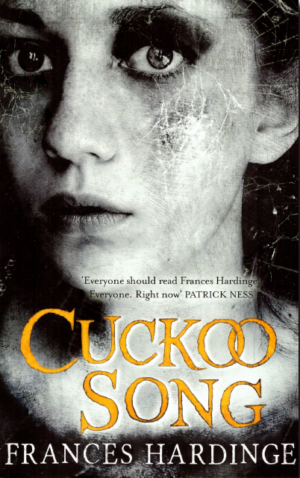

Book Review: Cuckoo Song by Frances Hardinge

It is England during the reign of King George V. The Machine Age is at its peak, and human society is in flux, becoming increasingly urbanized, secular. The Great War has come to a close, but the traumatic devastation it has wrought echoes on in family’s lives. Nations struggle to recover and political/economic turmoil presages greater conflicts and changes to come. What the future holds is not only a concern for humanity, but also for The Besiders, a race that has lived alongside us in the margins, driven further into the isolated shadows as human civilization spreads. Eleven-year-old Triss Crescent awakens in a bed surrounded by her parents and a doctor, her memory fragmented and incomplete. She gradually recalls that the family is together on vacation, and that she has had an accident, coming close to drowning in the Grimmer, a local millpond. But she has difficulty remembering the details of how she fell in, or how she managed to get out. Triss’ younger sister Pen was there to witness the accident, but Pen sulks in the corner of the room, far from Triss, and won’t say more than angrily proclaim that Triss is lying, pretending; that Triss is not who she claims to be.

Retro Nostalgia: The City of Lost Children (1995), Visual Rhetoric, and the Critic’s Confused Apparatus

May 2015 marks the 20th anniversary of the premiere of Marc Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s The City of Lost Children (1995). It is perhaps the most recognizable example of contemporary surrealist cinema, and it remains one of Caro and Jeunet’s most well-regarded works.* The surrealist nature of the film is fairly evident from even a casual viewing, as it embodies just about every layer of the film’s plot, characters, visuals, and underlying “myths.” It’s chaotic, moody, and, at times, bewildering. The City of Lost Children‘s, in other words, is not simply a fantasy; rather, it is a fantasy which has been divulged of its realistic undercurrents.