Welcome to the latest installment of my comics review column here at Skiffy & Fanty! Every month, I use this space to shine a spotlight on SF&F comics (print comics, graphic novels, and webcomics) that I believe deserve more attention from SF&F readers.

This month, I’d like to direct your attention to the anthology Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection Volume 2. (This review contains spoilers!)

Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection Volume 2

Contributors: Alexandria Neonakis, Alina Pete, Armand Garnet Ruffo, Daniel Heath Justice, Darcie Little Badger, David Alexander Robertson, David Cutler, David Mack, Elizabeth LaPensée Ph.D, Fred Pashe, Gerard and Peta-Gay Roberts, Haiwei Hou, James Leask, Jeffrey Veregge, Kim Hunter, Menton3, Michael Sheyahshe, Natasha Alterici, Nicholas Burns, Peter Dawes, Richard Pace, Richard Van Camp, Rossi Gifford, Scott Henderson, Sean and Rachel Qitsualik-Tinsley, Stephen Gladue, Steve Keewatin Sanderson, Tanya Tagaq, Trudi Castle, Weshoyot Alvitre

Editor: Hope Nicholson

Published by AH Comics

I would like to acknowledge that Toronto, and the land it now occupies, where I live and work, has been a site of human activity for 15,000 years. This land is the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat and Petun First Nations, the Seneca, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. The territory was the subject of the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Iroquois Confederacy and Confederacy of the Ojibwe and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes. This territory is also covered by the Upper Canada Treaties. Today, the meeting place of Toronto is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island. I am grateful to have the opportunity to live and work in the community of Toronto, on this territory.

The first volume of Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection was ground-breaking and a significant creative and commercial success. This second volume continues to build upon those successes, following another successful Kickstarter for this new collection of comics by Indigenous creators.

Every story in this volume was written by an Indigenous author; many of the artists are also Indigenous. Each story is based on a story, tradition, or teaching from the writer’s tribe or community. The goal is to highlight that “…Indigenous culture is not in the historical record. It is here, now.”

A collection that so profoundly centers Indigenous people and culture would be a dishonest one if it didn’t take note of the many significant challenges facing Indigenous people today — the legacies of colonization, oppression and genocide, in both Canada and the United States. This volume doesn’t shy away from acknowledging those challenges. Individual stories deal, directly or metaphorically, with suicide, missing and murdered Indigenous woman, and the environmental devastation of traditional Indigenous land and territory among other subjects.

But that makes the book sound like a grim slog, and it’s anything but that. Moonshot Volume 2 is a celebration of Indigenous people, of strength, resilience and the value of Indigenous lives, learning and ways of knowing. Some of the stories are sad, some are upbeat, some are very funny and all succeed in centering Indigenous people and real, vivid, living Indigenous cultures.

Some of the stories in Moonshot Volume 2 fit clearly within genre; others clearly don’t. Others are difficult for me to classify. That’s partly because in some cases, I don’t know where real Indigenous traditions and religious beliefs end and artistic license begins. But it also reflects an impressive willingness to engage with and employ ambiguity in narratives and in the interplay between text and image.

These more liminal pieces are particularly interesting to me; the North American comics tradition, especially, has a strong thread of concretizing the metaphor, an approach that genre readers will be highly familiar with. The power of comics to express ambiguity is less frequently explored.

‘They Who Walk As Lightning’ (story by Elizabeth LaPensée, Ph.D, art by Richard Pace), the story that opens this volume, captures that ambiguity beautifully. A young woman returning home to her First Nation near the heavily-polluting chemical industries of Sarnia, Ontario, finds strength in her people’s roles as water protectors, and in the the image and idea of the Thunderbird that recurs throughout. Strong art from Pace and an ease with dialogue and dramatized action from LaPensée work together to create one of the strongest pieces in the collection.

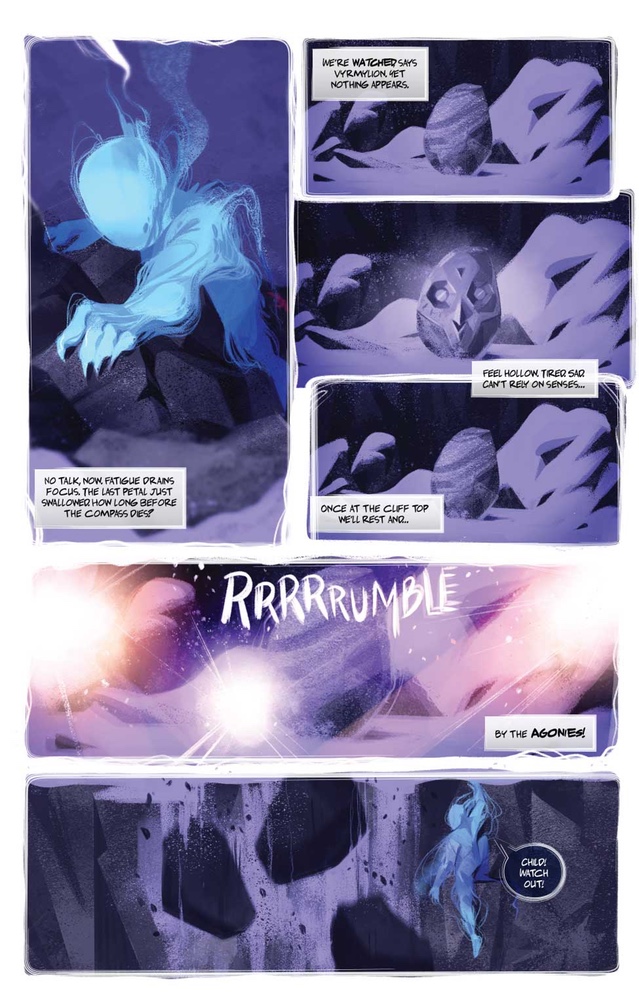

‘Winter’s Shell’ (story by Sean and Rachel Qinsulak-Tinsley, art by Alexandria Neonakis) is another powerful entry, and entirely different from the preceding story in tone and subject matter. Rooted, as the story’s introduction notes, in Inuit symbols and cosmogony, it’s a dense, rich science fantasy of an imagined Arctic (whether future or other isn’t clear) and a father and daughter on a quest for an artifact that will change the world. I want an entire graphic novel to follow up on this challenging, evocative piece.

‘Worst Bargain in Town’ (story by Darcie Little Badger, art by Rossi Gifford) draws on Lipan Apache traditional narratives for a light, funny, contemporary story that will scratch urban fantasy itches. The art is perhaps a bit weaker than the writing; a color palette that I suspect was an attempt by the artist to capture the intense natural light of the story’s Texas setting unfortunately makes everything feel washed out and not entirely solid.

‘Ka’Tephwa: Who Calls?’ (story by Alina Pete, art by Trudi Castle) marks a dramatic shift in tone and another example of narrative ambiguity with a story that uses a Cree tale to illustrate the pain of a grieving boyfriend whose partner is a missing Indigenous woman. The straightforward but profound connection between a traditional narrative of a lost love and the reality of one is heartfelt and powerful.

‘Bookmark’ (story by David Alexander Robertson, art by Natasha Alterici) is another story of grief and grieving, as a grandfather tries to help his grandson, bereaved after the suicide of a close friend, find meaning, resilience, and a way forward. Like the story it follows, it’s strongly rooted in the reality of the crises that many Indigenous people face, and a viscerally expressed pain. Alterici’s art is fits the understated writing well, and is evocative of the deep and intense emotions at play, in a story that is in the end about two people talking their way through pain, rather than dramatic action. This one was so real that it was hard to read, but I’m glad I did.

‘The Awakening’ (story by Armand Garnet Ruffo, art by David Cutler) is a classic tale of wilderness survival and a man whose life has gone wrong getting a chance to make it right. Both writing and art are capable but the piece overall has a TV movie feel; not bad, but it suffers from being in outstanding company.

‘The Magic of Wolverines’ (story by Richard Van Camp, art by Scott Henderson) is a short piece inspired by the importance of the titular animal to Indigenous people across North America, and focuses on the traditional teaching of the author’s Tliche Dene First Nation. The ideas are wonderful, but there’s no real narrative, and the art does little more than illustrate. It’s fascinating, but is only borderline comics.

Going one step further, ‘If we acted like seagulls, then perhaps we could transform into them, screaming and soaring. We would fly home.’ (story by Tanya Tagaq, art by Stephen Gladue) isn’t comics at all. It’s prose with a single illustration. And while the piece (I don’t know whether it’s fiction or memoir or something between the two) is marvelous as prose, and while I understand why the editorial team wanted a contribution by Tagaq, a celebrated and acclaimed musician and writer, in the end I don’t feel that even excellent prose was the best fit for the collection.

‘The Boys Who Became Hummingbirds’ (story by Daniel Heath Justice, art by Weshoyot Alvitre) on the other hand, is comics. A heartfelt adaptation of a Cherokee story into what the introduction describes as a two-spirit parable, the piece is commendable but relies heavily on narration. Telling only a part of the story probably wouldn’t have achieved the same aims, but might have allowed for more dramatization through dialogue and action, which might also have enhanced the emotional stakes and payoff. Alvitre’s art is very effective, though, contrasting the vivid colors associated with love and acceptance with the muted backgrounds and setting, conveying an environment impoverished by selfishness and hatred.

‘Water Spirits’ (story by Richard Van Camp, art by Haiwei Hou) is another strong story, and interestingly, like the first story in the collection, it uses a backdrop of the very real impacts of natural resource exploitation and environmental destruction to ambiguously depict what may be a brush with the numinous.

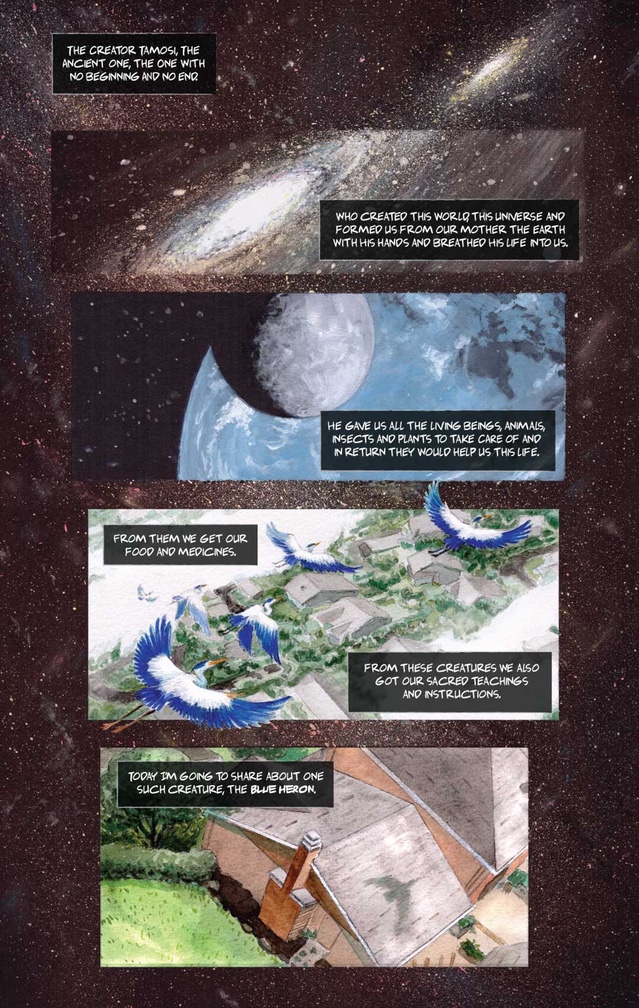

‘The Creator Tamosi’ (story by Gerard and Peta-Gay Roberts, art by Nicholas Burns) uses a Haudenosaunee creation story to frame the narrative of a man finding meaning and strength in family, community and a connection with the divine. Again, the story is told entirely through narration, and the overall effect is of a movie entirely in wide angles and voice-over, which I felt distanced me from a story that might have been even more powerful if I was allowed to get closer to the characters.

‘Where We Left Off’ (story and art by Steve Keewatin Sanderson, colors by Peter Dawes) is a post-apocalyptic story where Plains Cree people have found the resilience to survive through a return to traditional practices and knowledge. While I appreciated the ideas and the speculative elements, the action-adventure vibe of the art struck a discordant tone that seemed to celebrate the conflict the writing decried — odd, since Sanderson both wrote and illustrated this piece.

‘Do Wild Turkeys Dream of Electric Drums’ (story by Michael Sheyahshe, art by Kim Hunter) is the closest piece in the collection to being a straightforward retelling of a traditional tale, this one derived from a trickster story of the Caddo (Hasinai). While the writer attempts to use modern technology in the story to contemporize it, the device seems extraneous to the narrative and falls flat. The art, richly colored and more evocative of traditions of illustration than comics, would be excellent in another context, but does not serve this story well. It feels heavy in what should be a light story, and errs on the side of realism in a way that makes what would be comedic reversals in an oral tradition into something that reads as much more sinister.

‘Journeys’ (story and art by Jeffrey Veregge) closes the collection and is another standout piece, finding a fine balance between story and art, between narration and action and dialogue. The art, abstracted, bright and geometric, is vivid and powerful, partly by virtue of being such a stylistic departure from the rest of the volume. The story again centers the strength and resilience that come from connection to family, to elders, to traditional knowledge and teachings. It’s a powerful conclusion.

While as with any anthology, some pieces are stronger, or connected with me more directly than others, this is a broadly and highly impressive showcase of talent. These are creators who we’ll be hearing more from, in comics or other forms, in the years ahead.

“Indigenous culture is here, now.” That’s an important truth, and it’s reflected by the important truth that this book, Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection Volume 2, is here, now. Its creators are here, now.

I encourage you to give them your attention.

Disclosures: I don’t have any personal or professional relationships I’m aware of with the publisher, editor or any contributors to the anthology, unless you count that I follow some of them on Twitter. I purchased my own copy of the book.

The acknowledgement of traditional land I use at the beginning of this review was based on ones developed by the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) and by the University of Toronto’s Elders Circle (Council of Aboriginal Initiatives).

Acknowledgements of traditional land are common in discourse between Indigenous people in Canada and are increasingly used more broadly by all Canadians to encourage mindfulness and awareness of the history and present role of Indigenous people which has too often being erased from our daily lives.

0 Responses