“I was born mortal, and I have been immortal for a long, foolish time, and one day I will be mortal again; so I know something that a unicorn cannot know. Whatever can die is beautiful — more beautiful than a unicorn, who lives forever, and who is the most beautiful creature in the world. Do you understand me?”

“No,” she said.

The magician smiled wearily. “You will. You’re in the story with the rest of us now, and you must go with it, whether you will or no.”

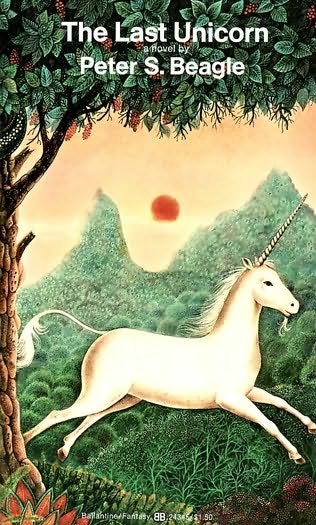

— The Last Unicorn, by Peter S. Beagle

I couldn’t have been more than 5 years old when The Last Unicorn came out on VHS and I watched it so often that my video store had to replace it within a year. My sister and I were absolutely enthralled by the delicate artistry of the unicorn, terrified of the Red Bull, and befuddled by some of the trippier moments (boob tree, anyone?). I always imagined the film to be more born of the imaginations of the production and animation studios, than of Peter S. Beagle’s writing. That is where I was woefully incorrect. This is the first time that I have ever read The Last Unicorn and, though the movie will always be my go-to, I am well and truly in love with this heartbreaking fairy tale.

Put simply, The Last Unicorn is the story of a unicorn who discovers that she is the last in all the lands and her journey to find the others and save them from King Haggard and the Red Bull. However, there is such a rich masterpiece within that summary that I feel as if I have to tell you more. The unicorn of our tale leaves her enchanted woods in search of other unicorns after two hunters reveal that she is the last one. But it isn’t until a chance encounter with a nonsensical butterfly that the unicorn learns of King Haggard’s Red Bull who drove all the unicorns to the sea. We meet Schmendrick the Magician, an itinerant wanderer with little real magic, employed at the witch Mommy Fortuna’s Midnight Carnival, after the unicorn is captured. Schmendrick frees her, and she, in turn, frees the rest of the menagerie, including the only other true creature of legend, a Harpy who kills Mommy Fortuna. The unicorn and Schmendrick later meet a band of outlaws that include an embittered Molly Grue, who joins them for the rest of their journey to King Haggard’s castle and the home of the Red Bull. Later, in escaping the Red Bull, Schmendrick transforms the unicorn into a human woman, whom they name Lady Amalthea. When they reach the castle, King Haggard hires Schmendrick to entertain him and Molly to be his cook and scullery maid. The King’s adopted son, Prince Lir, who is foretold to be the ruin of King Haggard, falls madly in love with the Lady Amalthea and she, in turn, losing more and more of her unicorn self, falls in love with him. Thus they bide their time until finding the way to the Red Bull and hopefully a way to change Lady Amalthea back into a unicorn and free the rest of her kind.

It is interesting to note that much of the story functions as a fairy tale within a fairy tale, but it’s hard to tell quite when this begins. It’s not when the unicorn sets out from her woods, nor when she meets Schmendrick, or even Molly, though both play important roles in the story. It’s as if two places exist out of time and thus are subject to the rules of the fairy tale — the first is the unicorn’s wood, a place which knows no death and is forever in a state of spring; the second is King Haggard’s kingdom, which has been dying since he came to it and feels as if it’s in a perpetual state of winter. Time only passes in-between, or rather, as the unicorn feels, “it was she who passed through time as she traveled. The colors of the trees changed, and the animals along the way grew heavy coats and lost them again” (p7). Time and the way it functions come up repeatedly through the book, but I have yet to draw any sort of master conclusion from this revelation. Particularly as it relates to the concept of a fairy tale. But, as I was saying, it isn’t until the unicorn, Schmendrick, and Molly reach the town of Hagsgate (notably missing from the movie) that you get a real idea that greater laws than physics are at work on the story.

Hagsgate, and King Haggard’s castle, are bound together by a curse which foretells that Hagsgate shall prosper until King Haggard’s castle falls, and the castle will fall when someone from Hagsgate causes it. So though the town prospers, it is joyless for knowing that their doom is inevitable and doubly joyless because they HAVE NO CHILDREN in an effort to subvert the curse. Hagsgate seems to epitomize the dark side of a unicorn’s immortality, the stagnation that comes from no birth, no change. They are locked in time, trapped by their fear of King Haggard, but also their fear that they will cause his doom. It’s an absolutely fascinating addition. But the curse that they live under is also what gives rise to the “hero” of the fairy tale, none other than Prince Lir. However, Beagle isn’t writing a typical fairy tale. He demands you look at it as such, but then subverts the rules. Our hero, after all, will destroy Haggard, but also destroy the people whom he is presumably supposed to be saving.

For me, the most powerful scene in the movie and the book is the moment when Molly first meets the unicorn. “Damn you, where have you been?” she cries, “Where were you twenty years ago, ten years ago? how dare you, how dare you come to me now, when I am this?” (p83) while indicating her own body as if it is shriveled, soiled, and unworthy of a unicorn. Since we all know that unicorns are only meant for virgins, this is a decidedly shocking moment for a children’s book (as is the gruesome death of Mommy Fortuna, truth be told). But it’s also perhaps the most emotional moment. Soon after, Molly gives us even more insight into both herself and, more importantly, being human, “It’s the princesses who have no time… The sky spins and drags everything along with it… but you stand still. You never see anything just once. I wish you could be a princess for a little while… Something that can’t wait” (p89).

It is this idea that really seems to effect the unicorn as human: Lady Amalthea is forced to experience the passage of time, the loss of herself, and eventually the concept of regret. But she can’t defeat the Red Bull until she experiences the preciousness of love, a thing which seems to need time to exist. For, after all, what is love if there is no concept of loss? And can you lose something if another thing will be there tomorrow and the day after for all eternity? The unicorn cannot fight the Red Bull the first time she faces him, because she loses nothing even in losing (not even her life, for his intent is not to kill). It isn’t until she falls in love with Lir and then loses him that she can fight because she finally has something to fight for. And this is where I think most people get The Last Unicorn wrong. Lir is NOT the hero of The Last Unicorn. He might be the “hero” of countless fairy tales within the book, but I think arguments can be made for Schmendrick and Molly as well. However, it is really the unicorn that is the hero of her own story; she just requires a bit of help along the way.

There are a lot of layers in The Last Unicorn, from the concept of time and how it affects our humanity, to the dismantling and reassembly of fairy tales, from the idea that magic is all around us, to a fascinating reading of Lady Amalthea, Molly Grue, and Mommy Fortuna as a sort of maiden, mother and crone dialectic that I am frankly not quite capable of exploring. I haven’t even touched on King Haggard, who is such a sad, dismal thing that it’s hard to feel anything but pity for him, and have barely mentioned Mommy Fortuna, similarly conquered by her own need to control power. Will a child get any of the finer points? I somewhat doubt it. I honestly did just view it as a fairy tale when I was a kid. But the threads are all there in the book, just waiting to be teased out by a reader. I honestly can’t say what I would have gotten out of the book as a child, but what I can say is that The Last Unicorn is genuinely beautiful and everyone should take the time to read it.