (the edition which many of my copies were from), were selling for $1.95. But then I suppose that’s the beauty of fables, their lessons last well beyond their day. If you have or know any little ones, keep your eyes out for the books in this wonderful series, because I have a feeling they’ll be just as cherished as mine.

Serendipity Books

Written by Stephen Cosgrove and illustrated by Robin James

Originally published in 1974