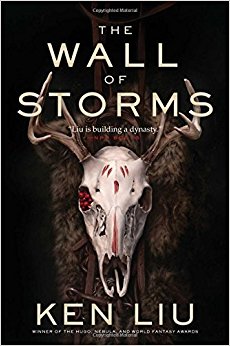

The second volume in Ken Liu’s Dandelion Dynasty series just had its paperback release, so this felt like a good moment to review this sequel to 2015’s The Grace of Kings. If you aren’t familiar with that start to the series, you can find my review of it here, and I would not recommend starting with the sequel or reading further in this review. The plot of The Wall of Storms actually does stand rather well on its own. However, the framework of Liu’s Chinese-history inspired archipelago kingdom/culture is built in the first book and could be harder to appreciate or grasp without starting there.

As hefty and epic a tome as its predecessor, The Wall of Storms seems to fit in the overall series plot arc as a transition. As meaningful and impactful as Liu’s debut novel, the sequel continues similar themes of individual and societal struggles to advance and improve, but within a political context shifted from revolt to one of maintaining benevolent power amid threats internal and external. A split between those internal to external threats comprises a hinge both conceptual and physical: forming the transition from events in The Grace of Kings to those to come in the third volume, and dividing The Wall of Storms into roughly equal halves. The novel deals with the ramifications of Kuni Garu’s populist rise to power as Emperor Ragin of Dara, with the consequences of the actions and compromises that he, and other characters, made while seeking the greater good or in yielding to their weaknesses.

Though proven masterful as an inspiring revolutionary and as a brazen military tactician, Kuni now faces the trials of governance, of maintaining a vast empire and forging progress and cultural changes that some may not welcome. Compounding Kuni’s challenges, political intrigue within Dara’s various levels of power intersects his personal life through the rivalry between his two wives and the uneven temperaments of his children. As internal machinations and squabbles come to a head, a surprising new threat lands on Dara’s shores, wedging the royal family further apart. Facing conquest by the brutal invading Lyucu culture and their devastating flying beasts of war, it is up to Emperor Ragin’s children to find a way to save Dara and preserve the newly formed dynasty.

The catastrophic arrival of the invading Lyucu tips Dara into utter chaos: a metaphorical wall of storm that hits halfway through the novel like a tsunami. The many pages leading up to this plot point that is featured on the back cover of the book are no means dull or wasted, but dominated by foreboding winds of court intrigue that focus on a new character, Zomi Kidosu. An intelligent and creative young scholar, Zomi arrives at court for the Imperial Examinations, proposing technological and societal changes that equally evoke excited wonder and fear. Through chapters that alternate between present and past, Liu provides Zomi’s backstory: a poor girl from a fishing village whose potential is discovered and trained in secret by Luan Zya, the scholar who formerly served as Kuni’s advisor.

Zomi is the first of two new female characters to dominate The Wall of Storms. (The second is Princess Thera, who technically is not new, but only a baby in the previous novel.) The Grace of Kings has its share of powerful female characters, such as Kuni’s wives (Jia and Risana) and Gin Mazoti, the military genius that brought success to Kuni’s most risky tactics. Each of these characters is back in The Wall of Storms and continues to profoundly influence events. But in place of the male leads of the first novel, the sequel leads with Zomi in the first half and with Princess Thera, Kuni’s eldest daughter, in the second half. Like the male leads in the first novel, Zomi and Thera are vividly complex characters who come to the forefront through a combination of luck, divine intervention, and their own strengths at vision and inspirational leadership. Yet they also falter in doubt and missteps.

As this younger generation of characters comes to prominence, Liu’s handling of the previous generation does begin to ‘disappoint’. Based on all that Kuni accomplished in the first book, he comes across as too unbelievably impotent and inactive – even oblivious – in The Wall of Storms. For the other older characters, the ‘disappointment’ was more in the personally emotional sense than in the sense of being a criticism of Liu. Jia becomes increasingly unlikable and selfishly cruel, despite her arguments of doing things for the greater good. This adds great realism, going against expectations, but it then also can’t help but be a letdown to what a reader envisions or hopes she could be. Even Gin, perhaps my most favorite character, is cast down from power to make way for the rise of the newer generation. I found this decline of beloved characters to be more heartbreaking than any death that George R.R. Martin produces in his epic fantasy. You’ve grown to care about these characters in The Grace of Kings, to cheer for their heroism and ideals against the odds. But their time is past, and new challenges have come for the young to face.

The one older character that bears perhaps the most sorrowful and catastrophic decline is Luan. After the invasion of the Lyucu, Liu again relates the plot through chapters that alternate between the present and the past. The flashback chapters chronicle what befalls Luan after he departs his student Zomi, and sets forth on the sea to explore the unknown, into a physical wall of storms that blocks safe travel beyond. Through a mixture of brilliance, technology, and divine plans, Luan makes it past the ‘wall’ to discover the Lyucu, and the ultimate fate of the fleet sent out in the previous novel by the former Emperor Mapidiere.

As mentioned above, Liu doesn’t spend much time ‘reteaching’ readers about Dara’s culture; the richness of the first book doesn’t really leave much room to expand. However, the second half of The Wall of Storms is able to introduce and develop the Lyucu culture. The sharp cultural contrast powers the clash of the two civilizations when the Lyucu invade and Dara fumbles in response. The second half of the novel continues Liu’s method of using history as inspiration to blend with a steampunk sort of technology and mythological types of divine intercession. I continued to enjoy the way Liu’s characters (in this case now Princess Thera) rationally approach a challenge by thinking, forming hypotheses, and then testing things out for their development into a solution as quickly as possible.

With its complexities of plot and its large list of characters, it is no surprise that The Wall of Storms is well over 800 pages long. Reading it did not remotely feel tedious because of Liu’s ability to couple world-shifting conflict and action with emotions and decisions born from the hearts and minds of individual characters. Continuing from The Grace of Kings to address themes such as progress, technology, gender, class, and morality, The Wall of Storms now interrogates them from the point of view of being in political power, and through the new perspective of the Lyucu culture.

Even with its bulk and ambition, the novel does not resolve the conflict between the Lyucu and Dara, which may displease some readers. I can’t imagine not reading the next book, so the point on which Liu chooses to end this entry didn’t particularly bother me. His strong voice, compelling characters, and fascinating world make this epic fantasy at its best, something familiar yet still original. Unless you dislike the genre (or already read The Grace of Kings and didn’t care for its style) you should give this rewarding series a try and return to the depth of Dara.