Movie Discussion: Children of the Pines (2023)

About Children of the Pines: Daniel: Without even reading the synopsis, the title of this movie brought to my mind Children of the Corn, or something from the folk horror vein. I was a bit surprised then to find this to a be more of a psychological horror of dysfunctional family dynamics that spends more time with college-age Riley and her parents rather than the children. Aside from Riley, the adults in this movie are far more creepy than the children, particularly given that the problems of the adults are formed through their choices and desperation, rather than strictly genetic. Shaun: Surely they were aware that the casual and well-versed horror fan would make that connection with the title. And since I made the same connection, I started to think about what they had hoped to evoke in that name. Both films have a cult narrative at the core, though Pines seems to verge heavily into the new religious movement side of cults whereas Corn seems more linked to the evangelical revivalist movements. Thus, there is a modern retelling here, one linking an otherworldly spiritualism to modern psychiatry, as evidenced by the way Pines centers the adults’ narrative around what appears to be a therapy session with strange undertones and later unveils spiritual proceedings reminiscent of cult gatherings as frequently imagined in film. The psychiatry, thus, becomes the gateway to the spiritual (and, naturally, the horror). Structurally, then, this is a dramatically different film from Corn, but thematically, there are some connections that don’t seem accidental. Daniel: I’m with you on the switch here from evangelical revivalist cult to a new-age sort of cult, but the link between modern psychiatry to the supernatural consists of just using the airs of psychiatry or therapy to trap them within the cult. What was interesting to me was that the parents are never really interested in the work or change required for familial redemption or healing. They’re after an easy solution that doesn’t really require for them to change, a magical solution without the discomfort of facing problems. Actual therapy would of course be all about them actually delving into the issues and facing things. A big theme of the movie as I read it revolves around the issue of people being willing to change or not – or even the capacity for actual change. Riley at least seems somewhat open to the idea that her parents might be able to change. She decides to come home. But she quickly comes to regret this as she sees how her parents and former boyfriend are living under the power of this cult, this shared delusion that they’re going to make things better. Shaun: This is actually where I had some issues with the film. It seemed to me that this film wanted to be about quite a many number of things that it didn’t have the runtime or budget to present. The opening sequence clearly sets up a domestic violence narrative, with Riley’s father verbally abusing his family before bursting into the closet where young Riley and her mother are hiding (make no peeps…) and, we have to assume, physically attacking them. Yet, there is also a narrative here about lost loves and refusing to let go, correcting the past (or redemption), the disturbing world of cult violence and its impact on converts, and various sub-narratives around these. While I think the film’s interest in correcting the past is its most compelling story, especially when coupled with the overt domestic violence narrative at the beginning, I think it moves too far into “too much” territory when it tries to use flashbacks to show the cult at work or Gordon’s confession of love to Riley in their youth. In other words, the story gets a bit muddled, both because I lose track of what the film is trying to be about and because the film doesn’t quite stick the landing for all of the stories it is trying to tell. Daniel: Exactly! What really stuck out for me in terms of it making everything seem muddled were those scenes back to the cult, particularly with Zoe and Marie. I have to confess I still don’t quite understand their point to the overall movie or the plot. The cult flashback scenes seemed to be there to add some supernatural horror, a smattering of violence/gore that a viewer might expect from the movie. There’s no time/space to devote to the background and story here of the cult and these other girls. Sticking to the core Riley portion of the story in the present would have worked better, also because I think Kelly Tappan gives such a great performance as the character. The other characters are almost cartoonish, which can work if one wants to chew the scenes with a bit of horror campiness. Donna Rae Allen does a phenomenal job in this as Lorelei in the intro to the movie with her false smile and saccharine delivery to lure Kathy in. But Riley is the moral voice amid all the madness of everyone else in the film. Tappan gives an authority and emotion to her arguments and pleas, and she gives some really good well-articulated lines of how screwed up the familial situation is. Why that is an issue and why she needs to step out of it. On the downside, that strong performance and delivery of the script I thought contrasted harshly with other parts of the script that seemed less well written, particularly the voice-over narration given to Tappan as Riley. It comes across as cold and unfeeling, unnecessary and jarring. Shaun: I’ll admit that the voice over narrations had me rather perplexed. They were somewhat philosophical but didn’t feel grounded to the story we were there to see, especially the one that eventually unfolds. One line that stuck out to me in this regard concerned small towns and their tendency towards stagnation (same people and same buildings). On the one hand, this lines

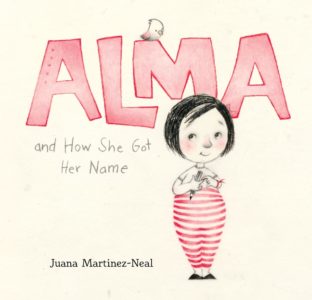

Bedtime Stories: Alma and How She Got Her Name

Bedtime Stories highlights Children’s Books with a diverse, global perspective. If you ask her, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela has way too many names: six! How did such a small person wind up with such a large name? Alma turns to Daddy for an answer and learns of Sofia, the grandmother who loved books and flowers; Esperanza, the great-grandmother who longed to travel; José, the grandfather who was an artist; and other namesakes, too. As she hears the story of her name, Alma starts to think it might be a perfect fit after all — and realizes that she will one day have her own story to tell. Alma and How She Got Her Name, from Candlewick Press, is the debut of Juana Martinez-Neal as author-illustrator and, though it isn’t my typical fairytale fare for this column, there is nothing more powerful than the telling of your own story. Alma and How She Got Her Name is an important story about both how our names have histories and how we can create our own stories. Told through almost hazy artwork in soft pinks, grays, and blues, this is a story that, though told by a father, is filtered through the eyes of a very young girl, Alma Sofia Esperanza José Pura Candela. Alma is frustrated by the fact that her name just doesn’t seem to fit. And though she seems to be talking about how it doesn’t fit on the page, her truth is that she isn’t quite sure if it fits her. Thus begins her father’s tale of the people for whom Alma was named: the grandmother who loved flowers and books, the great-grandmother who dreamed of traveling the world, the grandfather who was an artist, and more. Through these stories Alma learns who her family was and her connection to them, not just through her name, but through the things that she loves herself. I was absolutely charmed by this beautiful book and it inspired me to reminisce about my own name, and those of my children, and how they forge the connections in my own family’s story. Alma and How She Got Her Name is the perfect book to open a conversation between parents and their little ones, whether their own names are from family, friends, or perhaps a favorite book. Suitable for children ages 4-8.