So I watched V/H/S 2 tonight. I had passed on the original, but heard that the follow-up was a distinct improvement. It was something of a mixed bag, though “Save Haven,” the segment directed by Gareth (The Raid- Redemption) Evans, was pretty effective. The film is yet another found-footage exercise, and while it finds some pretty ingenious ways of using the format (I particularly liked the dog-mounted camera), I did find myself wondering if this was really the most effective way of telling these stories. And so I present a few ramblings on found-footage horror, hoping for at least semi-coherence.

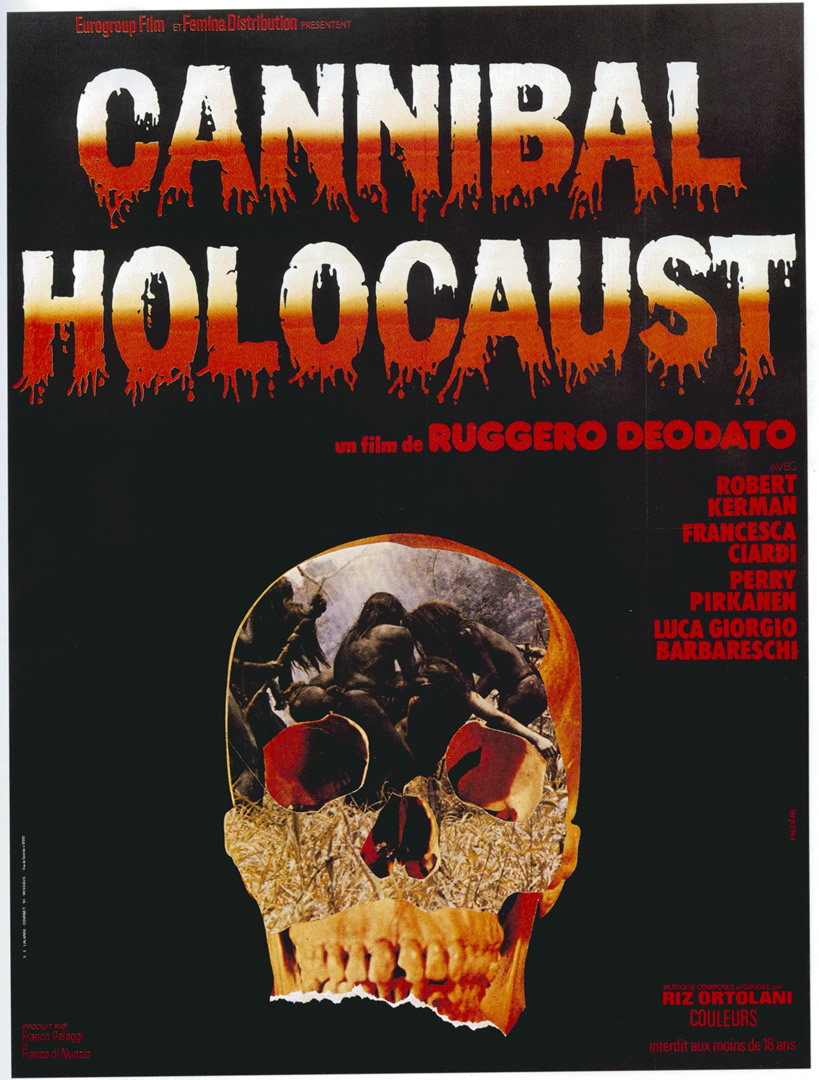

Why found footage? On the one hand, I can understand the appeal of the documentary look. But while the case might be made that it is in the aid of a greater illusion of authenticity, I don’t really buy this. To the contrary, the form draws attention to itself. It takes very little for audiences to be jolted out of the narrative as they question the contrivances on display (why on earth, for example, would our dim-witted hero choose to film his frantic search for his daughters and attempted flight at the end of Paranormal Activity 3?). And, if we look at where the found-footage horror film begins, with Cannibal Holocaust (1980), the form is very much part of the film’s point. Setting aside (perversely) the glaring problems with Ruggero Deodato’s film (as has been pointed out many times before: its apocalyptic levels of misogyny, racism, animal cruelty and a generalized reveling in the things it pretends to condemn), it is an examination of atrocities carried out in the name of art (in this case, a documentary), and so it is important to its project that the viewers be very conscious of that are watching a film. The same is true for Zak Penn’s Incident at Loch Ness (2004)*. This film is, for my money, perhaps the most effective use of footage in recent years, again because its form is integral to its point (using the language of documentaries to tell a completely preposterous story, and thus expose how easily we believe something just because of how it is told).

In short, the found footage format is most effective when it does not seek to create an illusion, but rather draws our attention to those attempts.

The same is true of a related tactic: the use of the first-person camera. In horror, this is stereotypically associated with the slasher film, but we encounter it as early as the 1931 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. As Carol Clover has argued, the problem with the idea that this technique forces identification with the killer is that, in the case of the slashers, said killers have no character with which to identify. And, once again, the effect is jolting — it forces us to become aware of the camera, rather than disappear into the narrative. In the case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, this is, again, the point. Its moments of first-person POV ask hard questions of the audience, demanding an intellectual, rather than just emotional, engagement with the drama.

But having said all this, let me end with one further observation. The found-footage approach has roots that go back much further than Cannibal Holocaust. After all, isn’t this the cinematic incarnation of literature’s found manuscripts? Melmoth the Wanderer, Frankenstein and indeed The Castle of Otranto (where the horror novel begins), to name just three, are all examples of the found manuscript. There might be some possibilities here that film has yet to explore as fully as it might.

——————————-

*Yes, this is more comedy than horror film, but it has a monster, and since horror and comedy are so intimately related, I have no qualms with including it here.